What's left of the 2024 solar eclipse lives in our hearts

Strangers watching a solar eclipse aren't really strangers at all.

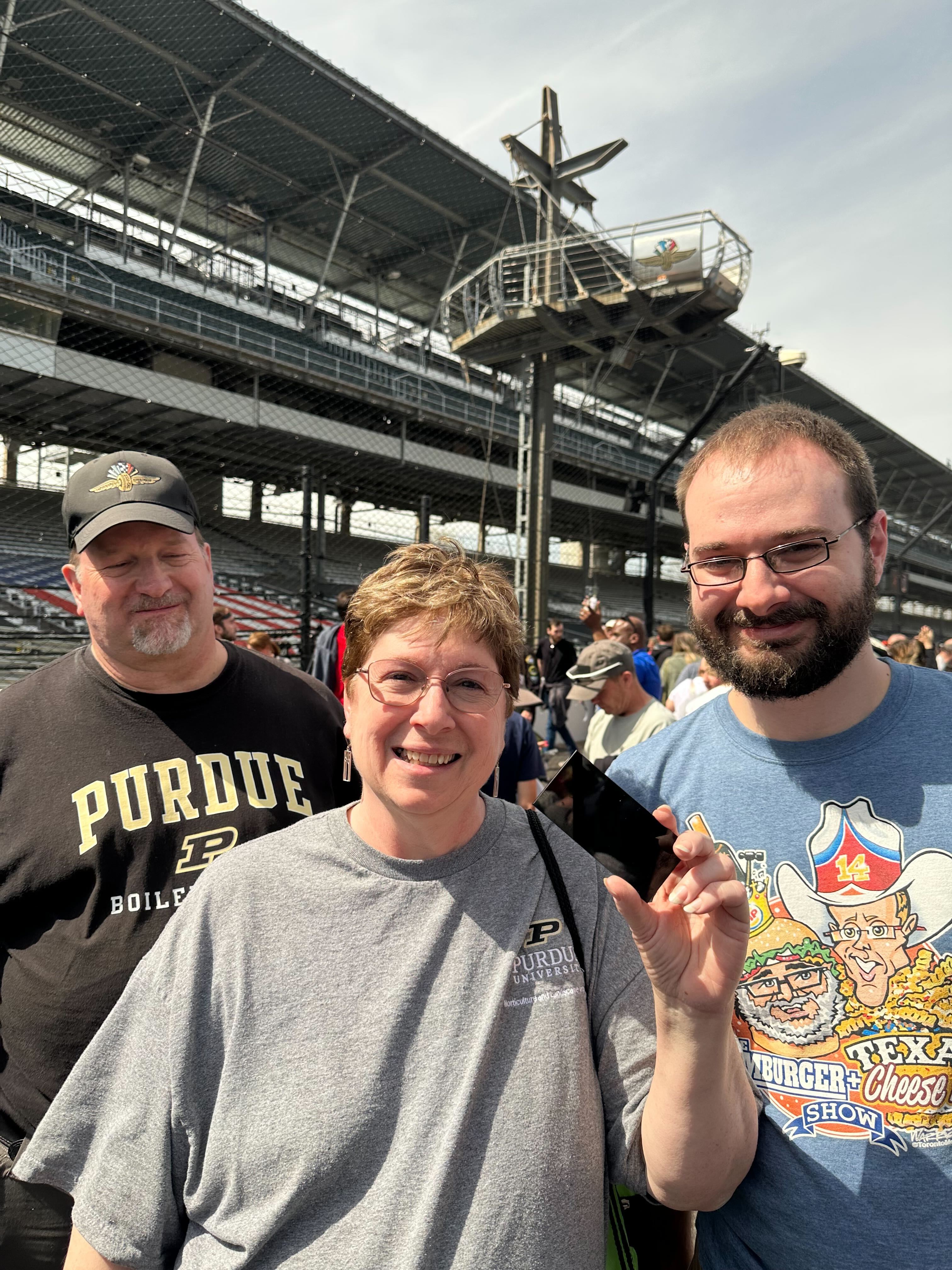

For a few moments this year, the sun was a lime green portal for Vicki Stirm. It happened while she was standing among tens of thousands of people on an asphalt racetrack in Indiana, on the same day our moon briefly stopped our star from illuminating our world.

