New cosmic 'baby pictures' reveal our universe taking its 1st steps towards stars and galaxies

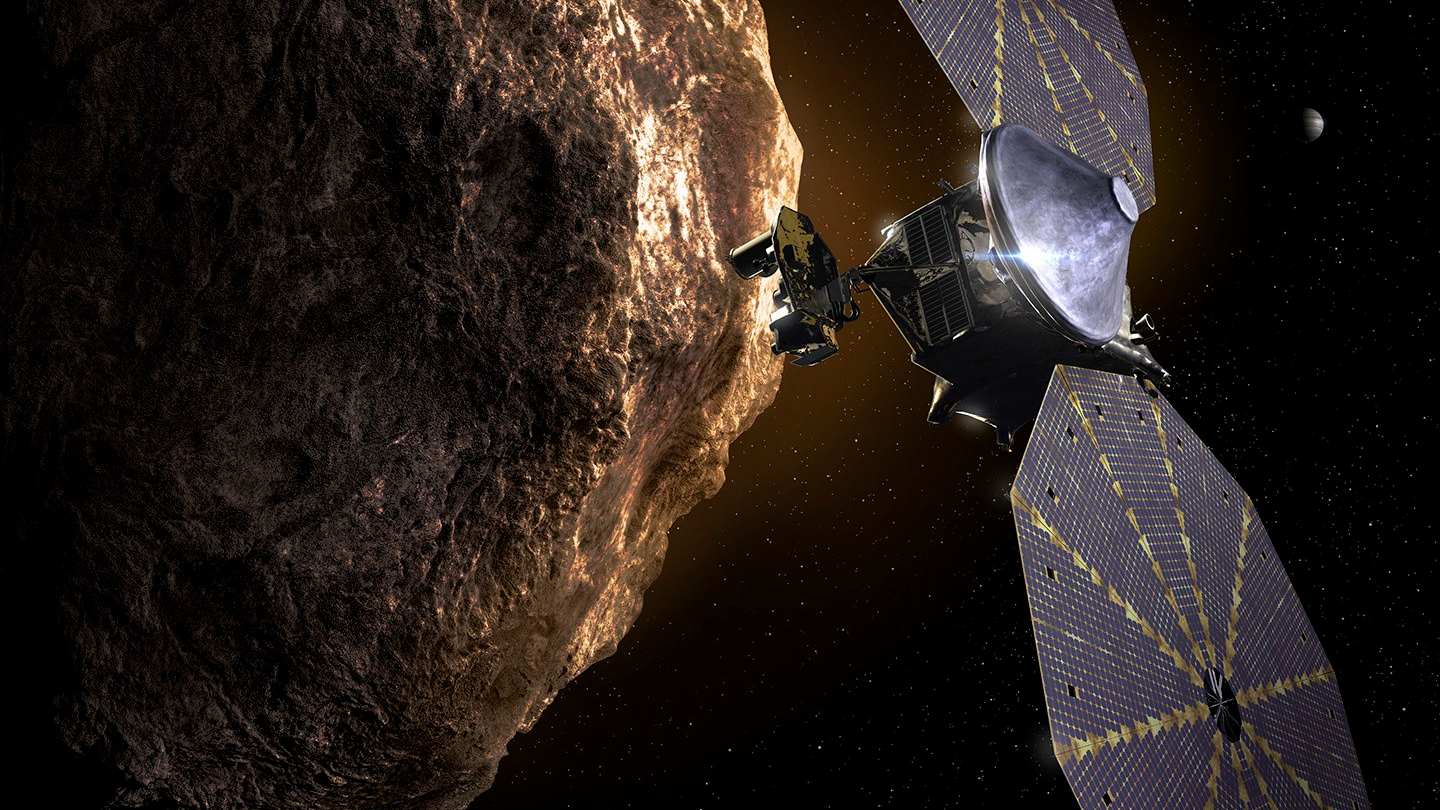

The new images come from the now-retired Atacama Cosmology Telescope which shuttered its cosmic eye in 2022.

