How did Earth get such a strange moon? Exploring the giant impact theory

Surprisingly enough, the moon is a piece of our planet.

The moon is weird. It's completely unlike anything else in the solar system. So how did our planet end up with such a special moon? The answer is that, surprisingly enough, the moon is a piece of our planet.

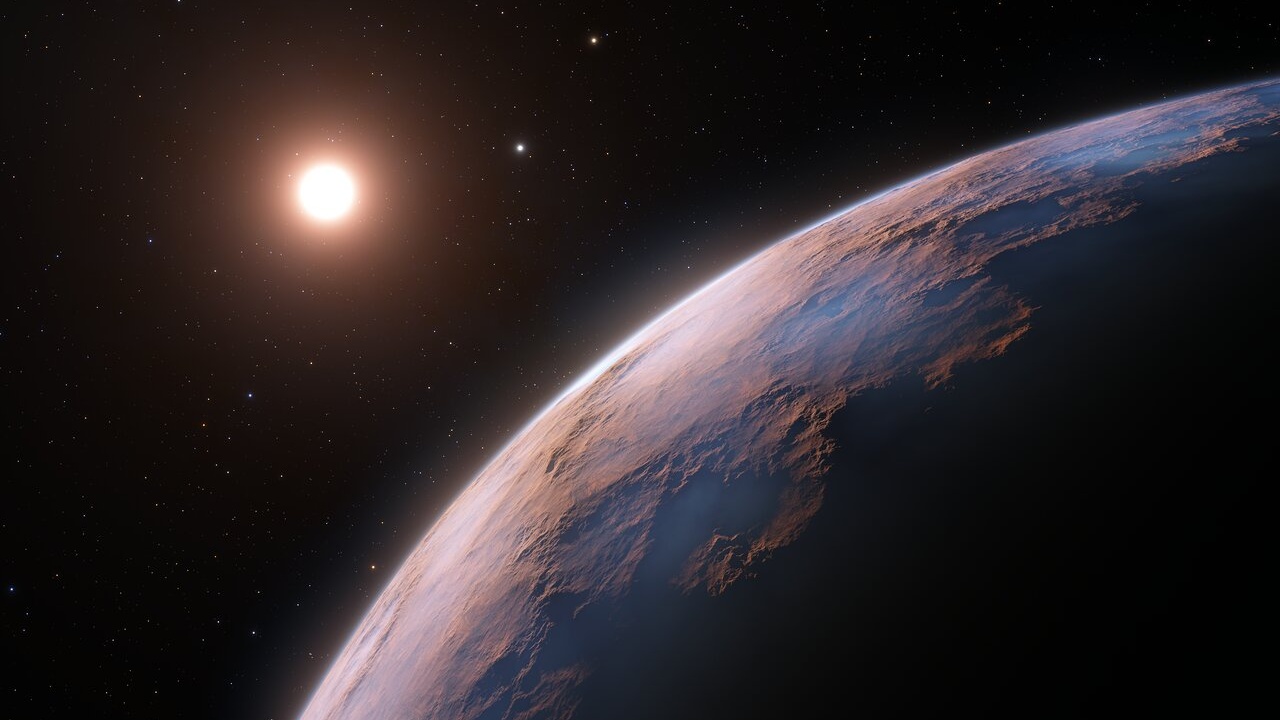

There's a lot going on with the moon. For starters, it exists, which is weird in its own way. Mercury has no moons, and neither does Venus. Mars does have two moons, but they're really just captured asteroids. Earth is the only rocky planet in the solar system with a significant moon.

And the moon really is significant: It's roughly 1.2% the mass of Earth. That may not be big in an absolute sense, but for the solar system, that's huge. No other moon is that large relative to its parent planet.

The oddities don't stop there. The total angular momentum of Earth's spin, the moon's spin and the moon's orbit is very large — far higher than for any other terrestrial planet. So how did we get so much momentum?

Plus, the moon is full of "KREEPs" – that is, potassium (K), rare-Earth elements (REE) and phosphorus (P). These elements don't usually like to hang out together, but lunar samples show that they are often mixed. That requires the moon to have been molten at some point, which takes a lot of energy.

And the real icing on the cake is that the moon has many of the same abundances of stable isotopes as Earth does, which indicates that Earth and the moon evolved from the same clump of material.

