What would happen if the Milky Way's black hole erupted? This distant galaxy paints a terrifying picture

"Could our galaxy one day experience similar high-energy phenomena that will have serious consequences for the survival of precious life in it?"

A cosmic anomaly detected in a distant galaxy could portend a terrifying future for life in the Milky Way. The discovery suggests that our models of galactic evolution could be inaccurate.

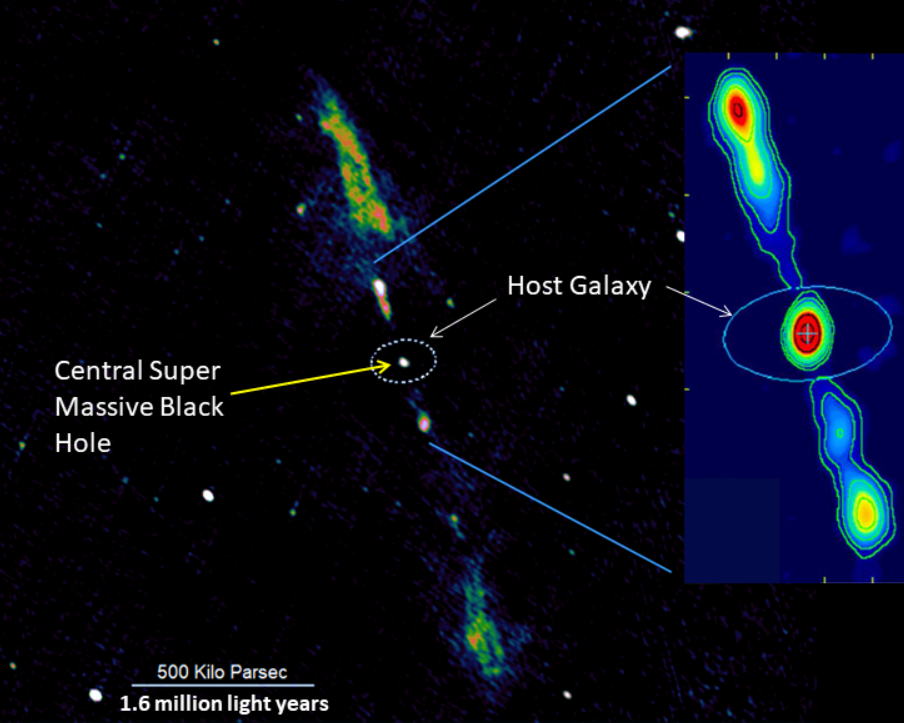

Astronomers have detected an erupting supermassive black hole producing some of the largest jets ever seen bursting from a galaxy with the same shape as our own. The galaxy in question also possesses vastly more dark matter than the Milky Way, hinting at a connection between active black holes and the abundance of the universe's most mysterious "stuff."