New images of the infant universe captured by the Atacama Cosmology Telescope (ACT) are the most precise "baby pictures" to date of the cosmos' "first steps" toward forming the first stars and galaxies.

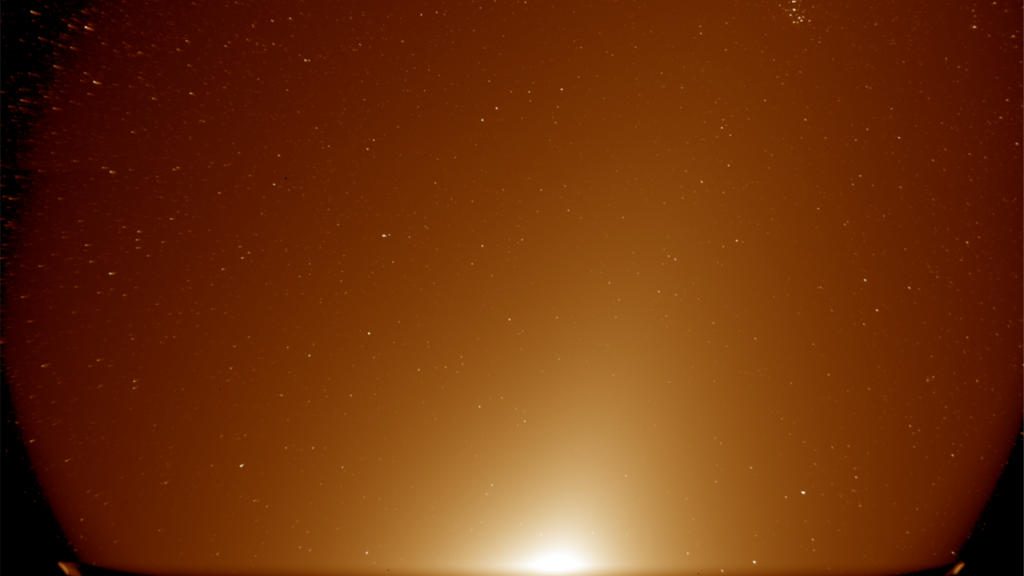

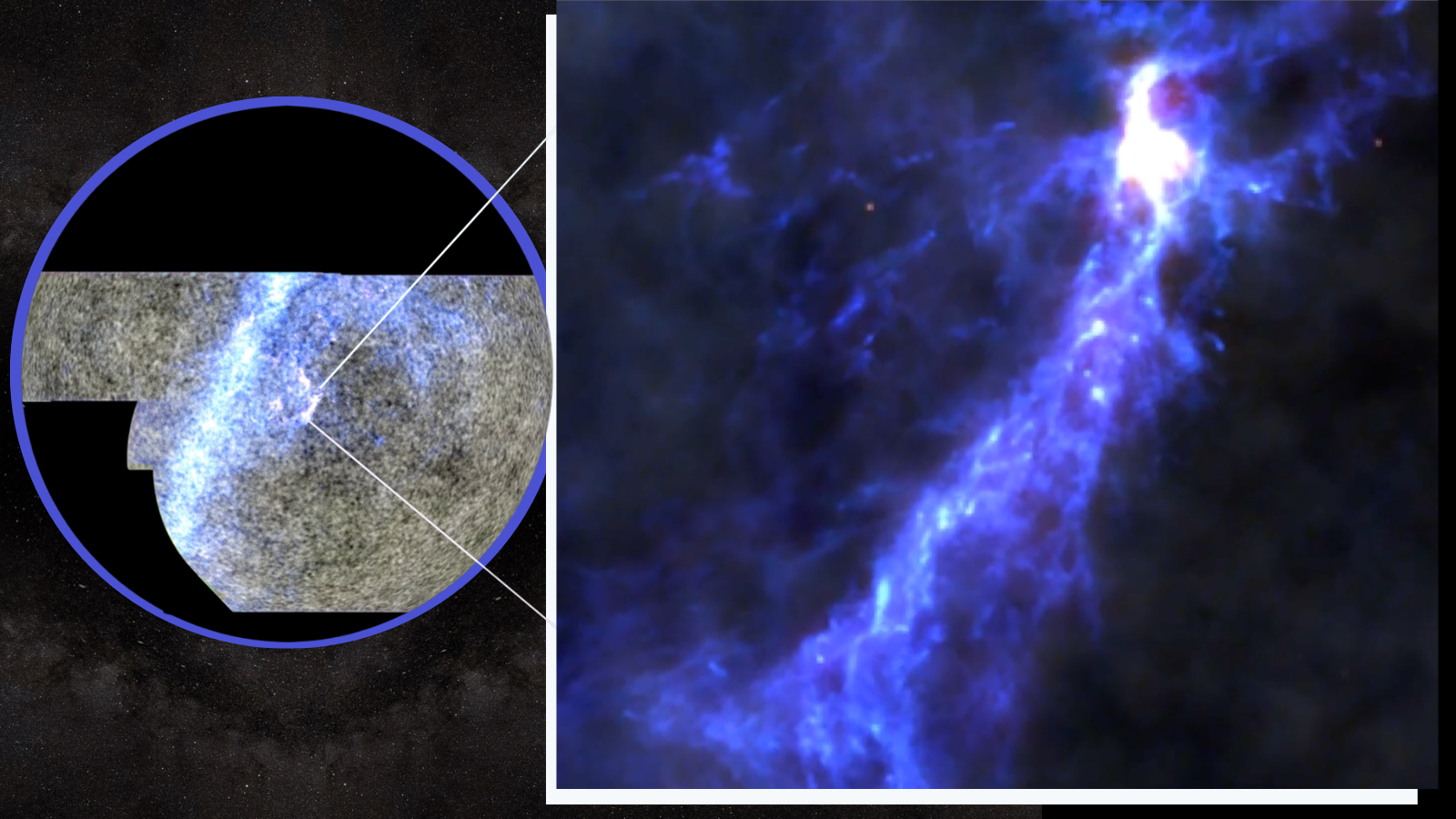

The images of the cosmic microwave background (CMB), which is a fossil relic of the first light in the universe, reveal what the 13.8 billion-year-old cosmos was like just 380,000 years after the Big Bang.

This incredible achievement from ACT has helped scientists validate the standard model of cosmology, the best description we have of the formation and evolution of the universe. In addition to showing this model to be incredibly robust, the ACT images show the intensity and polarization of the earliest light with unprecedented clarity.

The new data from ACT revealed the motion of the ancient gases in the universe as they are pulled by gravity. This shows the formation of ancient clouds of hydrogen and helium that will later collapse to birth the first stars. Thus, this constitutes the universe taking its first step towards the formation of galaxies.

"We are seeing the first steps towards making the earliest stars and galaxies," director of ACT and Princeton University researcher Suzanne Staggs said in a statement. "And we're not just seeing light and dark; we're seeing the polarization of light in high resolution. That is a determining factor distinguishing ACT from Planck and other earlier telescopes."

Despite telling scientists a great deal about the conditions in the early universe, these new ACT findings didn't contain clues that could help solve one of the biggest problems with our understanding of cosmic evolution: the so-called "Hubble tension."

Baby's first light

Prior to around 380,000 years after the Big Bang, the universe was a dark place, quite literally. That is because the cosmos was so hot and dense at this time that it was filled with a sea of plasma packed with unbound electrons that endlessly scattered photons, the particles that comprise light. This meant that light couldn't travel through the cosmos unimpeded, and thus, the cosmos was opaque like a dense fog.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once the universe expanded and cooled enough (down to around 3000 Kelvin (approximately 4,900 degrees Fahrenheit or 2,700 degrees Celsius), electrons were able to bind with protons and form the first neutral atoms of hydrogen and helium, the first elements. This meant that photons suddenly were no longer endlessly scattered and were free to travel. Suddenly, after this event called the "last scattering," the universe was transparent.