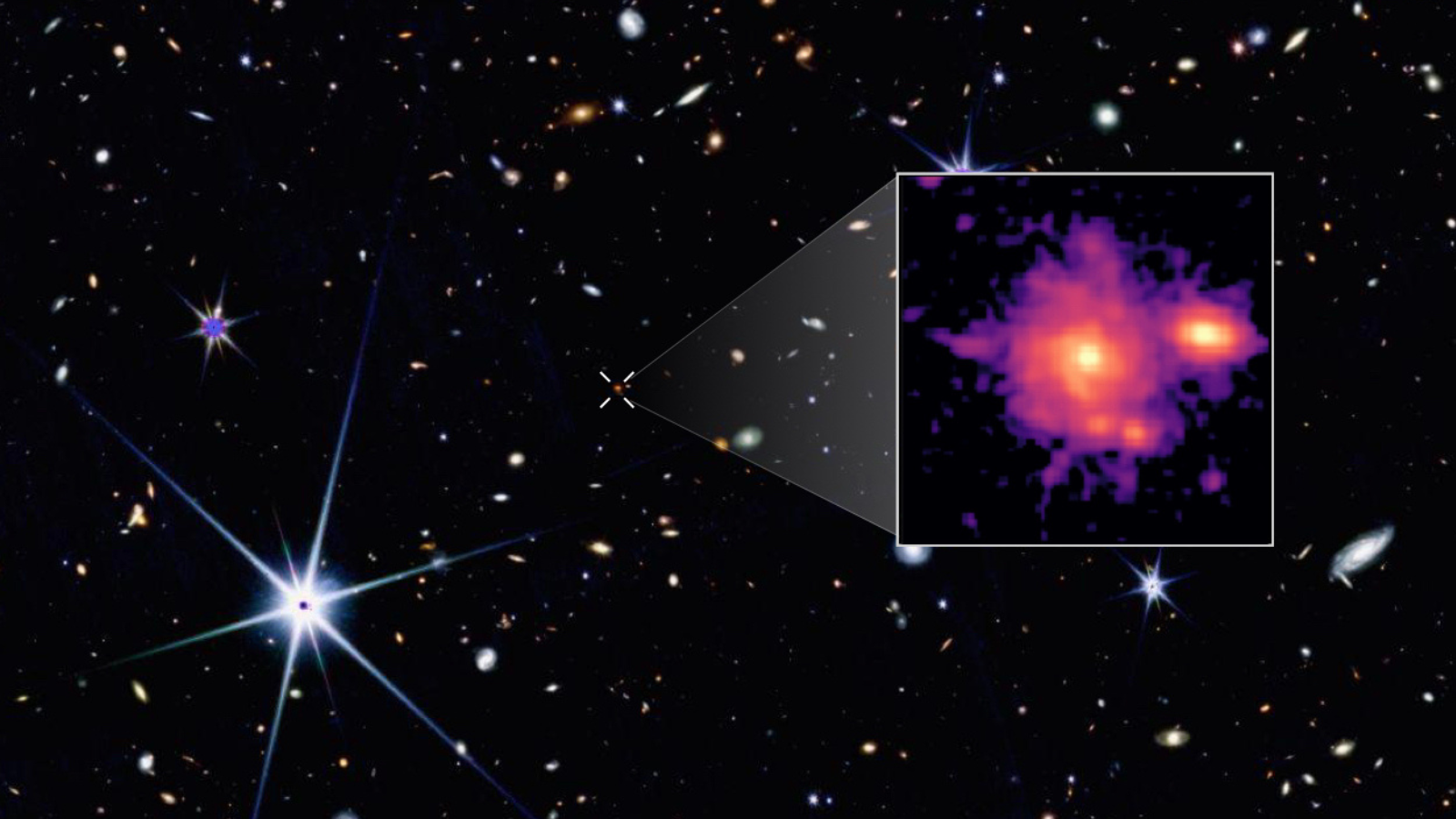

The leading explanation for all of these mysteries is known as the giant impact hypothesis. According to this story, when the solar system was just getting started, a Mars-size protoplanet named Theia slammed into the proto-Earth.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