The ocean of onlookers around her had been watching a total solar eclipse unfold through paper glasses shaped like what you might've gotten as a child before a 3D movie, similarly meant to prime the human eye for a new layer of vision — in this case, a painless view of a shrinking orange sun. But Stirm didn't need paper glasses.

Related: My formal 2024 solar eclipse apology

Among the crowd, she watched the sky through a palm-sized, iridescent black rectangle cut from the glass of a welding helmet, a tool that tinted the sun green as Earth's star mimicked a waning moon. It had belonged to her father, with whom she'd chased eclipses throughout her life, and who passed away in 2007. His name was Richard Ebert. "I just started crying," she said after totality was complete. "It was so beautiful. I was thinking of my dad, and when I was young."

Right beside Stirm was her son, Brenton. He'd traveled from Ohio to be there.

"Being a huge racing fan, you get two kinds of chills," he said. "Temperature chills, obviously, and then the chills of being at a sacred place like this at nighttime."

We were all still nestled on the Indiana Motor Speedway track, even though totality was over and the moon began allowing sunlight to warm us once more, bringing our planet back to cosmic normalcy. Constructed over a century ago, this track is where legendary racers have driven the iconic Indy 500 time and again, where old film directors once sourced inspiration, and where the accomplished driver Ed Carpenter had just finished performing some test laps that sounded like they broke the sound barrier, much to our delight.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Several meters from Stirm's family, with the sun still in a partial eclipse phase, Colin Kulpa and Cate Charron were perched on the edge of one of the track's white barriers. They weren't watching the sun when I saw them; they were watching the groups and stragglers who took it upon themselves to wander the track post-totality, periodically pausing to check on our star like it was a ball of focaccia baking in the oven. I was one of those stragglers.

"You hear about it, right?" Kulpa said of the few precious moments of totality. "But you have to experience it. You have to see it with your own eyes."

At first, Charron said she felt that experience in her heart. The sensation quickly moved into her mind, however. As a journalist herself who had covered the eclipse, she realized she couldn't help but fixate on some of the brilliant physical aspects of what she saw. "I thought it was going to be more yellow," she said of the glowing white halo that marked the moon's total eclipse of the sun. It was a halo that signified the sun's outer atmosphere, the corona, and one that could suddenly be seen with your own, unaided eyes, as Kulpa touched on. No paper glasses necessary.

"I'm surprised more people didn't cry," Charron continued. "It was also cool to be like, 'Oh my god, look at the moon,' and then to be with someone that I love." She lay her head on Kulpa's shoulder on cue with the word "love." Four hours before totality hit the speedway, Charron received a text message from her mother, who was in Toledo, Ohio, with a reminder of what's soon to come. In a way, Charron said, "we all get to experience the same thing."

"Technology just comes along and advances further; with every eclipse that happens, you're just going to be even more connected than before," Kulpa said.

Further down the track, And Agarwal, Fernando Barrios and Gabriel Costa were walking in the opposite direction as me (it was I who was on the wrong side, unfortunately). The three were students from Purdue University, about an hour's drive north of where they just witnessed a celestial event. Despite feeling awed by the glory of seeing the sun strangely darken alongside what appeared to be a solid block of humanity, Costa thinks it'd be worth catching the next total solar eclipse alone.

"I felt like I would enjoy it a little bit more if I was by myself," he said. "You can see, for example, the birds flying by, and you would hear the cicadas. For things like that, you would need to be more by yourself, and more isolated." It's a sentiment shared by many, myself included. I imagine seeing a total solar eclipse alone would make it feel like the eclipse is yours, and yours only.

Though Barrios agreed for a split second, he ultimately decided that the thrill of the event was enhanced through numbers. "Seeing the lights going out, everything going dark, the winds changing and the birds chirping," he said. "Being able to experience that with other people is a lot more fulfilling, in my opinion. It's so meaningful that we're all sharing the same thing."

Agarwal, in concurrence with Barrios, said he would particularly hope to see a total solar eclipse someday with family, because it is cosmic phenomena such as this that allow us to remember there are forces in the universe beyond our control: "I think there's value in that."

It was at this point that I did another one of my sudden pauses and looked at the sun again. Sure enough, it still looked like a clear tangerine circle with a perfect, curved slice removed. The eclipse would soon be over, though, and I felt worried I'd miss the ending. It seemed like something hugely consequential.