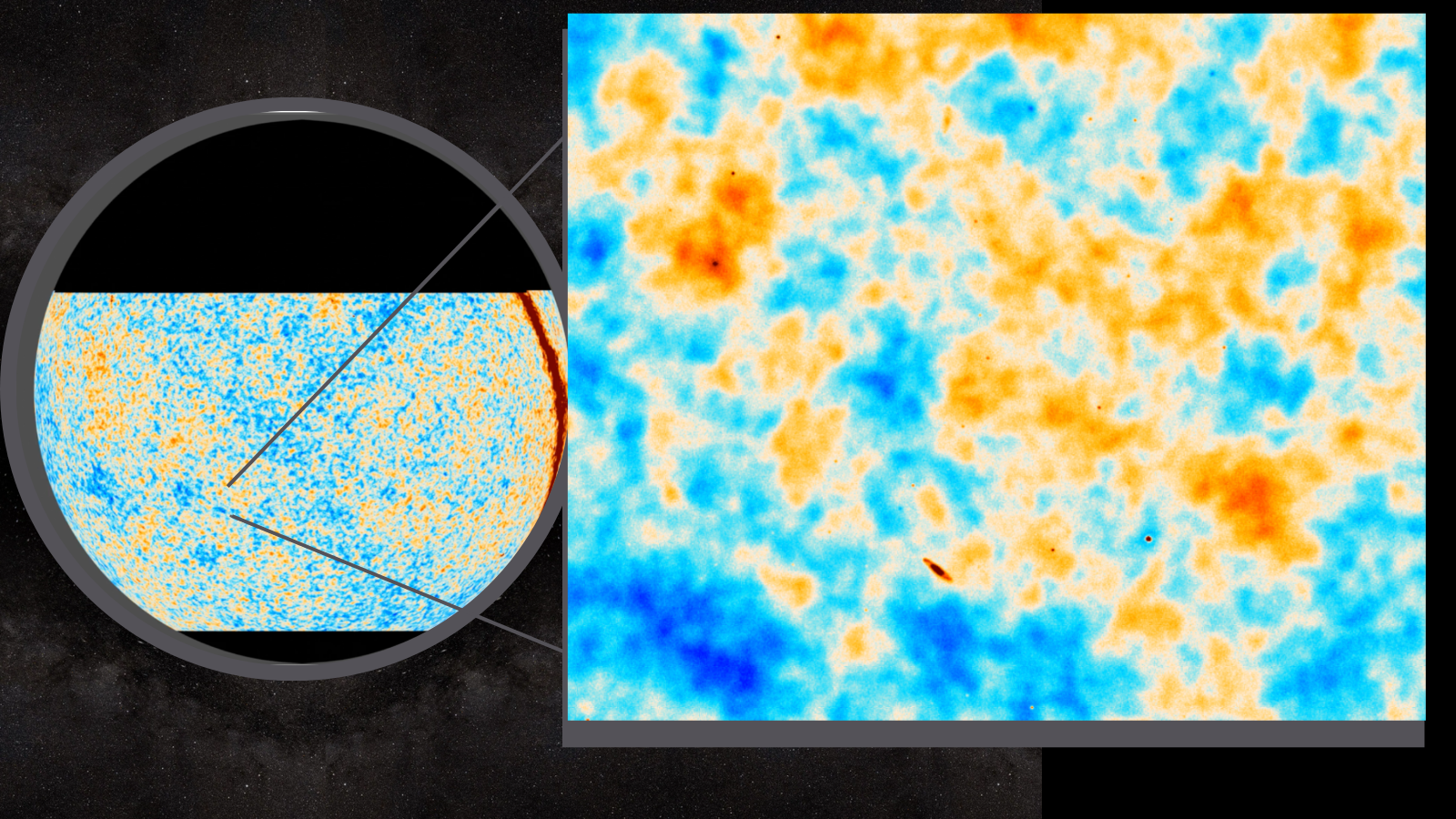

This first light is seen today as the CMB. Though it fills the cosmos almost ubiquitously, there are small variations in the CMB, which scientists call "anisotropies," left behind by tiny fluctuations in the density of matter during the last scattering.

