Bullet-fast moon rocks carved 2 lunar gorges deeper than the Grand Canyon

It only took less than 10 minutes.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Two gigantic canyons on the moon — both deeper than the Grand Canyon — were carved in less than 10 minutes by floods of rocks traveling as fast as bullets, a new study finds.

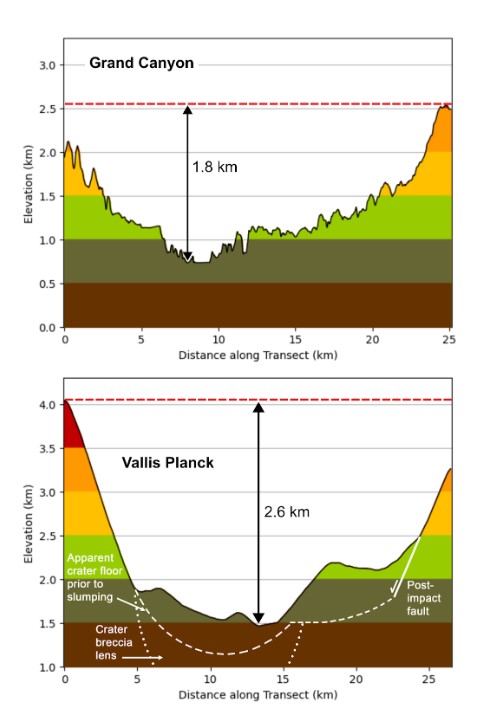

Scientists analyzed the lunar canyons, named Vallis Schrödinger and Vallis Planck, to find that these huge valleys measure 167 miles long (270 kilometers) and nearly 1.7 miles (2.7 km) deep, and 174 miles long (280 km) and nearly 2.2 miles deep (3.5 km), respectively. In comparison, the Grand Canyon is 277 miles long (446 km) and is, at most, about 1.2 miles deep (1.9 km), the researchers noted.

"The lunar landscape is dramatic," David Kring, a geologist at the Lunar and Planetary Institute of the Universities Space Research Association, told Space.com. "In the lunar south polar region, there are mountains that exceed Mt. Everest in height and canyons that exceed the Grand Canyon in depth. Future lunar surface explorers will be awed."

This pair of lunar canyons represents two of many valleys radiating out from Schrödinger basin, a crater about 200 miles wide (320 km) that was blasted out of the lunar crust by a cosmic impact about 3.81 billion years ago. This structure is located in the outer margin of the moon's largest and oldest remaining impact crater, the South Pole–Aitken basin, which measures about 1,490 miles wide (2,400 km) and dates about 4.2 billion to 4.3 billion years old.

Kring and his colleagues investigated the Schrödinger basin for potential landing sites for future robotic and human lunar missions. They analyzed photos from NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter to better understand how Vallis Schrödinger and Vallis Planck formed, generating maps from these images of the moon's surface to calculate the direction and speed of debris expelled from the collision that created Schrödinger basin.

The scientists estimate that rocky debris flew out from the impact at speeds between 2,125 to 2,860 miles per hour (3,420 to 4,600 km/h). In comparison, a bullet from a 9mm Luger handgun might fly at speeds of about 1,360 mph (2,200 km/h).

The researchers suggest the energy needed to create both of these canyons would have been more than 130 times the energy in the current global inventory of nuclear weapons.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The lunar canyons we describe are produced by streams of rock, whereas the Grand Canyon was produced by a river of water," Kring said. "The streams of rock were far more energetic than the river of water, which is why the lunar canyons were produced in minutes and the Grand Canyon produced over millions of years."

The angle at which the collision occurred led the resulting debris to scatter in an uneven manner around the Schrödinger basin, with less material covering the area closer to the South Pole–Aitken basin. With less debris covering this ancient region, astronauts that land there "will find it easier to collect samples from the earliest epoch of the moon," Kring said.

The scientists detailed their findings in a paper published on Feb. 4 in the journal Nature Communications.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us