1st commercial astronomy spacecraft Twinkle set for launch in 2024

With Twinkle, astronomy will finally enter the new space age.

The world's first commercial astronomy mission, Twinkle, is gaining traction among exoplanet researchers as it takes steps toward launch in 2024 with funding secured to commence satellite construction early next year.

In 2014, when University College London (UCL) astronomy postdoc Marcell Tessenyi first entertained the idea to develop the world's first commercial astronomy mission, he knew he would have to overcome a lot of resistance. For decades, government-funded space agencies like NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) were in charge of expensive space telescope projects that took decades to develop and cost billions of dollars.

The model didn't always work well for the scientific community, but it was all they knew. Seven years later, the private exoplanet-watcher Twinkle is backed by more than 10 universities from all over the world, has received ESA funding and will soon be built by the European aerospace giant Airbus.

Related: Exoplanets: Worlds beyond our solar system

Lack of tools to study exoplanets

For Tessenyi, exoplanets were love at first sight. But when he decided to pursue this interest during his Ph.D. in astronomy at UCL, he found that the study of the strange worlds orbiting distant stars was marred with obstacles. NASA's Kepler Space Telescope was frequently in the news back then, discovering hundreds of new exoplanets, but there was no convenient tool that would make it possible to learn more about them.

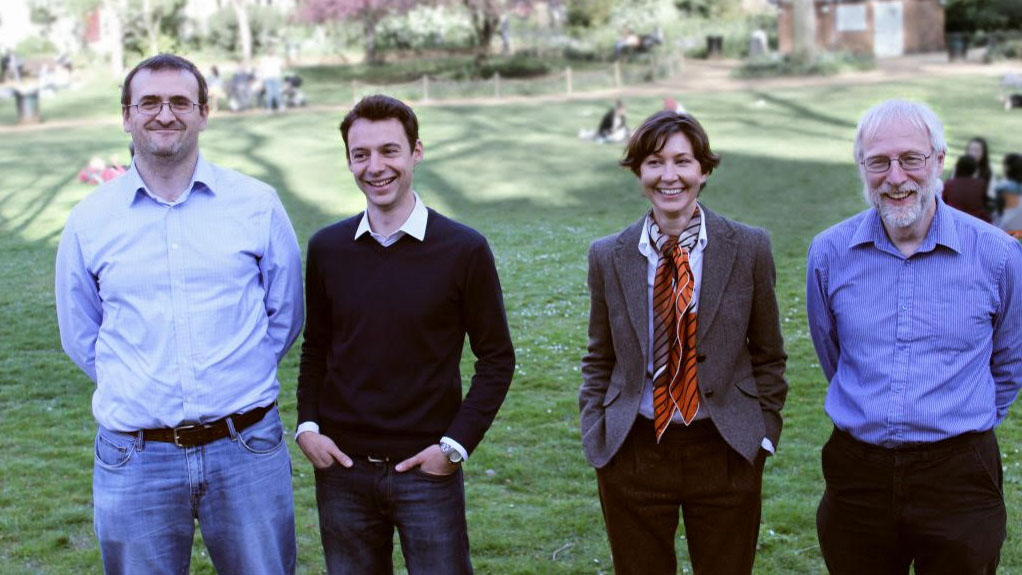

Frustrated with the lack of progress in the field, and also disappointed when in 2014 ESA turned down a UCL proposal for a new exoplanet mission, Tessenyi approached his supervisors Jonathan Tennyson and Giovanna Tinneti with an idea to do space missions differently — like a business.

"My Ph.D. was on understanding what are the technical requirements needed for satellites to be able to observe in a comprehensive manner exoplanet atmospheres so that we can start building a real understanding of what these planets are made of," Tessenyi told Space.com. "At that time, there were only a few measurements that were carried out by the Hubble Space Telescope and the Spitzer Space Telescope, but there were all sorts of limitations in the data because these satellites were not built to do observations of exoplanets."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The problem with Hubble

Both the veteran Hubble and Spitzer, retired in January 2020, had been conceived before the first exoplanet was discovered in 1992. It was only thanks to clever technical hacks that astronomers managed to tweak the signal returning from these spacecraft to glean some information about those distant planets, Tessenyi added.