The fact that this cosmic fossil light is the furthest back in time astronomers can hope to see with light, and because it has been around since the earliest epoch of the cosmos, the CMB is an excellent way of tracing the evolution of the universe.

From its position high in the Chilean Andes, ACT captured this light, which has been traveling for over 13 billion years. Previous to this ACT data, the most precise and detailed picture of the CMB had come courtesy of the Planck space telescope.

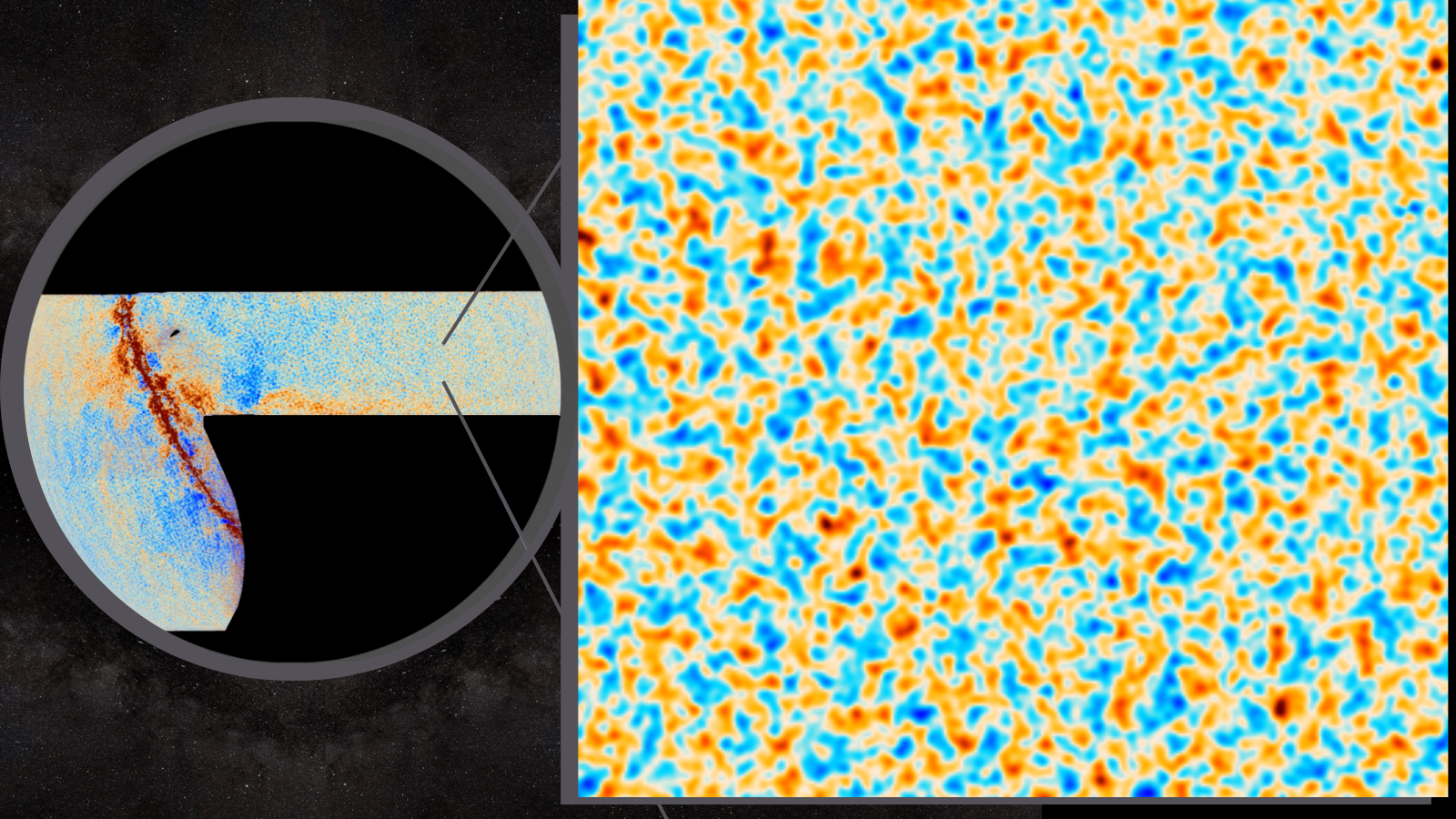

"ACT has five times the resolution of Planck and greater sensitivity," team member and University of Oslo researcher Sigurd Naess said in a statement. "This means