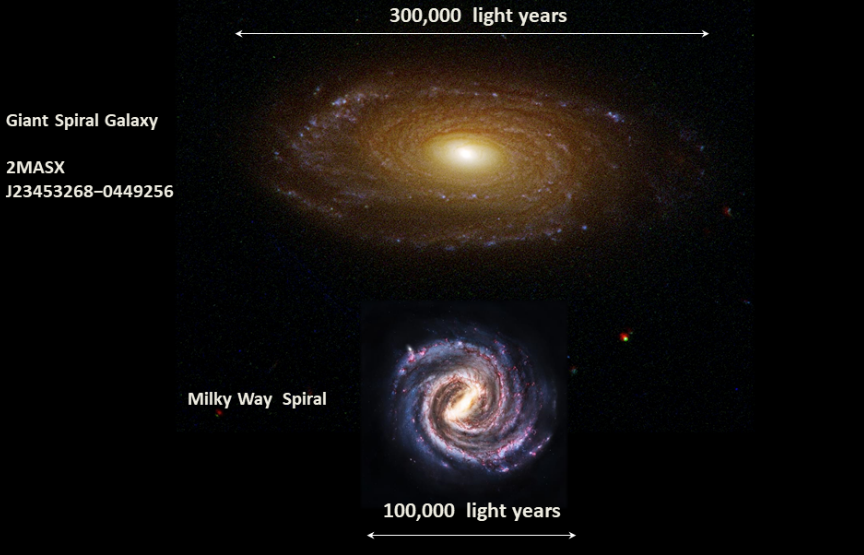

The jets erupting from the massive spiral galaxy 2MASX J23453268−0449256 (J2345-0449), which is three times the size of the Milky Way and is located 947 million light-years away, are themselves 6 million light-years long. And if the supermassive black hole in J2345-0449, which has an estimated mass equivalent to 1.4 billion suns, can erupt so violently, could our galaxy's supermassive black hole Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*) also blow its top? And if so, what would this mean for life in the Milky Way?

While larger jets have been observed in the past (most notably the jet named "Porphyrion," which stretches for 23 million light-years), such monstrous emissions have mainly been associated with elliptical galaxies, not with spiral galaxies.

"This discovery is more than just an oddity – it forces us to rethink how galaxies evolve and how supermassive black holes grow in them and shape their environments," team leader Joydeep Bagchi of CHRIST University, Bangalore, said in a statement. "If a spiral galaxy can not only survive but thrive under such extreme conditions, what does this mean for the future of galaxies like our own Milky Way?

"Could our galaxy one day experience similar high-energy phenomena that will have serious consequences for the survival of precious life in it?"

Death spiral?

The team detected this remarkable radio jet outburst using the Hubble Space Telescope, the Giant Metrewave Radio Telescope, and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA).

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Previously, scientists had thought that such a violent and titanic jet erupting from the supermassive black hole at the heart of a spiral galaxy would destroy the structure of that galaxy, particularly the distinctive spiral arms that give these galaxies their names.

However, J2345-0449 appears to be tranquil, and it has managed to retain its morphology, including its spiral arms, its bright churning "nuclear bar" of stars, and a stellar ring — despite possessing one of the most violent supermassive black holes ever seen in a spiral galaxy.

As if this wasn't odd enough, this distant galaxy is surrounded by a huge halo of gas. In many galaxies, this material would be cooling and condensing to produce new stars. However, in J2345-0449, the central black hole is acting as a cosmic furnace, heating this halo of gas, producing X-ray emissions, and preventing it from creating new stars.

Cosmic rays, gamma rays, and X-rays, all associated with the massive jets emerging from the black hole at the heart of this galaxy, threaten any life that may have emerged in J2345-0449.

What if Sgr A* binges on a star?

As mentioned above, there are some major differences between J2345-0449 and the Milky Way, including the fact our galaxy is a third of the size of its distant cousin. The black holes at the hearts of both galaxies are also different, or as different as supermassive black holes get anyway.

