New recipe for gravity could unite Einstein's general relativity with quantum physics — and probe the dark universe

If gravity arises from entropy, scientists could unite Einstein's general relativity with the quantum realm while shedding light on dark matter and dark energy.

A new recipe for gravity could help solve some of the universe's greatest mysteries. It suggests that the concept of "quantum gravity" could arise from entropy, possibly solving puzzles put forth by the elusive dark universe — and, if true, this novel theory could also finally unite Albert Einstein's general relativity with the quantum realm.

Since the beginning of the 20th century, Einstein's theory of general relativity has been the best description we have of how gravity works. However, right around when Einstein came up with general relativity, scientists also developed the foundations of quantum mechanics.

Since then, both theories have been tested, revised and improved, standing the test of time and winning over skeptics in the scientific community. There's a problem, though — a big one. They can't work together.

As both theories have been perfected, they continue to defy attempts to unify them. A "theory of everything" that encompasses both general relativity and quantum physics has thwarted the efforts of minds as great as Stephen Hawking, and even Einstein himself.

One of the major stumbling blocks here concerns the fact that there is no theory of "quantum gravity."

But this is where Ginestra Bianconi, a professor of Applied Mathematics at Queen Mary University of London, comes in.

She suggests a framework that would see quantum gravity arising from so-called "quantum relative entropy," a concept that measures how dissimilar two quantum states are.

General relativity and the dark universe

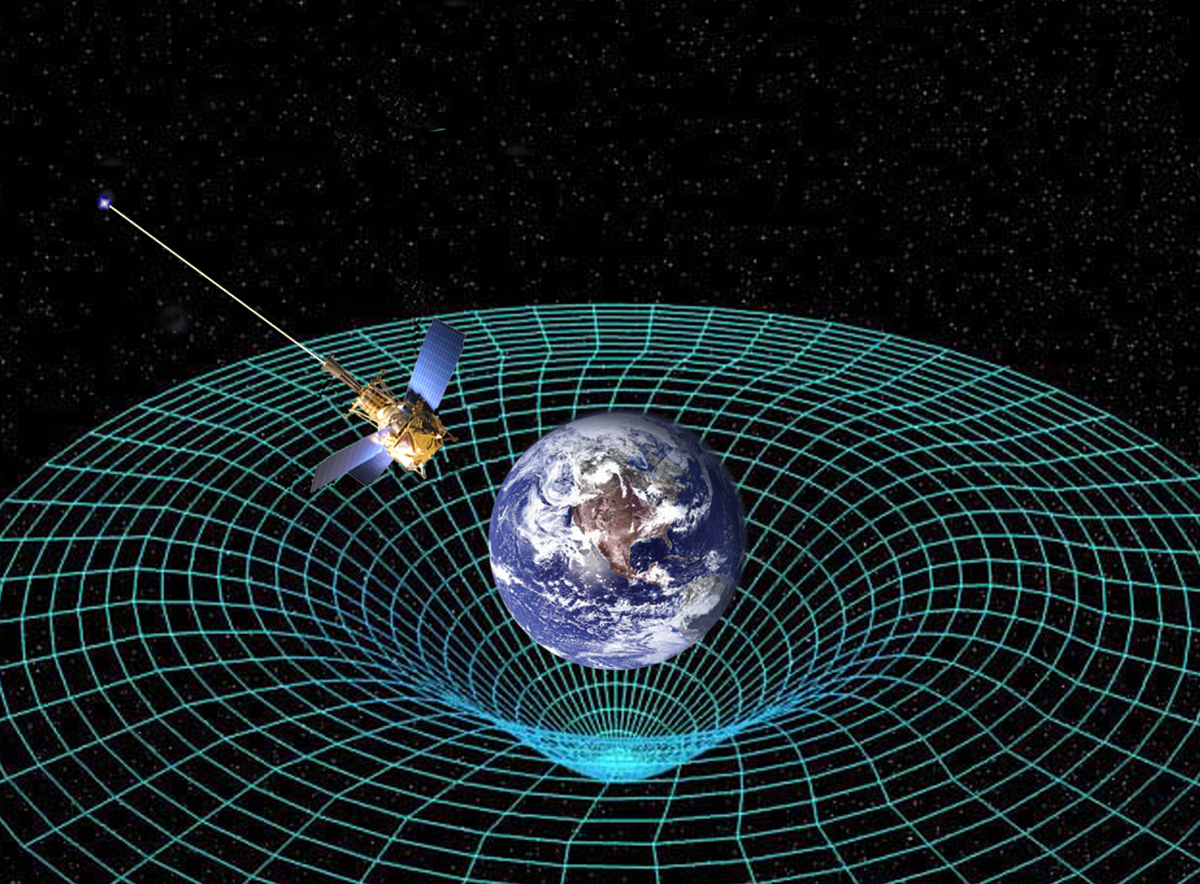

Developed in 1915, general relativity suggests that gravity arises because bodies with mass cause the fabric of spacetime (the four-dimensional unification of space and time) to warp. The greater the mass of an object, the more extreme the warping of spacetime and, thus, the more powerful the object's gravitational influence.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This has been verified time and time again, thus enabling general relativity to supersede Newton's theory of gravity as the best description of the universe on cosmic scales.

However, general relativity cannot explain everything.