the faint polarization signal is now directly visible. There are other contemporary telescopes measuring the polarization with low noise, but none of them cover as much of the sky as ACT does."

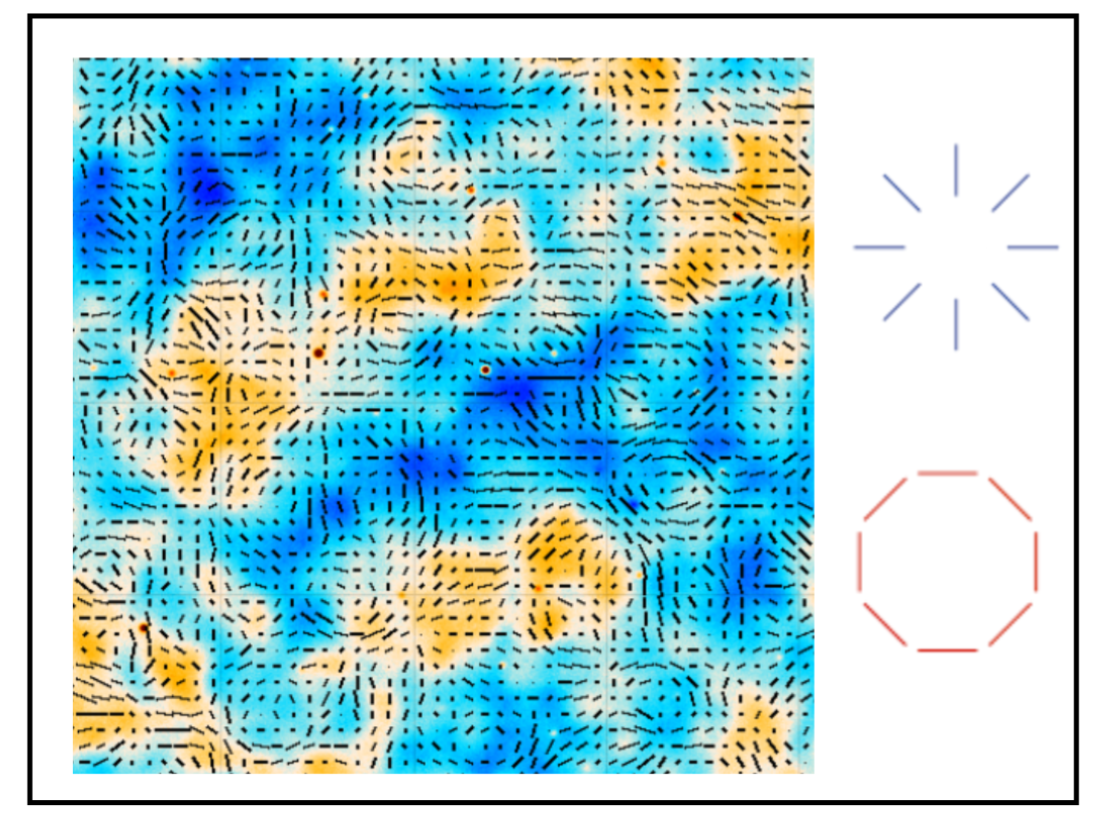

This signature of polarization is important because it reveals how hydrogen and helium gases moved when the universe was in its infancy and filled with only traces of other heavier elements.

"Before, we got to see where things were, and now we also see how they're moving," Staggs said. "Like using tides to infer the presence of the moon, the movement tracked by the light's polarization tells us how strong the pull of gravity was in different parts of space."

