Moon pit diver: This tiny rover could explore the lunar underworld

The Pitranger prototype is paving the way here on Earth.

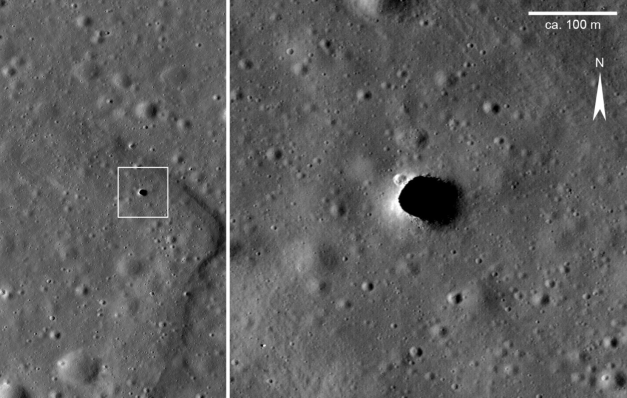

Dotting the moon's harsh landscape are steep-walled holes known as pits. These features, also called skylights, may connect with far-reaching, subsurface lava tubes that were shaped billions of years ago by a then geologically lively moon.

New technologies are being harnessed that could allow exploration of skylights, lava tubes and caverns on the moon — underground environments that human explorers may be able to exploit in the not-too-distant future.

"Caves, if accessible, could be havens from radiation, temperature extremes and micrometeorite hazards of the moon's surface," said William "Red" Whittaker, a research professor at the Robotics Institute at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh.

Related: Home on the moon: How to build a lunar colony (infographic)

Windows to great unknowns

Whittaker, a pioneer in designing robots for off-Earth exploration, said that significant progress has been made in assembling a short-lived robot that's long on capability to probe deep pits on the moon.

Whitaker provided an update on his work during a virtual meeting held in September by the NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) Program. NIAC has funded his team's investigation into effective designs for mobile robots to explore subsurface environments on other worlds.

"Lunar skylights are windows to great unknowns both within and below the moon's surface," Whittaker said. "Micro-rover pit exploration is affordable and viable in the near term."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Moreover, the discovery of hundreds of lunar skylights over the last decade raises the possibility that some of them could provide long-dreamed-of access to caves.

Sinkhole testing

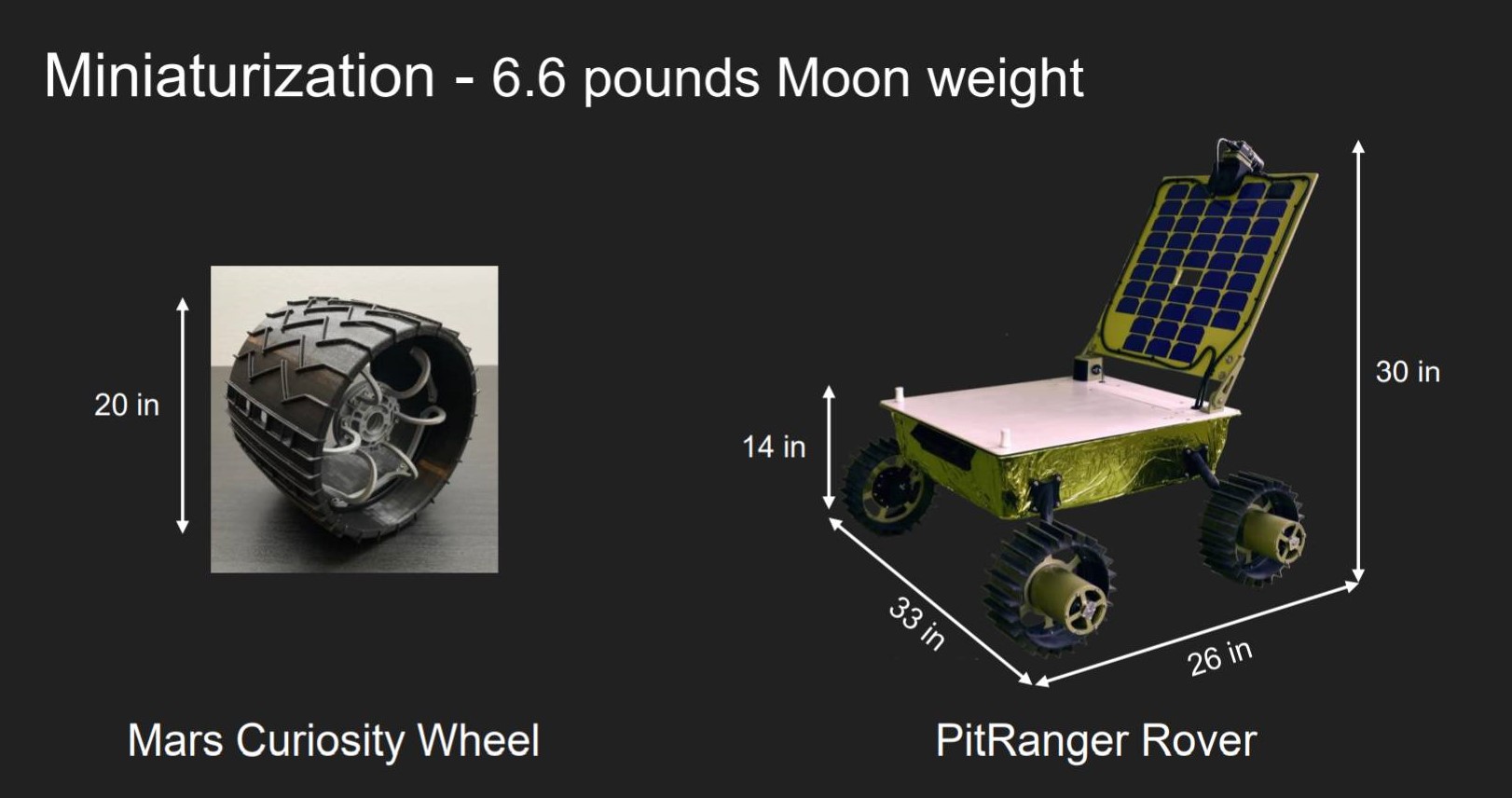

Whittaker and his colleagues have been busily building a PitRanger, a terrestrial prototype of a 33-lb. (15 kilograms) lunar mini-robot.