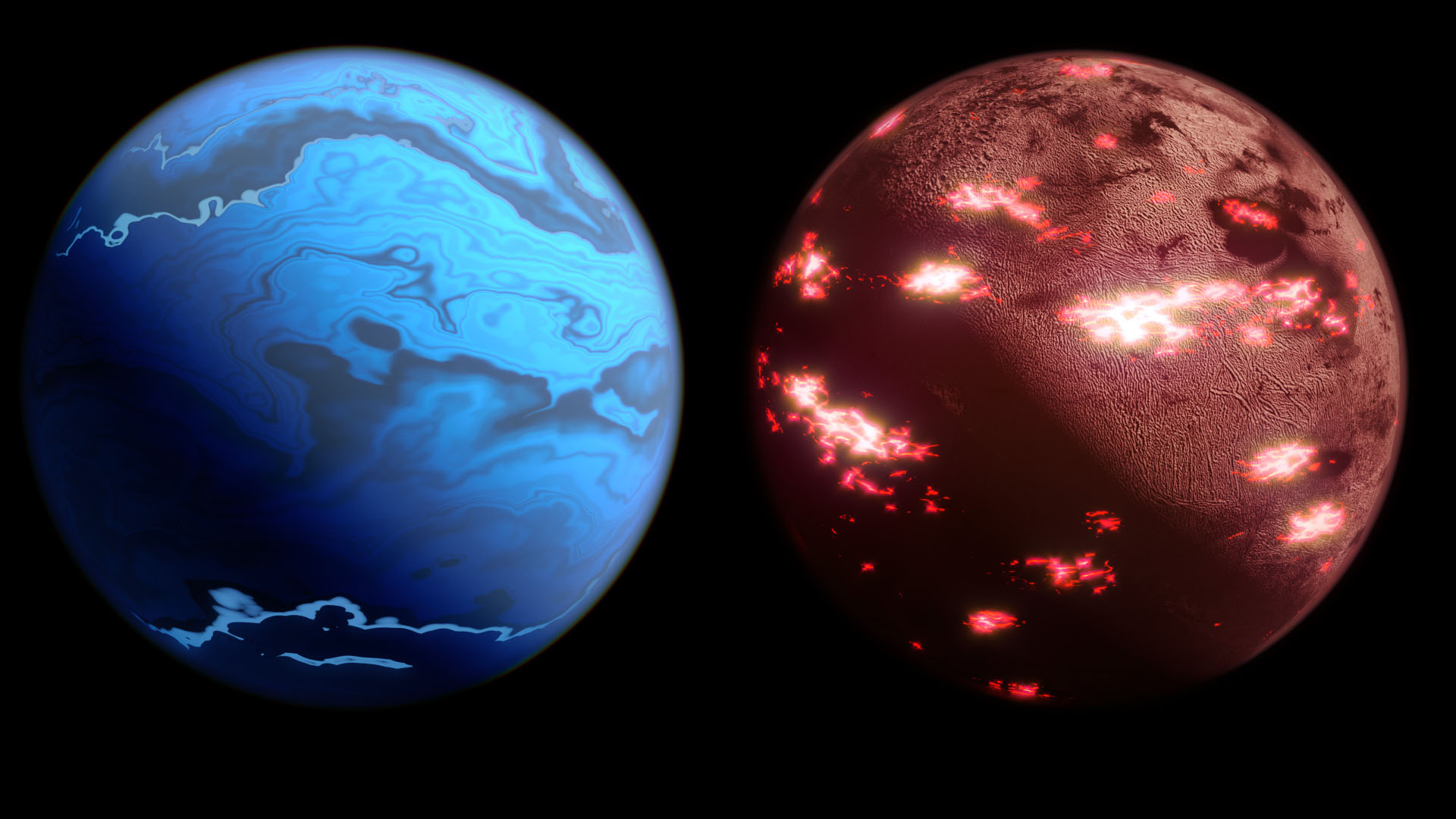

Nevertheless, the picture emerging from these scarce datasets was captivating: giant spheres of gas more than 3,600 degrees Fahrenheit (2,000 degrees Celsius) hot (since then nicknamed hot Jupiters), planets made of diamond, but also Earth-like planets that might harbor life. However, in addition to being scarce, the information was also incomplete, providing only the briefest glimpse into the nature of those mysterious worlds and leaving many questions open.