With the ACT data, researchers could also see incredibly subtle variations in the density and velocity of the gases that filled the young universe. This includes what appear to be regions of high and low density in this sea of primordial hydrogen and helium. These early cosmic hills and valleys extend millions of light years across, and in the billions of years after the ACT snapshot, gravity pulled their denser regions inwards to birth stars that then formed the first galaxies.

"By looking back to that time, when things were much simpler, we can piece together the story of how our universe evolved to the rich and complex place we find ourselves in today," ACT analysis leader and Princeton University researcher Jo Dunkley said.

A trip back in cosmic time

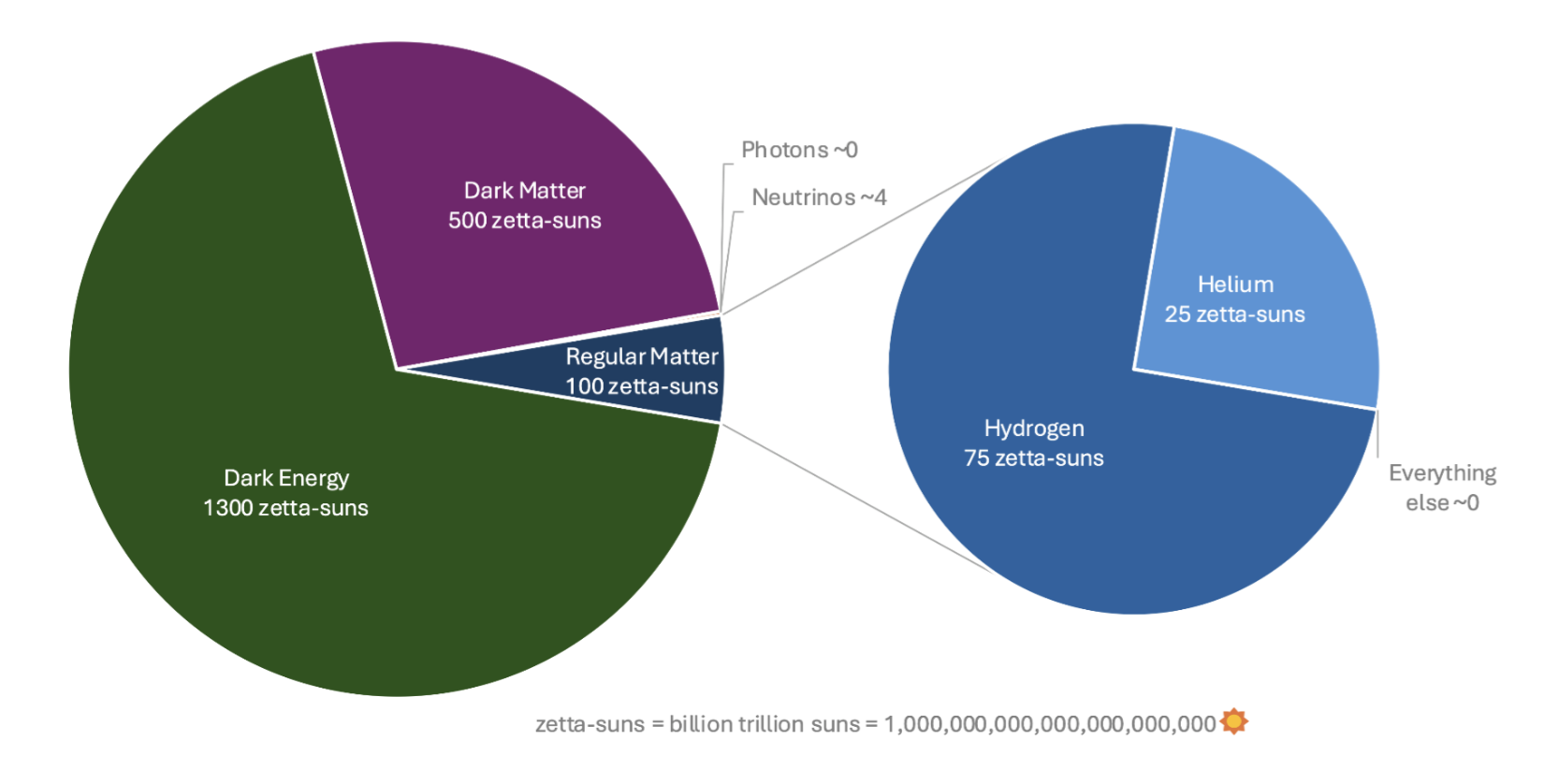

This cosmic trip back in time revealed that the observable universe extends for almost 50 billion light-years in all directions around us. The universe's mass was calculated to be equivalent to around 2 trillion trillion (2 followed by 36 zeroes) suns, or 1,900 "zetta-suns" (a "zetta" refers to a hypothetical star so huge it has a mass 1021 times that of the sun).

Of this total, just 100 zetta suns are composed of the ordinary matter that we see around us on a day-to-day basis. Three-quarters of this mass is hydrogen, and a quarter of it is helium. Another 500 zetta suns worth of mass is accounted for by dark matter, while 1,300 zetta suns worth of mass is accounted for by dark energy, the mysterious force driving the acceleration of the expansion of the cosmos.

Tiny chargeless and almost massless "ghost particles" called neutrinos account for around four zetta-suns of mass. These particles are referred to as the ghosts of the particle zoo because they are so weakly interacting and ubiquitous that around 100 trillion (10 followed by 13 zeroes) neutrinos pass through your body every second, going completely unnoticed.

These amounts agree well with both theoretical models of the cosmos and with observations of galaxies.

The new ACT findings also refined estimates of the age of the universe, conforming to estimates of 13.8 billion years, with an uncertainty of only 0.1%, and the rate at which the cosmos expanded in its earlier eras.

This is possible because matter in the early universe sent out waves through space like ripples spreading out in circles on a pond. These ripples are "frozen into" the cosmic fossil that is the CMB.