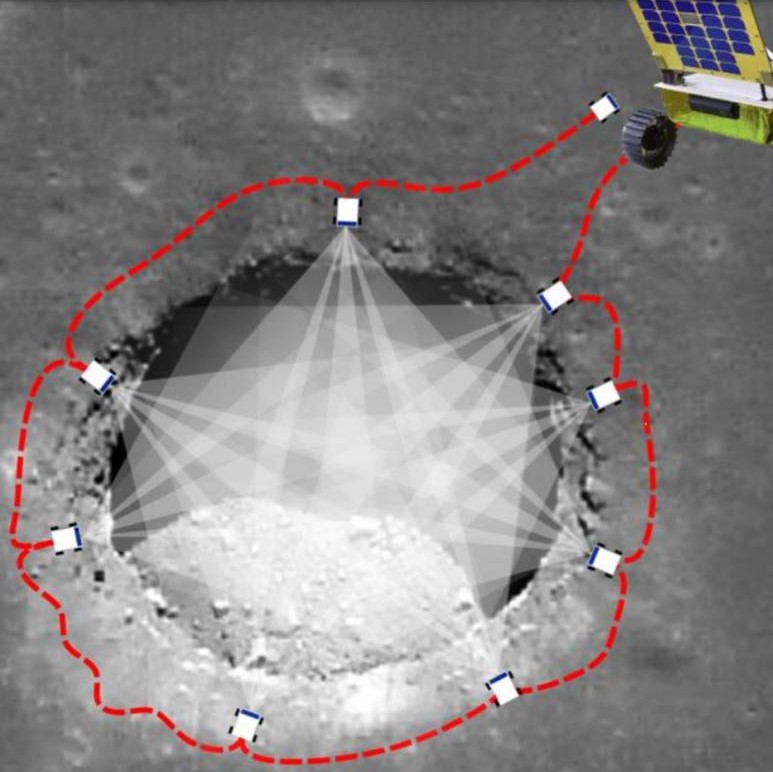

The researchers modeled and measured a pit on Earth to help flesh out the robot's design and capabilities. A photogrammetric model of the pit was created from 10,000 rover-perspective images captured from 26 locations around the West Desert Sinkhole in Utah. That feature is nearly 330 feet (100 meters) deep and roughly 246 feet (75 m) wide.

The PitRanger rover is outfitted with a telephoto camera and a pan unit at the top of its solar panel. The little robot uses a panel tilt mechanism to aim the camera into the pit.

Rovers for moon pit exploration missions must necessarily be distinct from those that have come before, Whittaker said. They must be compatible with small landers and be able to negotiate steep pit aprons, provide powerful computing and obtain the required cross-pit images, he said.

Lunar shelter: Moon caves could protect astronauts

Fast exploration

"The scenario is to rove to a pit with a micro-rover, peer into the pit, acquire images of walls, floors, caverns, and then generate pit models," Whittaker said. Autonomy for fast exploration is the critical technology, he added, since the small, solar-powered rovers won't be able to carry direct-to-Earth radio for supervision or guidance.

In addition, "the rover must succeed in a single illumination period" on the moon, because it needs the sun for energy and heating, Whittaker said. (A lunar day lasts about 14 Earth days, and the lunar night is equally long.) "It only has 12 days, not 12 years, to complete its mission."

The small lunar rover would be imbued with the software smarts to prune and pre-process "best of" images taken of a lunar pit and then transfer that visual feast to the lander for modeling. The little robot would do this work repeatedly, wheeling back to the pit multiple times to acquire additional slugs of images and measurements.

Built-in rover autonomy would generate behaviors, plans and imaging decisions that command the machinery to occupy strategic overlooks around a pit. Each visit would acquire thousands of relevant images for periodic return to and download into the lander.

On average, the rover's top speed would be 1 inch (2.5 centimeters) per second.

'Pit bull' attributes

Initial pit models transmitted from the lander that reach Earth would be further improved as more images arrive. The ultimate outcome would be a high-fidelity, 3D-quality pit model, Whittaker said.

Overlooks of the pit would be identified, Whittaker added, by balancing the value of imagery against the risks encountered by the rover while it rolls to the pit's rim. At each overlook, images would be acquired at many pan/tilt combinations to view the far wall and floor of the pit.

The result of all this work would be a stunning, up-close profile of the targeted lunar pit, a far superior look-see compared to a moon-circling orbiter, Whittaker said.

Beyond the prospect of gauging the promise of underground habitats for moon explorers, lunar pits are also windows to unique science.

"Pit walls offer the only observable pristine geology on the moon. They are unique opportunities to observe volcanology, morphology and much more," Whittaker said.

In the end, it's all about tapping the power of miniaturization that makes the "pit bull" attributes of a micro-rover achievable.

"It is a little bit like taking Alexander Graham Bell's first telephone and getting it into the cell phones we all carry around," Whittaker concluded.

Leonard David is author of the recently released book, "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published by National Geographic in May 2019. A longtime writer for Space.com, David has been reporting on the space industry for more than five decades. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.