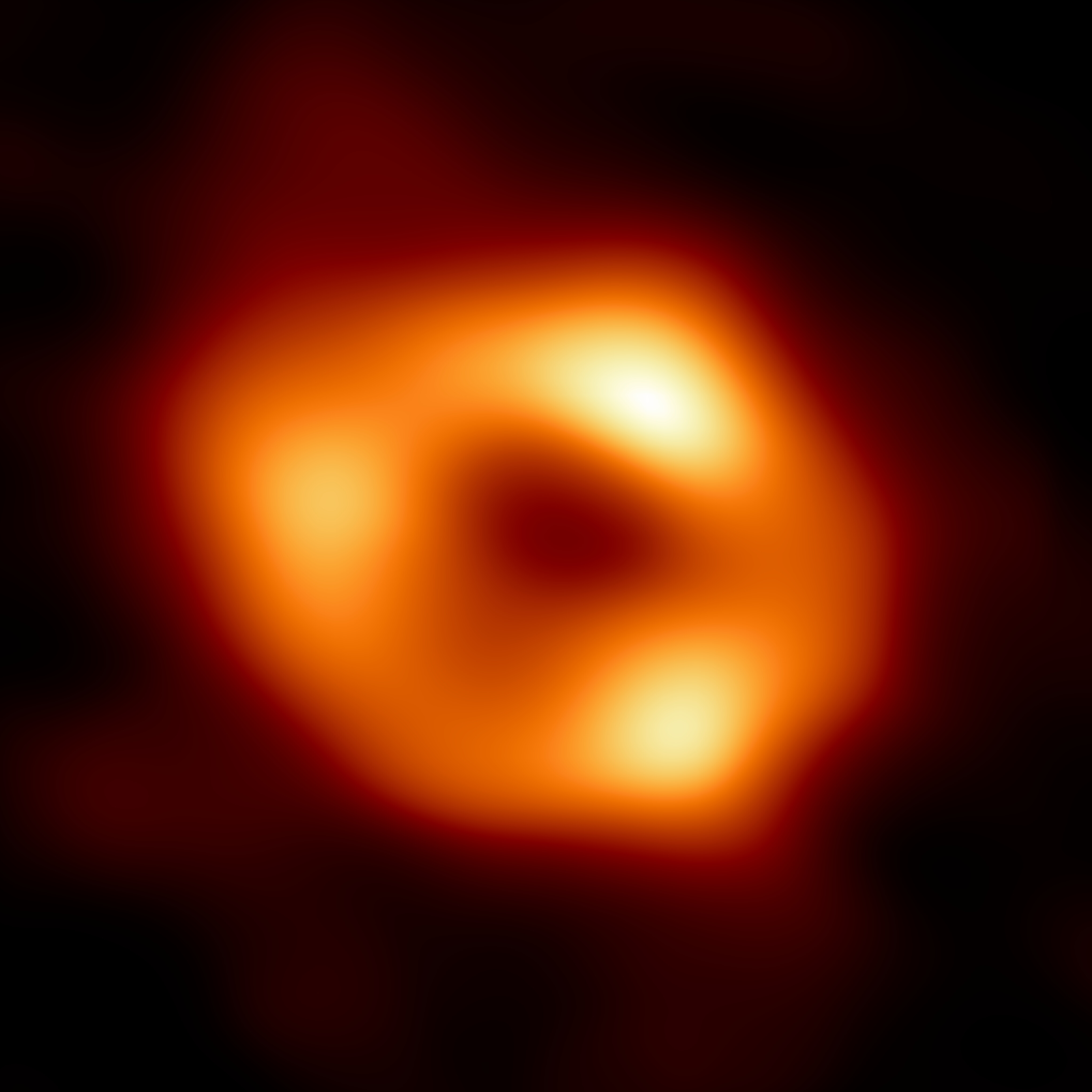

While the supermassive black hole in J2345-0449 is estimated to be between 250 million and 1.4 billion solar masses (there is a big uncertainty because J2345-0449 lacks a central bulge, making the mass of its black hole hard to measure), Sgr A* is much more diminutive with a mass of around 4.3 million suns.