Outside the racetrack, most people were either occupied with starting their exit operations or taking pictures with NASA's blow-up Space Launch System moon rocket exhibit. If you looked closely, however, you'd find the Waldos with solar eclipse glasses on, still staring at the sky. I joined them until I felt like the sun had bounced back to its old self again.

My eyes had deceived me.

"There are two minutes left!" I heard someone shout next to me.

Deborah DeRuyver was trying to encourage her family to throw their solar eclipse glasses back on and finish the experience they'd driven hours to achieve. A secret member of this conversation, I put my glasses on as well. We sat silently until the end. "It's like a bookend," she said. "You're saying goodbye to it. I don't know if I'm going to be alive when there's the next one in America, or if we'd be able to get there, and my kids will be grown. It really is the last time I get to do something like this."

"I just think the universe is astonishing," DeRuyver gushed. "We live on such a beautiful planet."

Her son, 11-year-old Everett Tobocman, has fond memories of the last time they saw a total solar eclipse together in 2017, though there appear to be some key differences. First of all, he will remember this one far better. "I just remember a giant brick wall," Tobocman joked about his foggy 2017 recollections. This one seemed to be brighter than the last, he also believes, but he was most surprised about how powerful the sun actually is.

Even when the eclipse had turned our host star into a tiny sliver, he said, there was still enough sunlight passing through to hurt our eyes. In terms of taking the glasses off, it was simply "very weird." On the horizon, "it was like a giant sunset," he said.

His twin sister Piper had similar thoughts. As to her favorite part, it was "definitely the corona after taking my glasses off," she said. There are two phrases to sum up totality for her: Pure happiness and a connection to humanity. "You get to share the excitement with everyone, instead of keeping it all to yourself," she said.

"There was also just a sense of accomplishment," their father, Dan Tobocman, chimed in. "We made it here." During totality, he said he was pleased at how long a few minutes of anticipated darkness and an onyx hole standing where our sun should be seemed to last. "It was there, and I could enjoy it, then I could give everybody a hug and kiss," he said. "And then it was still there."

The entirety of his family's total solar eclipse journey is part of a longer story for him, in which he's able to recontextualize how to grapple with the often scary notion that humans are small, serendipitous accidents in an endless universe. It's about "the vastness of space and feeling lost," he explained. "But I've lived with that for decades now, I'm in my 50s, so now it's about sharing it with other people."

I can only speak personally on this, but I think watching our moon totally eclipse our sun does not feel like watching the moon, or the sun. It feels like watching an undisclosed third thing hang in the sky, a thing that seems like it's supposed to be hidden. I've often wondered what it would be like if I could swap eyes with the James Webb Space Telescope for a day and gaze into a nebula stretched across space, or what it might be like to dive across a black hole's event horizon, even if it meant I would be crossing the point of no return. I think I just deeply wish to witness a cosmic object I'm not normalized to.

Baby blue skies we cannot see beyond, floating cotton clouds that look like forbidden snacks and a star so formidable no one can stare at it directly without burning their eyes are somehow parts of daily life. A total solar eclipse fulfilled this desire of mine, to see something completely new in the natural universe, and it is this desire I don't think I need to speak on personally. It's one I now know I share with many, and one they share with each other. In a way, everyone who was at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway on April 8 is now linked. We aren't exactly strangers, though we may never meet.

Just when totality occurred, someone standing next to me, who I later learned was Adam Hafwz, a traveler from Dubai who came to the States to watch the eclipse, started yelling "bro, look at the sky!" Barely a couple of minutes before, we had been having a standard conversation about solar eclipse glasses safety. It was an excruciatingly normal moment to precede the excruciatingly intense one we found ourselves in next. And, he wasn't alone in his euphoria. Everyone had been screaming in joy. I even forced myself to fight my introversion and make a little "whoop" so I could be part of the club. It felt like indoctrination, and it solidified that, maybe for just a moment, we were all thinking the same thing — that we were watching something truly special, existential and important together.

"It's quite a mesmerizing experience," Hafwz said. "I would do it all over again."

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Monisha Ravisetti is Space.com's Astronomy Editor. She covers black holes, star explosions, gravitational waves, exoplanet discoveries and other enigmas hidden across the fabric of space and time. Previously, she was a science writer at CNET, and before that, reported for The Academic Times. Prior to becoming a writer, she was an immunology researcher at Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York. She graduated from New York University in 2018 with a B.A. in philosophy, physics and chemistry. She spends too much time playing online chess. Her favorite planet is Earth.