Geysers on Saturn's moon Enceladus may not come from its underground ocean

A theory involving a "mushy zone" of ice along the moon’s fissures could explain the enormous plumes erupting from its south pole.

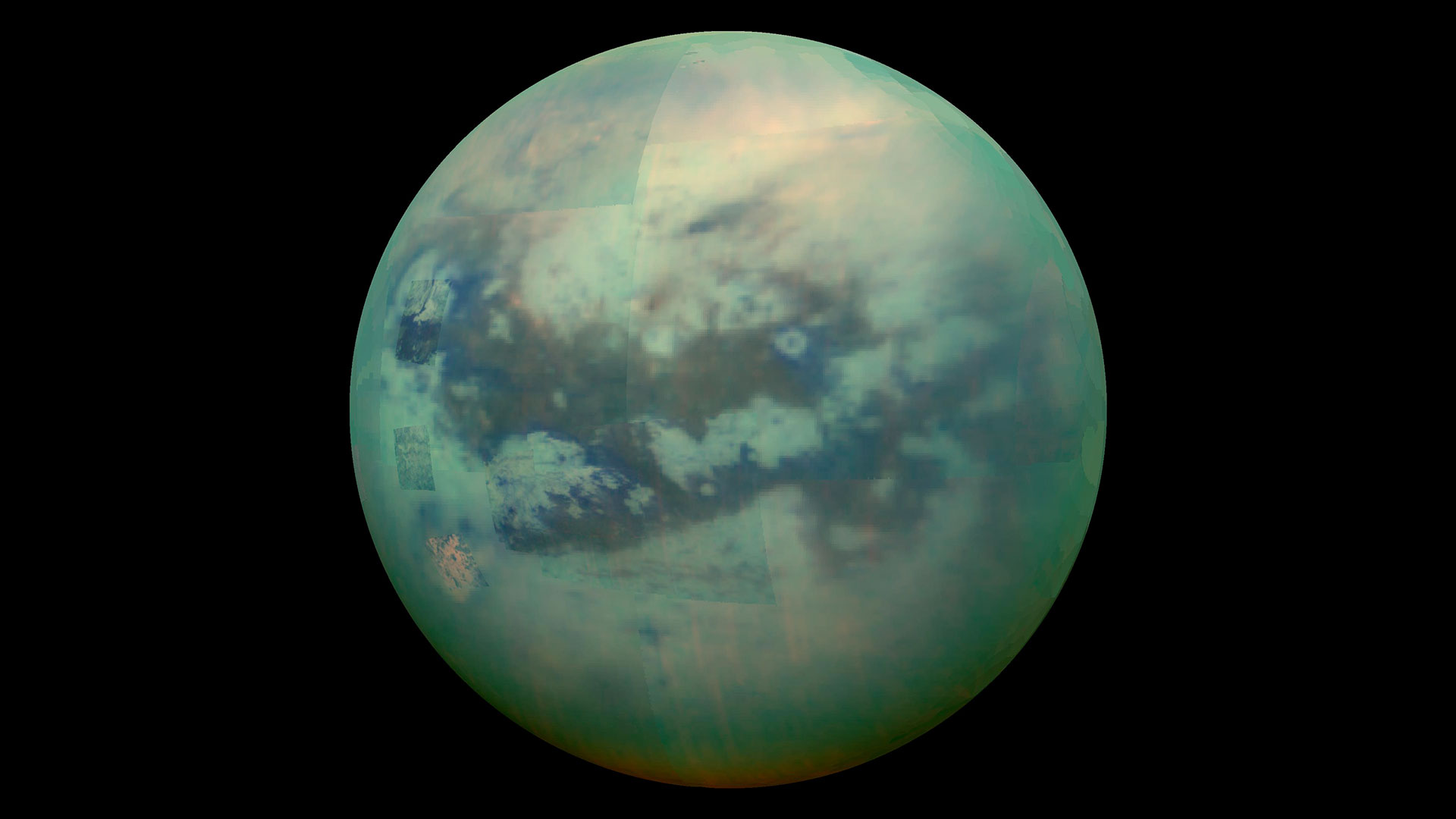

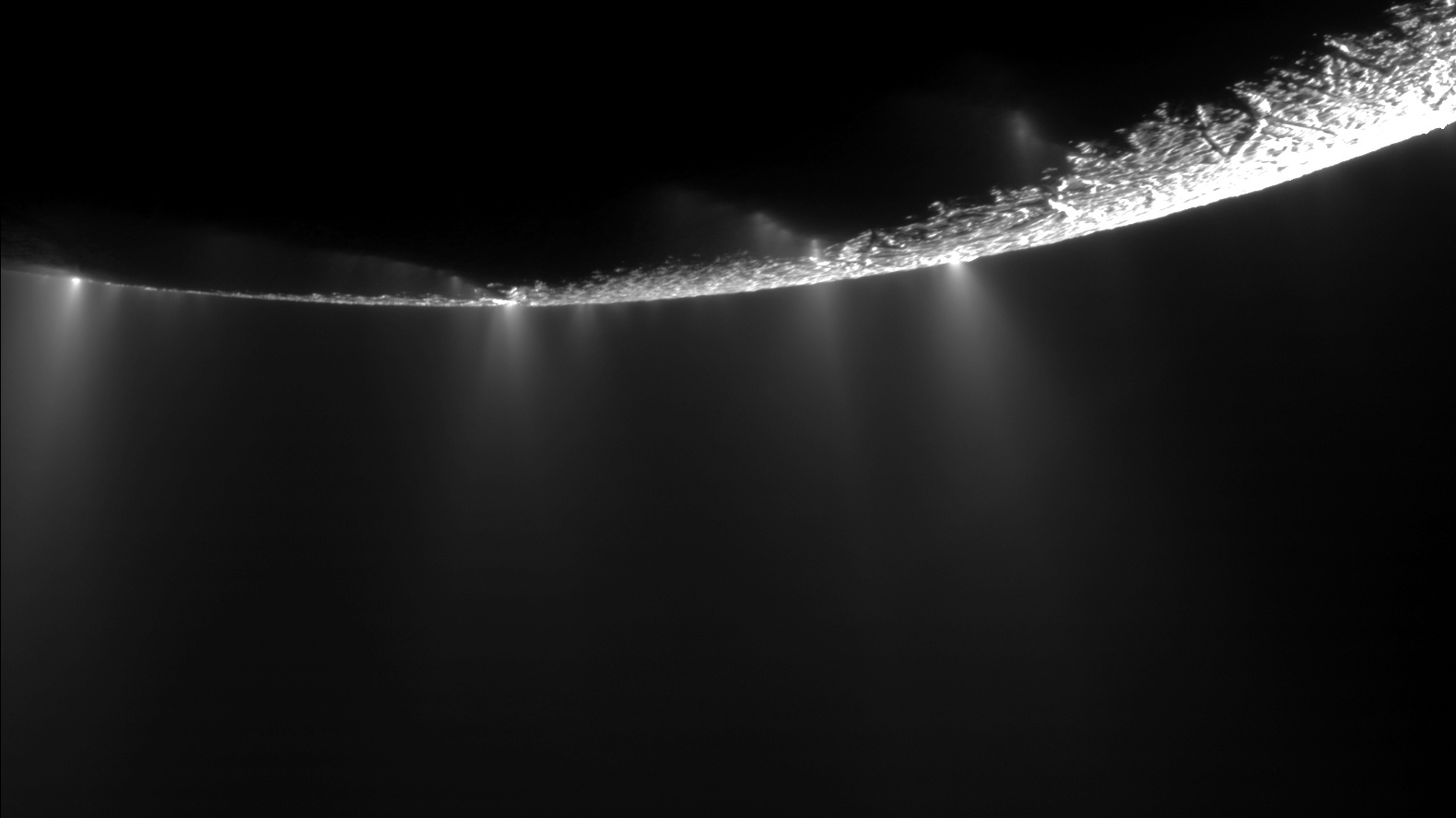

Saturn's icy moon Enceladus has long been considered a potential home for life in our solar system. In 2005, NASA's Cassini spacecraft first discovered towering plumes of water vapor erupting from the moon's frozen surface, for instance, and it was later theorized that these geysers come from a vast — potentially habitable — underground ocean. Liquid from the ocean, scientists believed, could be escaping through cracks in the moon's icy crust.

Researchers at Dartmouth College set out to understand exactly how these geysers form, and ultimately found themselves suggesting that the observed plumes might not come from a hidden ocean under the moon's surface at all. Instead, the team suggests the water in the geysers could originate from melted surface ice on the Saturnian moon, challenging the idea that the eruptions are directly linked to the deep subsurface ocean — and, ultimately, that Enceladus could support life (as we know it, at least).

The team believes there are two major problems with the idea that the plumes come from an underground ocean. First, it would be very difficult for a crack to cut all the way through the moon's thick ice shell, and second, even if a crack did reach the ocean, it's unclear how water from deep below would travel up through it.