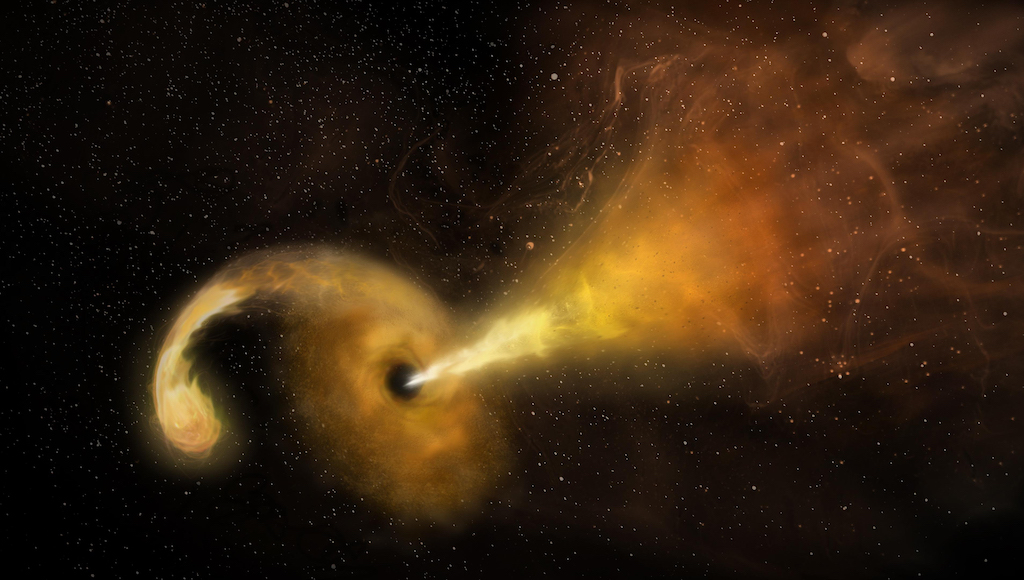

The black hole of J2345-0449 is so turbulent because it greedily feasts on abundant gas and dust swirling around it in a flattened cloud called an accretion disk. Material that the black hole doesn't devour is channeled to the poles of this cosmic titan, from where it is blasted out at near-light speeds as these extraordinary twin jets.

Sgr A* doesn't currently have such powerful jets (there is debate about whether it has any jets at all) because it isn't feeding on much material. In fact, if our central supermassive black hole were a human, it would be as if it sustained itself on a grain of rice every one million years.

However, this situation could change on very short notice if Sgr A* were to snag itself a large gas cloud or a star and begin devouring it. Such an occurrence is called a tidal disruption event (TDE), and while we've seen many such events in other galaxies, we've never seen one from Sgr A*.

Were Sgr A* to rip apart a star in a TDE, the material from the star would fall around our black hole, forming an accretion disk. And that would result in the production of astrophysical jets.

The impact of such jets would depend on their orientation, their strength, and the amount of energy they pump out.

If a jet from Sgr A*, which is around 27,000 light-years away, was pointed directly at the solar system, it would be capable of stripping away planetary atmospheres and damaging the DNA of life here on Earth. The radiation associated with these jets could increase mutation rates.

If Earth were to take a direct hit from such a jet, the high-energy particles within it could degrade our ozone layer and lead to a mass extinction.

Even if such a jet isn't angled toward Earth, it could still have disastrous implications for the Milky Way on a larger scale. Were a jet to slam into the interstellar medium, the gas and dust between the stars in our galaxy, it could heat them and curtail star formation, just as it has done in J2345-0449.

This would not be unprecedented in the Milky Way, which scientists believe was once ravaged by vast radio jets. However, predicting if and when such jets could erupt from Sgr A* again isn't as easy as spotting evidence of its historical activity.

There is another enigma surrounding J2345-0449 that astronomers will be keen to investigate.

The dark matter connection

During their study of J2345-0449, the team also found that this galaxy, three times the size of the Milky Way, appears to contain ten times the dark matter that our galaxy does.

Dark matter is effectively invisible because, unlike the ordinary matter that composes stars, planets, moons, our bodies, and everything we see around us, it doesn't interact with light.

Dark matter does interact with gravity, though, and this is important for J2345-0449. This distant, massive galaxy is spinning so rapidly that it takes a vast amount of dark matter to maintain its structure and prevent it from flying apart.

This is the first time that astronomers have drawn the connection between the dark matter content of a galaxy, that galaxy's structure, and the activity of its central supermassive black hole.

The team thinks that further establishing this connection could open up an entirely new frontier of scientific study.

"Understanding these rare galaxies could provide vital clues about the unseen forces governing the universe – including the nature of dark matter, the long-term fate of galaxies, and the origin of life," team member Shankar Ray, also from CHRIST University, Bangalore, said. "Ultimately, this study brings us one step closer to unraveling the mysteries of the cosmos, reminding us that the universe still holds surprises beyond our imagination."

The team's research was published on Thursday (March 20) in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.