Saturn's moon Titan has a weird organic chemical in its atmosphere

Saturn's moon Titan just keeps getting weirder — and more tantalizing when it comes to scientists' hopes for life beyond Earth.

Titan is perhaps the most Earth-like place in our solar system, except the ingredients are jumbled up: ocean below ground, landforms of water ice instead of rock, rains of organic compounds, an atmosphere even denser than our own. Now, two new research findings add still more intrigue to the strange moon, identifying an unexpected chemical in Titan's atmosphere and evidence of more complicated surface phenomena than scientists had previously realized.

"We think of Titan as a real-life laboratory where we can see similar chemistry to that of ancient Earth when life was taking hold here," Melissa Trainer, an astrobiologist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, said in a statement. Trainer wasn't involved in either of the new papers, but she is the deputy principal investigator of NASA's Dragonfly mission that will launch to Titan in 2027 and arrive in 2034.

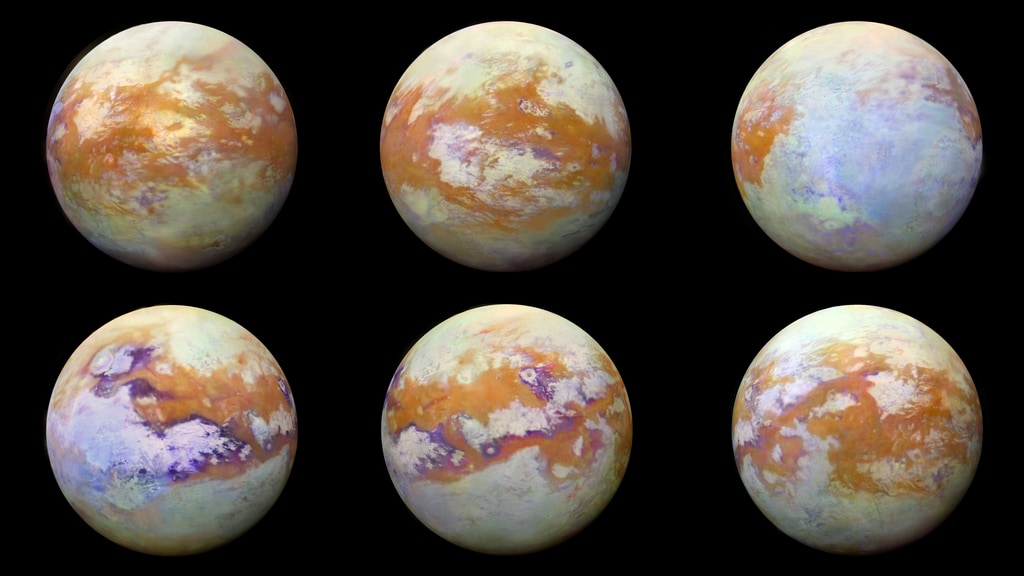

Related: Dazzling views show Saturn moon Titan's surface like never before

Scientists' fascination with the chemistry of Titan is what makes the new findings so intriguing. Researchers turned the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile toward the moon and spotted the chemical signature of cyclopropenylidene, an awkward triangular compound made of three carbon atoms and two hydrogen atoms.

"Titan is unique in our solar system," Conor Nixon, a planetary scientist at Goddard, said in the same statement. "It has proved to be a treasure trove of new molecules."

Cyclopropenylidene is only the newest of them. But finding it is surprising, the researchers say, because the little-known chemical is pretty friendly: if other compounds are near it, they tend to react, eliminating the cyclopropenylidene signature.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

So while scientists have found the compound in the universe, it's usually out in the vast, cold, near-empty areas between star systems — hardly an environment like that of Titan, although the chemical was only found in the moon's thinner upper atmosphere.

The newly spotted compound is also interesting because it is the second chemical found at Titan in which the carbon atoms lock in on each other to build a ring-like backbone. Other chemicals with that type of structure are crucial for the molecules that make up the information-containing part of DNA.

"The cyclic nature of them opens up this extra branch of chemistry that allows you to build these biologically important molecules," Alexander Thelen, a Goddard astrobiologist who worked on the research, said in the same statement. The researchers later checked archived data gathered by NASA's Cassini mission, which studied the Saturn system from 2004 to 2017, and saw supporting evidence for cyclopropenylidene in those observations.

Finding such a tantalizing compound in the upper atmosphere of Titan is particularly intriguing because scientists believe that sunlight-driven reactions in the area turn the simple compounds of Titan into increasingly complex, heavy molecules that eventually rain down onto the moon's surface.

The research is described in a paper published Oct. 15 in The Astronomical Journal.

Changing craters

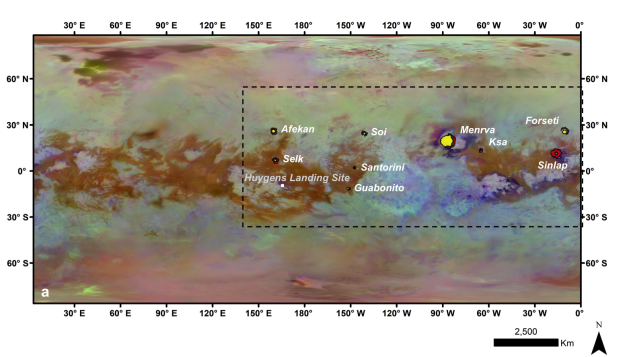

That surface is the site of the other recent finding about the strange moon, which arose when researchers studied Cassini data about nine major craters on Titan's surface.

First, they realized that these craters came in two different flavors, and that they were geographically separated. Around Titan's equator, the craters were located in dunes and contained exclusively organic material, then are sprinkled with sand. North and south of that region, craters were found on plains and included both water ice and organic material then doused in methane rain, carrying away any sand blown into them.

"The most exciting part of our results is that we found evidence of Titan's dynamic surface hidden in the craters, which has allowed us to infer one of the most complete stories of Titan's surface evolution scenario to date," Anezina Solomonidou, a research fellow at the European Space Agency and the lead author of the new study, said in a NASA statement. "Our analysis offers more evidence that Titan remains a dynamic world in the present day."

Among the sites the researchers studied was one called Selk, where the scientists found a crater covered by organic material, with no sign of methane rain. But Selk Crater has something special going for it — Dragonfly is already scheduled to visit the crater and scout it out, which should give scientists an even better view of what's happening on Titan's surface.

The research is described in a paper published Sept. 1 in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.