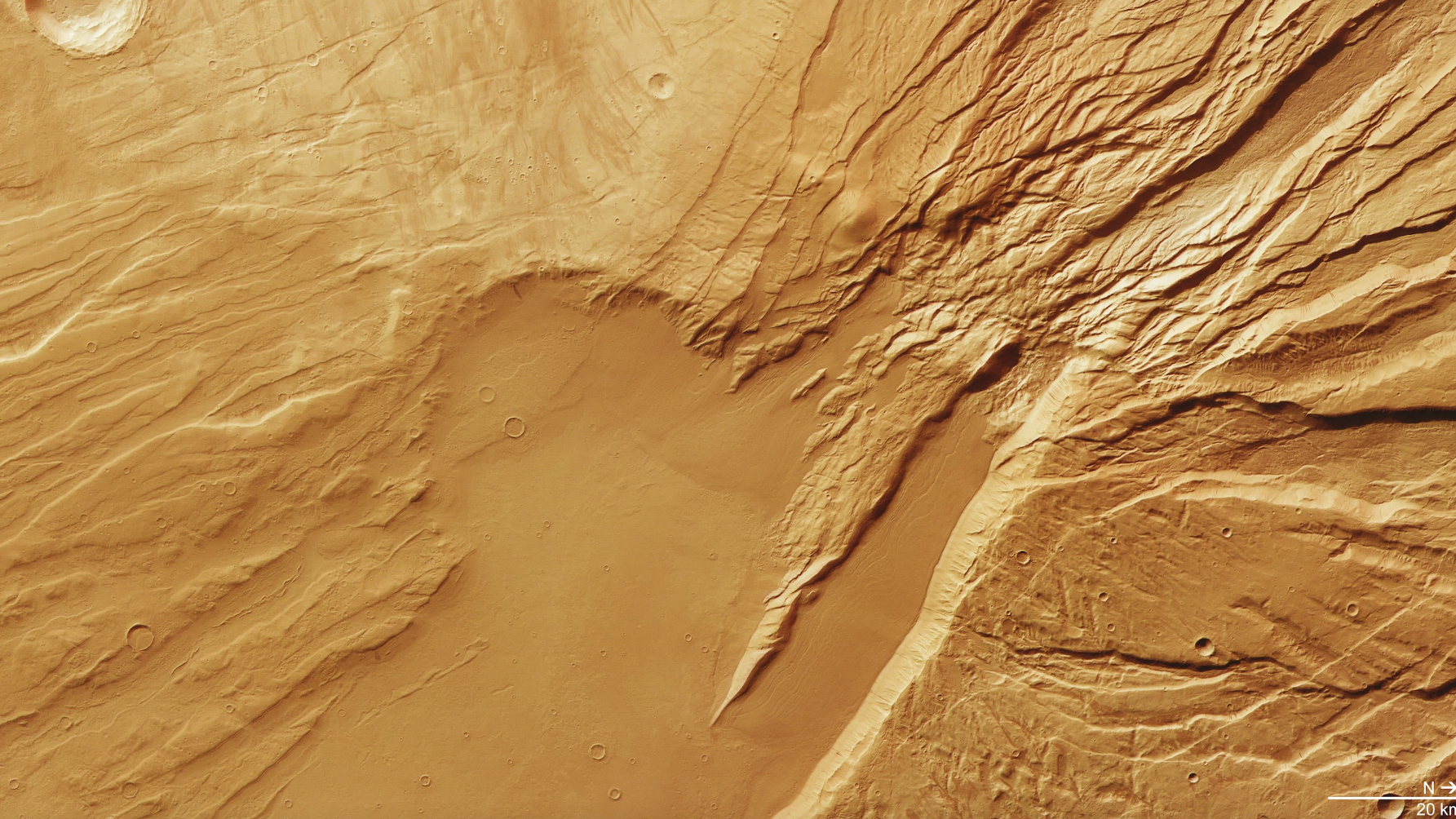

With an impact velocity of somewhere around 20,000 mph (32,000 km/h) — relatively slow as impacts go — what happened next was nothing short of catastrophic. The heavy core of Theia sank deep into Earth, enlarging our planet's core. The two bodies' mantles mixed and thus bulked up our planet. And the crusts were scattered far into space.

What happened next is a little hard to follow and depends a lot on exactly how the impact unfolded and what Theia was made of. But the general picture is that some stuff went flying away, never to return. Other stuff rained onto Earth's surface. And a big chunk remained in orbit. In as little as a few hours — or perhaps up to a century or more — that material coalesced into its own solid object: the moon.

Some models suggest that a second moon, just a few hundred kilometers across, formed past the far side and then slowly approached the moon and pancaked itself. This would explain why the far side of the moon is lumpier than the near side.

There's also the possibility that this wasn't a low-energy, glancing blow at all — that instead, the proto-Earth was spinning really quickly and then got nailed by Theia. This would have delivered more than enough energy to vaporize everything and create a doughnut-shaped ring of plasma known as a synestia.

No matter what, this impact released a lot of energy — more than enough to turn the moon into a molten ball, more than enough to bring the KREEP elements together, and more than enough to mix Earth's original material and Theia's to create a set of common features between Earth's crust and the moon.

As with all hypotheses, it's not perfect. For example, if there's enough energy to liquefy the moon, there's enough energy to liquefy Earth's surface. But there is no evidence for large-scale magma seas in Earth's history. Also, the moon does have some volatile elements, like water, trapped in rock — but a giant-impact, giant-energy event should have gotten rid of those.

Despite those caveats, the giant impact hypothesis is the most compelling story we have for how the moon formed. And without a time machine into our distant past, we'll never be able to prove it. But it still fits almost all of the evidence we have so far, so it's a story worth keeping around.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Paul M. Sutter is an astrophysicist at SUNY Stony Brook and the Flatiron Institute in New York City. Paul received his PhD in Physics from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 2011, and spent three years at the Paris Institute of Astrophysics, followed by a research fellowship in Trieste, Italy, His research focuses on many diverse topics, from the emptiest regions of the universe to the earliest moments of the Big Bang to the hunt for the first stars. As an "Agent to the Stars," Paul has passionately engaged the public in science outreach for several years. He is the host of the popular "Ask a Spaceman!" podcast, author of "Your Place in the Universe" and "How to Die in Space" and he frequently appears on TV — including on The Weather Channel, for which he serves as Official Space Specialist.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.