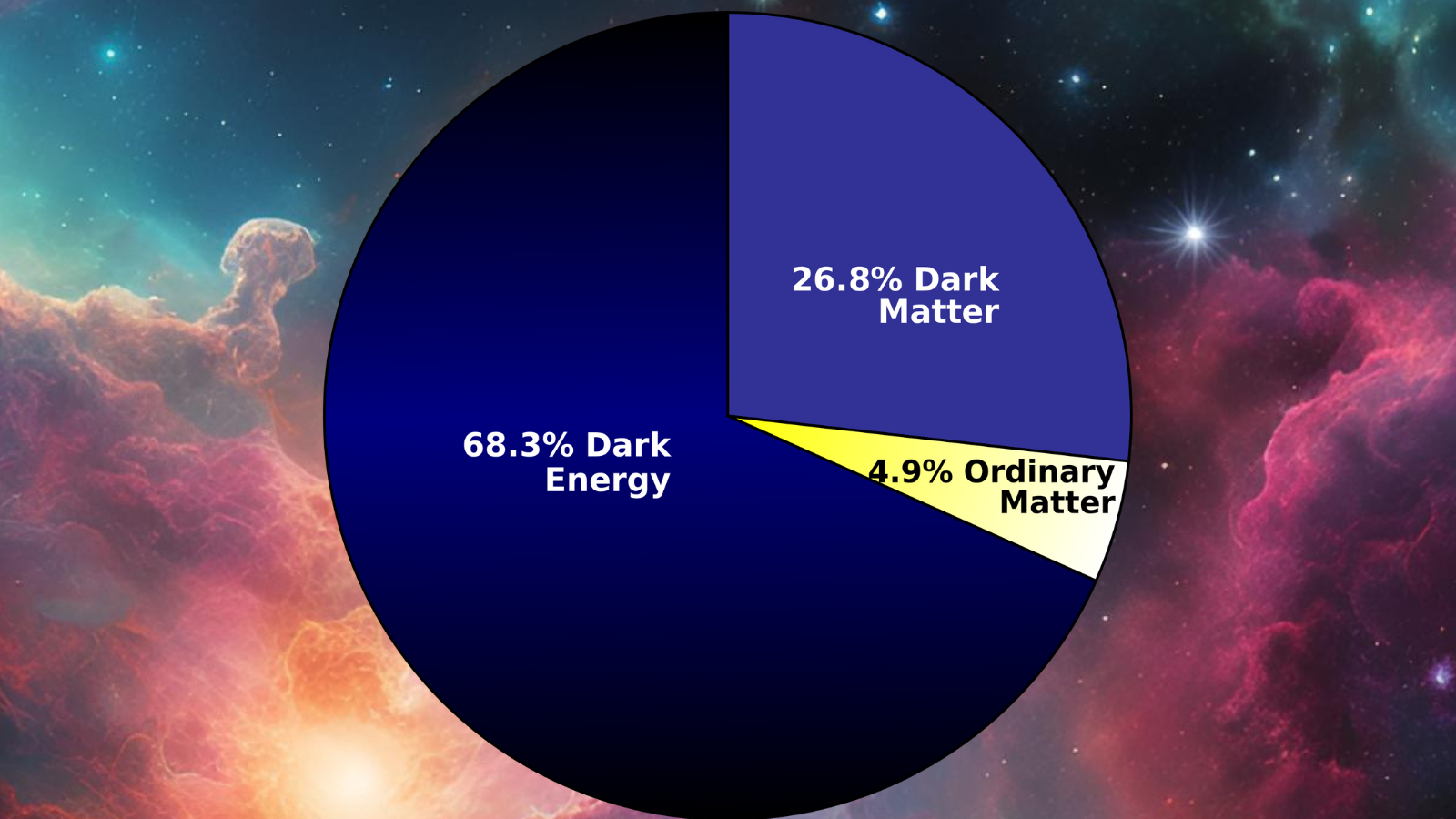

Dark matter, the mysterious substance that outweighs ordinary matter by a factor of five, and dark energy, the unknown component of the universe driving its accelerated expansion, for instance, are not accounted for by general relativity.

That's a big problem because dark energy accounts for 68% of the total matter and energy in the universe, and dark matter accounts for another 27% or so. That means the "dark universe" accounts for around 95% of the matter-energy budget of the cosmos, so the "stuff" we can comfortably describe with general relativity represents just 5% of the energy and matter in the universe.

Then, there's the fact that Einstein's theory of gravity won't "play nice" with quantum physics.

The new framework — or "recipe" for gravity, if you will — takes the metric of spacetime from general relativity, which describes the geometry of space and time based on distances and intervals between events, and treats it like a mathematical entity called an operator.

Operators are used in quantum physics to perform transformations on quantum states arising through changes in physical factors. This general-relativity-based operator leads to a new "entropic action," and to modified Einstein equations.

At low energies and in regions of space where there is little curvature, and thus little gravity, these equations replicate those of general relativity.

This new research goes further, though. It predicts the emergence of a small positive valued cosmological constant. That's significant because its value better aligns with observations of the universe's accelerated expansion under the influence of dark energy than other current theories do.

In addition to this, something called a "G-field" emerges from this theory that could account for the gravitational influence of dark matter.

"This work proposes that quantum gravity has an entropic origin and suggests that the G-field might be a candidate for dark matter," Bianconi said in a statement. "Additionally, the emergent cosmological constant predicted by our model could help resolve the discrepancy between theoretical predictions and experimental observations of the universe’s expansion."

Of course, it is still very early days for this theory, but given how profound its implications could be for our fundamental understanding of the cosmos, it's likely worth exploring.

Bianconi's research was published on Monday (March 3) in the journal Physical Review D.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.