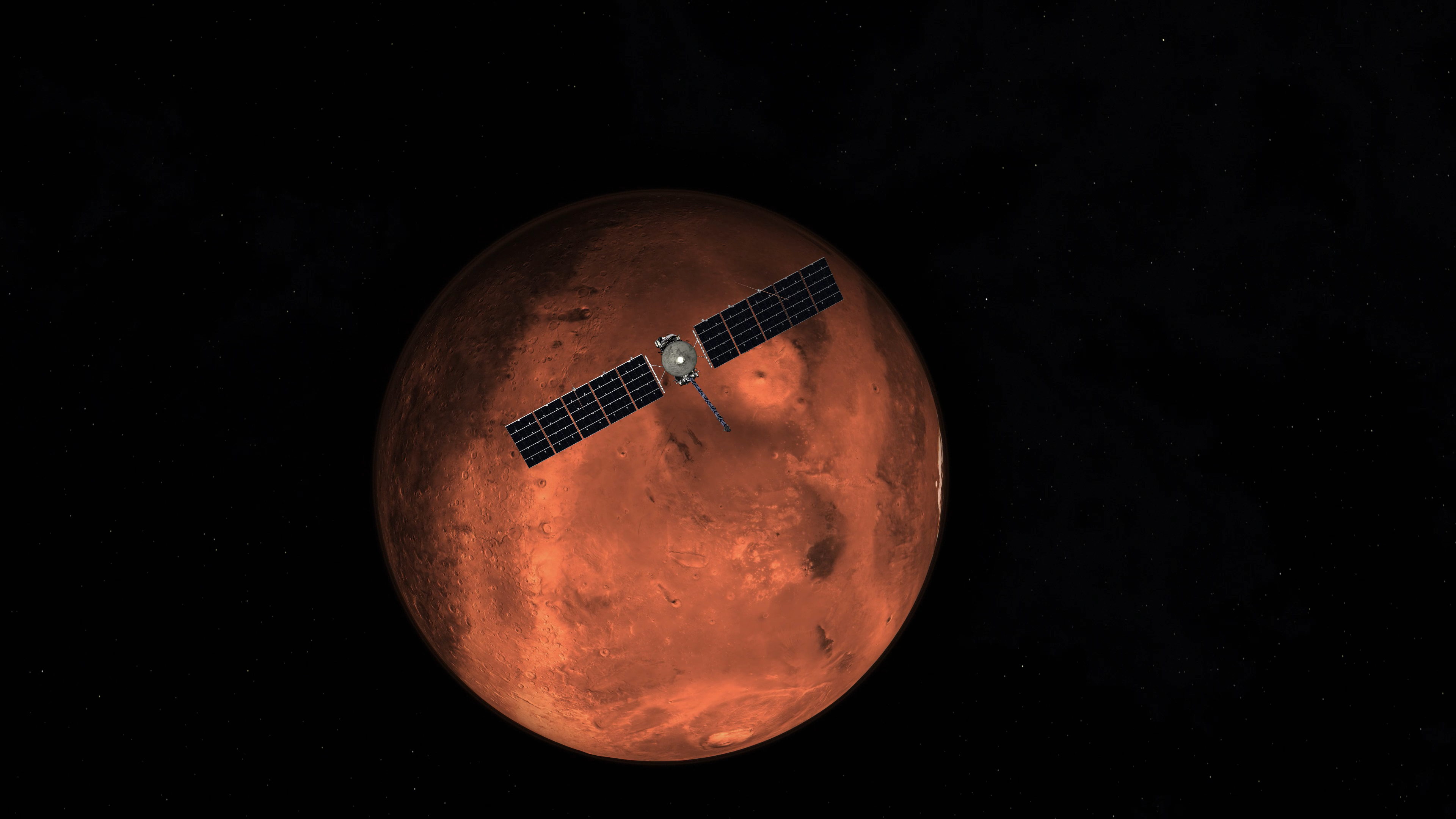

NASA's Europa Clipper will fly close to Mars today on way to Jupiter's icy moon

"It's like a game of billiards around the solar system, flying by a couple of planets at just the right angle and timing to build up the energy we need to get to Jupiter and Europa."

Today (March 1), NASA's Europa Clipper spacecraft will fly past Mars, gliding just 550 miles (884 kilometers) above the Red Planet's surface. This maneuver is designed to adjust the spacecraft's trajectory and position it for a critical phase in its 1.8-billion-mile (2.9-billion-kilometer) trek to the Jupiter system.

The probe's destination is Europa, a moon of Jupiter coated with a shell of ice that conceals a vast, presumably salty ocean. Scientists suspect the moon could have the ingredients needed for life as we know it, and the $5.2 billion Europa Clipper is NASA's first mission dedicated to gathering data that will help scientists determine whether Europa, and other ocean worlds like it, could indeed be habitable.

Europa Clipper, with its massive solar arrays, spans the length of a basketball court — making it the largest spacecraft the space agency has ever built for a planetary mission. Following its launch on Oct. 14, 2024 from NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida, the spacecraft was placed in an initial path that included some buffer room around Mars — a precaution designed to ensure any issues with the spacecraft that arose in the weeks following launch would not risk a collision with the planet.

However, Europa Clipper has operated flawlessly. So, with everything on track, mission controllers commanded Europa Clipper to approach Mars' orbit in November of last year, followed by two additional maneuvers in January and February that set the stage for today's Red Planet flyby. The meticulously planned loop around Mars will allow the spacecraft to harness the planet's gravity without expending additional propellant.

"It's like a game of billiards around the solar system, flying by a couple of planets at just the right angle and timing to build up the energy we need to get to Jupiter and Europa," Ben Bradley, Europa Clipper mission planner at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said in a statement. "Everything has to line up — the geometry of the solar system has to be just right to pull it off."

The spacecraft will reach its closest point to Mars at 12:57 p.m. EST (1757 GMT), traveling at speeds of approximately 15.2 miles per second (24.5 kilometers per second), according to the statement. Before and after this moment, the probe will harness the gravity of Mars, pump its brakes, and reshape its trajectory. Flying away from Mars, the spacecraft will clock in at about 14 miles per second (22.5 kilometers per second), the statement says.

This flyby also provides the mission team an opportunity to test two onboard scientific instruments. For one, engineers plan to turn on the spacecraft’s thermal imager and test it by capturing multicolored images of Mars.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Plus, during its closest approach, the Europa Clipper's radar instrument will also be tested to make sure it is operating as expected. The probe's radar antennas are so massive that they could not quite be tested on Earth, making this the first time all its components will be tested together, NASA said.

"We come in very fast, and the gravity from Mars acts on the spacecraft to bend its path," Brett Smith, a mission systems engineer at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, in California, said in the statement. "Meanwhile, we're exchanging a small amount of energy with the planet, so we leave on a path that will bring us back past Earth."

That flyby around Earth is scheduled for December 2026, and will position the spacecraft for a straightforward trajectory the rest of the way to its destination, with arrival at the Jupiter system planned for April 2030.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sharmila Kuthunur is a Seattle-based science journalist focusing on astronomy and space exploration. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She has earned a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social