"A younger universe would have had to expand more quickly to reach its current size, and the images we measure would appear to be reaching us from closer by," ACT deputy director and University of Pennsylvania researcher Mark Devlin said. "The apparent extent of ripples in the images would be larger in that case, in the same way that a ruler held closer to your face appears larger than one held at arm's length."

Addressing 'Hubble Trouble'

One of the major problems facing cosmology today is the existence of the "Hubble tension." This is the disparity in the rate at which the universe expands, a value called the Hubble constant, depending upon how this expansion is measured.

Using measurements of the movement of nearby galaxies, scientists calculate that the Hubble constant is as great as 73 to 74 kilometers per second per megaparsec (km/s/Mpc). That is larger than the value that scientists obtain when using the CMB to obtain the Hubble constant, which is 67 to 68 km/s/Mpc.

Using these high-resolution images of the CMB, as seen by ACT the team obtained new measurements of the Hubble constant. They found these are in agreement with prior Hubble constant measurements made using the CMB.

One of the major goals for ACT data was to investigate an alternative cosmic model that could account for the Hubble tension. These alternatives included changing the behavior of neutrinos and adding an additional period of accelerating cosmic expansion in the early universe.

"We wanted to see if we could and a cosmological model that matched our data and also predicted a faster expansion rate," Columbia University researcher Colin Hill, who used the ACT data in new research, said. "We have used the CMB as a detector for new particles or fields in the early universe, exploring previously uncharted terrain."

Hill added that the ACT data showed no evidence of such new signals, meaning that the standard model of cosmology has passed an extremely precise test of its accuracy.

"It was slightly surprising to us that we didn't find even partial evidence to support the higher value," Staggs said. "There were a few areas where we thought we might see some partial evidence for explanations of the tension, and they just weren’t there in the data."

ACT completed its observations in 2022 and was decommissioned. Astronomers now turning their attention to the new, more capable Simons Observatory at the same location in Chile.

The new ACT data are shared publicly on NASA’s LAMBDA archive, while the papers spinning out of this ACT data are available on Princeton's Atacama Cosmology Telescope website.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.