"Hubble can take spectroscopic measurements, which split light into different colors, when it looks at far-away targets," Tessenyi said. "That tells us something about the different types of chemical compounds in the atmosphere of the exoplanets. But Hubble can only do that for a limited range of wavelengths, so there is always uncertainty. We don't know for sure what we are looking at."

It wasn't just the gaps in the data that hampered the scientific progress but also the fact that the growing exoplanet community had to compete for time on Hubble (and Spitzer, too) with scientists studying all sorts of other astronomical phenomena. Still, Tessenyi said that the scientific community was initially reluctant to embrace the idea of Twinkle, the world's first privately funded astronomy mission based on the new-space ethos of fast development and low cost.

A new model for astronomy

"The technical and scientific aspects of this project were relatively easy," Tessenyi said. "The more difficult component was the skepticism that came from many different people in the community initially because it was an entirely new model."

Tessenyi decided to set up a company called Blue Skies Space with himself as a CEO and his former supervisors Tennyson and Tinneti on the board as a chairman and chief scientist. The start-up set out to attract funding from private backers with the goal to sell scientific data just like SpaceX sells rides to the space station or Planet sells Earth-observation images.

The UK small-satellite manufacturer Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd (SSTL) got on board early and helped to validate the mission design. Gradually, the skepticism of the scientists started to melt away.

"Over the years, we have spoken at various conferences and given lectures to hundreds of scientists," Richard Archer, who is responsible for partnerships development at Blue Skies Space, told Space.com. "Frequently, we see scientists from other fields, such as solar system science, being interested in the capabilities of our mission. They are interested in joining the project and helping us shape the mission."

Last year, Blue Skies Space signed up its 10th customer, a major milestone according to Tessenyi, and is looking to start welding metal in the first quarter of 2022.

At about 10% of the cost of an average space agency mission, the 770 lbs. (350 kilograms) Twinkle with its 20-inch (50 centimeters) telescope will be able to make spectroscopic measurements of exoplanets as accurately as the 31-year-old giant Hubble, according to Tessenyi. But the company already envisions a future beyond Twinkle.

"We are a commercial provider of a service for data," Tessenyi said. "Universities can buy a subscription to our satellites and access the data sets they would otherwise not be able to get. We will aim to recover the cost of the satellite, and if we are successful, to use the proceeds from satellite data sales to start co-funding the second generation of a satellite with a goal to deliver a whole series of satellites in the long-term."

Cheops, Plato, Ariel (and the others)

The appetite for Twinkle's data is, according to Tessenyi, not affected by the slew of new and upcoming exoplanet missions that have been announced in the past years. ESA's low-cost Cheops mission, for example, orbiting at the altitude of 430 miles (700 kilometers) just like Twinkle will, can only measure the basic characteristics of exoplanets such as their density and size.

The larger Plato, expected to launch two years after Twinkle, in 2026, will mostly look for rocky planets in habitable zones around large stars. Only Ariel, expected to launch at the earliest in 2029, will focus on exoplanet atmospheres, like Twinkle. James Webb Space Telescope, scheduled for launch later this year, will also contribute to exoplanet science.

"Twinkle and Ariel will be able to answer more complex questions," Tessenyi said. "Is there water in the atmosphere of the exoplanets? Is there carbon monoxide? With that we can start doing population studies, we can do comparative planetology between our solar system and the exciting planets that have been discovered outside."

In fact, Giovanna Tinneti, Tessenyi's former supervisor and Blue Skies Space chief scientist, is also a principal investigator on the Ariel mission.

"Ariel is a much larger and more expensive satellite that will be located in a more optimal orbit," Tessenyi said.

The Ariel mission will actually benefit from Twinkle, performing initial analysis of promising stars that could then be used to help Ariel focus on the most interesting targets.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.