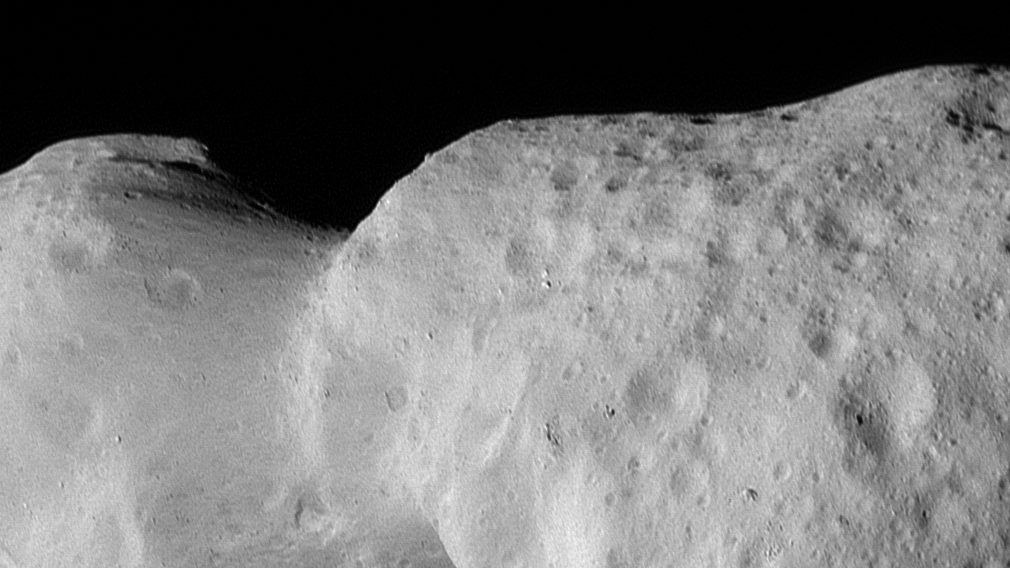

Another possibility the researchers describe in their paper is that shear heating — friction-generated heat from ice rubbing against itself — occurs along "tiger fractures" in Enceladus's salty ice shell.

"We postulate that the reservoir is not necessarily a subsurface ocean, but could instead be a mushy zone within the ice shell,” they wrote in their paper. "A connection from the surface to a reservoir is still required, but it is not necessary for the fracture to extend all the way through the ice shell."

Salt within the moon's icy shell lowers the melting point of the ice — just like how salt is used on roads in winter to prevent them from freezing over. This effect, combined with heat from friction along fractures, creates a slushy mix of partially melted ice and salty water. According to the researchers, this could provide a near-liquid source for the plumes seen erupting from Enceladus's south pole.

The double ridges observed around the tiger stripe may also provide an additional line of evidence for shear heating. "[Previous studies] describe double-ridge formation on icy satellites building on evidence from refreezing in the surface snow of the Greenland Ice Sheet," the study authors wrote. "As liquid water freezes in a near-surface reservoir, it expands and drives the sides of the crack vertically. The mushy zone that we propose could be a near-surface water source and the double ridges could be evidence for episodic geyser occurences followed by refreezing dormant periods."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The team also argues that the ratio of gases identified in the plumes by Cassini, especially hydrogen, could be sufficiently explained by the partial melting of clathrates — crystal structures formed within ice and rock that can trap gases.. "Molecular hydrogen could be trapped in clathrates with stabilization from [methane] and [carbon dioxide] or persist as entrained gas bubbles within the ice shell, as found in ice sheets on Earth," the authors stated.

Due to hydrogen's volatility, partial melting could allow some of it to escape while trapping carbon dioxide and methane, leading to the higher hydrogen ratio observed in the plumes. As ice flows, refreezes, and undergoes tectonic shifts, salty ice and clathrates are resupplied to the "mushy zone," sustaining the plume composition.

"With a mushy zone sourcing the plume material, the salt, nanoparticles, and gas clathrates would need to be replenished over time in order to maintain the levels observed by Cassini. Although we do not model the replenishment processes here, it is an area of future work," the scientists concluded.

The study was published on Feb. 5 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

A chemist turned science writer, Victoria Corless completed her Ph.D. in organic synthesis at the University of Toronto and, ever the cliché, realized lab work was not something she wanted to do for the rest of her days. After dabbling in science writing and a brief stint as a medical writer, Victoria joined Wiley’s Advanced Science News where she works as an editor and writer. On the side, she freelances for various outlets, including Research2Reality and Chemistry World.