'Marsquakes' may solve 50-year-old mystery about the Red Planet

Data collected by NASA's InSight lander suggest that ancient internal processes are responsible for the "Martian dichotomy" that splits the Red Planet into two distinct halves.

Recordings of Martian earthquakes, or "marsquakes," collected by a robot on the Red Planet may have finally solved a 50-year-old mystery: why one half of Mars is so drastically different from the other.

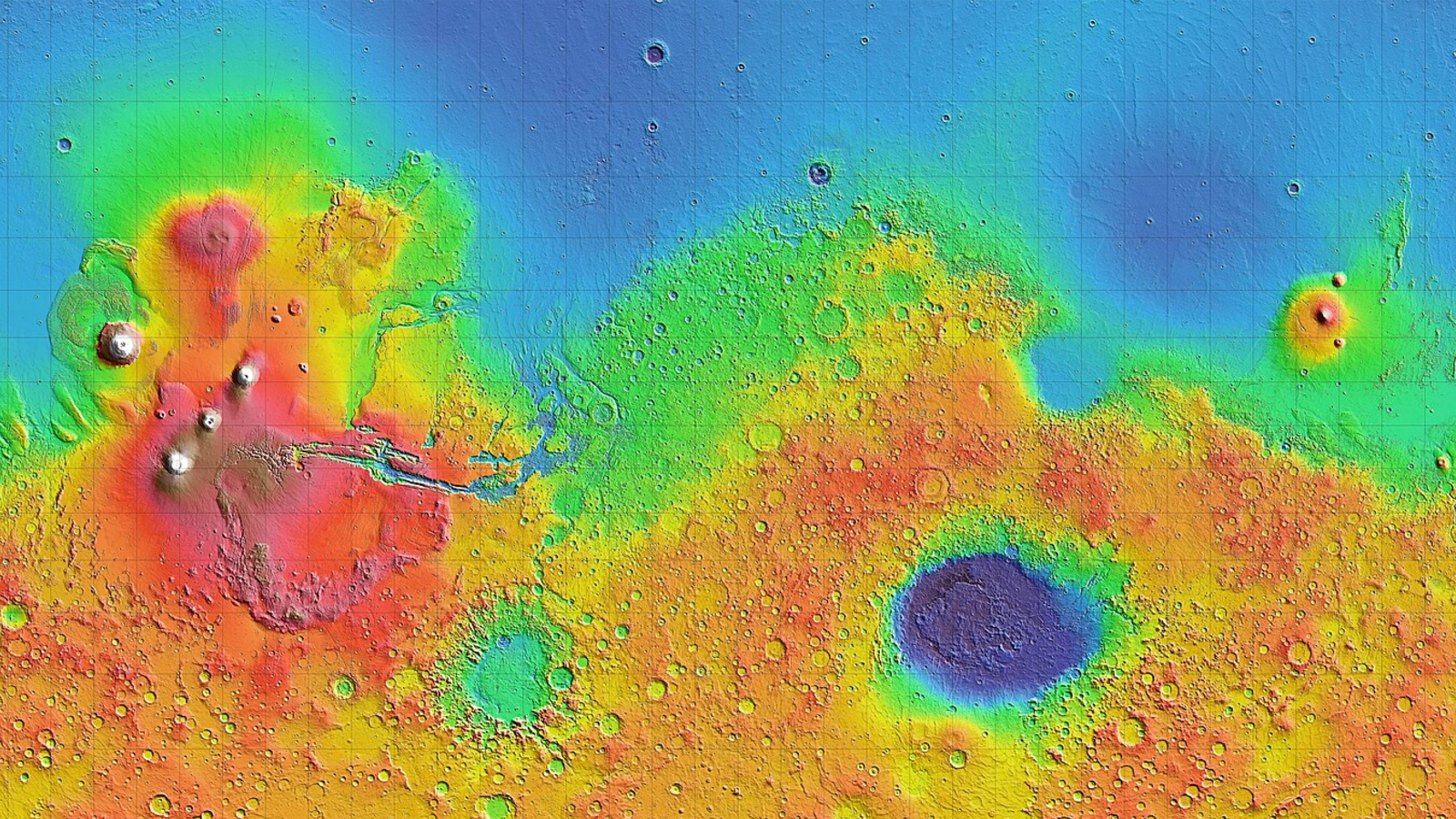

Since the 1970s, researchers have known that Mars is split into two main areas. The northern lowlands cover around two-thirds of the planet's northern hemisphere, while the southern highlands cover the rest of the planet and have an average elevation roughly 3 miles (5 kilometers) higher than that of the northern lowlands. Mars' crust, which sits on top of a mantle of molten rock similar to the one inside Earth, is also thicker in the southern highlands. This planetary imbalance is known as the "Martian dichotomy."

There are two main theories for the origin of the Martian dichotomy. One is that the divide was caused by some unknown process within the planet's interior. The other is that a massive collision with a moon-size object or multiple smaller space rocks reshaped the planet's surface. However, the ages of the rocks on the Martian surface hint that whatever caused the imbalance happened in the very early days of the solar system, which makes it hard to determine the exact cause.

But in a new study published Dec. 27, 2024, in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, researchers analyzed data from NASA's InSight lander, which records how seismic waves from marsquakes reverberate within the planet, to see if they could detect any evidence of an internal origin for the Martian dichotomy.

InSight is located near the border between the northern lowlands and the southern highlands, which allowed the team to compare how seismic waves moved through the mantle below two sites: one on each side of the divide.

"Comparing these two [sites] showed that the waves lost energy more quickly in the southern highlands," the study authors wrote in The Conversation. "The most likely explanation is that the [molten] rock beneath the southern highlands is hotter than in the north."

"This temperature difference between the two halves of the dichotomy supports the idea that the split was caused by internal forces on Mars, not some external impact," they added.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Internal origin vs. external impact

The study team thinks this temperature difference can be explained by ancient tectonic activity that has since disappeared from Mars.

