Scientists find rare double-star spiral doomed for supernova explosion

"When I first spotted this system with a very high total mass on our galactic doorstep, I was immediately excited."

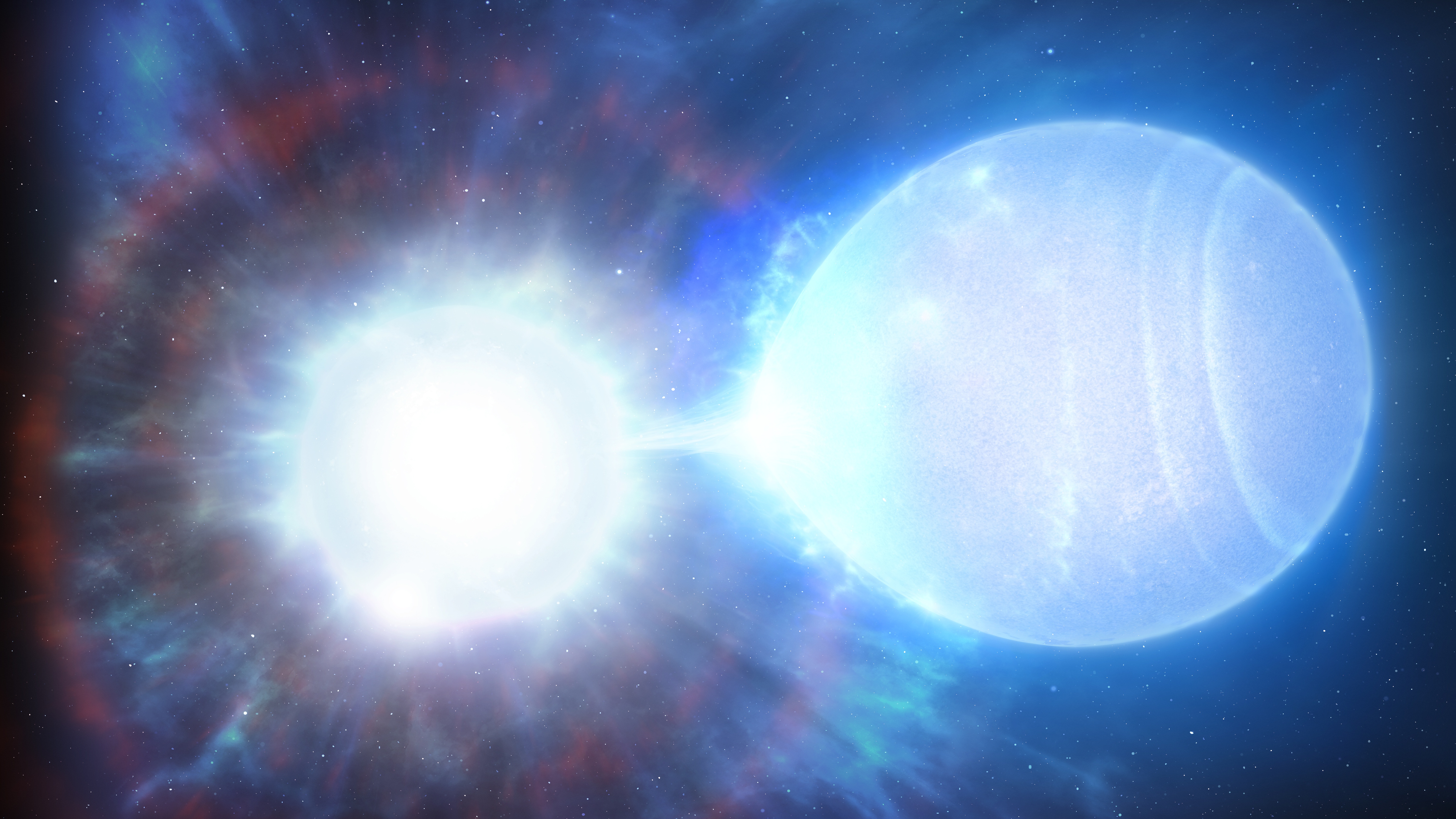

A pair of rare, compact white dwarf stars that are set to collide in about 23 billion years have been spotted by researchers at the University of Warwick. After converging, the binary star system will explode into a Type 1a supernova. Scientists have long predicted that two orbiting white dwarf stars are responsible for creating Type 1a supernovas, but this discovery marks the first time such a star system headed down that path has been observed.

The binary star system sits roughly 150 light-years from Earth. It's also incredibly heavy, with a combined mass equal to about 1.56 times that of the sun. With a mass so high, the doomed white dwarf stars really are destined to explode, the team says.

"When I first spotted this system with a very high total mass on our galactic doorstep, I was immediately excited," James Munday, a Ph.D. researcher at the University of Warwick and leader of the investigation, said in a statement.

A white dwarf star is basically the corpse of a low-mass star that lost its outer layers. That can happen when a star runs out its fuel supply needed to maintain nuclear fusion reactions happening at its core. What's left behind is the raw stellar core — a white dwarf. These particular white dwarf stars scientists are excited about will eventually begin a closer orbit around one another. Then, the heavier of the two will accumulate material from the less weighty partner. That'll be what causes the supernova event.

"With an international team of astronomers, four based at The University of Warwick, we immediately chased this system on some of the biggest optical telescopes in the world to determine exactly how compact it is," Munday added.

Type 1a supernovas are very helpful for scientists, because supernovas tend to explode with roughly the same amount of energy. This consistent energy measurement allows scientists to predict the luminosity, or intrinsic brightness of the supernova.

In measuring the luminosity, scientists are able to calculate vast distances in the universe. Using traditional measurements for these distances isn't practical, of course, due to the vast scale of the universe, so scientists use "standard candles," or objects with a known intrinsic brightness, as milestones on a cosmic "ruler" of sorts.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

So, with this new discovery, scientists have found the type of star system that creates these helpful measuring tools. "At last, we as a community can now account for a few percent of the rate of Type 1a supernovas across the Milky Way with certainty," Munday said.

At present, the white dwarfs spiral around each other with an orbital rate of more than 14 hours. After a few billion years, the stars will grow closer. Eventually they'll move faster, orbiting each other at a rate of about 30 to 40 seconds. Then, the supernova explosion — one with more power than a thousand trillion trillion nuclear bombs — will detonate.

"This is [a] very significant discovery," Dr. Ingrid Pelisoli, Assistant Professor at The University of Warwick and third author, said in the same statement. Because the star system appears relatively close, Pelisoli reasons, these types of white dwarf pairs must be relatively common — otherwise, the team would've had to look much farther to find them.

"Finding this system is not the end of the story though, our survey searching for Type 1a supernova progenitors is still ongoing and we expect more exciting discoveries in the future," Pelisoli added. "Little by little, we are getting closer to solving the mystery of the origin of Type 1a explosions."

The research on the white dwarf stars was published April 4 in the journal Nature.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Julian Dossett is a freelance writer living in Santa Fe, New Mexico. He primarily covers the rocket industry and space exploration and, in addition to science writing, contributes travel stories to New Mexico Magazine. In 2022 and 2024, his travel writing earned IRMA Awards. Previously, he worked as a staff writer at CNET. He graduated from Texas State University in San Marcos in 2011 with a B.A. in philosophy. He owns a large collection of sci-fi pulp magazines from the 1960s.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.