"At one point, Mars had moving tectonic plates like Earth does," the researchers wrote. "The movement of these plates and the molten rock beneath them could have created something like the dichotomy, which was then frozen in place when the tectonic plates stopped moving to form what scientists call a "stagnant lid" on the planet's molten interior."

In this scenario, the magma beneath the South is constantly being pushed up against the crust, while the magma below the North is sinking toward the planet's core. This would also explain why the planet's crust is thicker in the South, the researchers added.

However, it may be too early to rule out the external impact scenario, which some recent studies have shown to be potentially viable.

"To conclusively answer the question of what caused the Martian dichotomy, we will need more marsquake data, as well as detailed models of how Mars formed," the researchers wrote. "However, our study reveals an important new piece of the puzzle."

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Harry is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. He studied Marine Biology at the University of Exeter (Penryn campus) and after graduating started his own blog site "Marine Madness," which he continues to run with other ocean enthusiasts. He is also interested in evolution, climate change, robots, space exploration, environmental conservation and anything that's been fossilized. When not at work he can be found watching sci-fi films, playing old Pokemon games or running (probably slower than he'd like).

-

Unclear Engineer The subheading on the main page is different from the subheading on the article page, and not even on the same subject.Reply

The main page subheading talks about "AI crossing a red line by cloning itself."

Perhaps "AI" is now doing the editing for Space.com? -

sooth121 Deep space nines mission is dependent upon the time traveller willing to travel through space as a subordinate-cause reflective upon the Mother Earth surfaces.Reply

For example, take a 50 year earthquake on Mars surface, since it is the first sign of discovery, it is as if on Earth we can go a generation and forget the last event until the last one that is actively pursued.

Space traveler or space chicken, I think that's a plausible assumption based on space stuff. -

COLGeek Reply

That was corrected earlier. Thank you.Unclear Engineer said:The subheading on the main page is different from the subheading on the article page, and not even on the same subject.

The main page subheading talks about "AI crossing a red line by cloning itself."

Perhaps "AI" is now doing the editing for Space.com? -

sooth121 To the un/ nuclear engineer.Reply

The data is very important for the subtopic, perhaps only Scotty can direct the AI. Until then, I can understand the command. It's about the mechanic who went through the spaceship timeline. That's it. Over and over again! Thanks, Physics Department for this outer space journey!