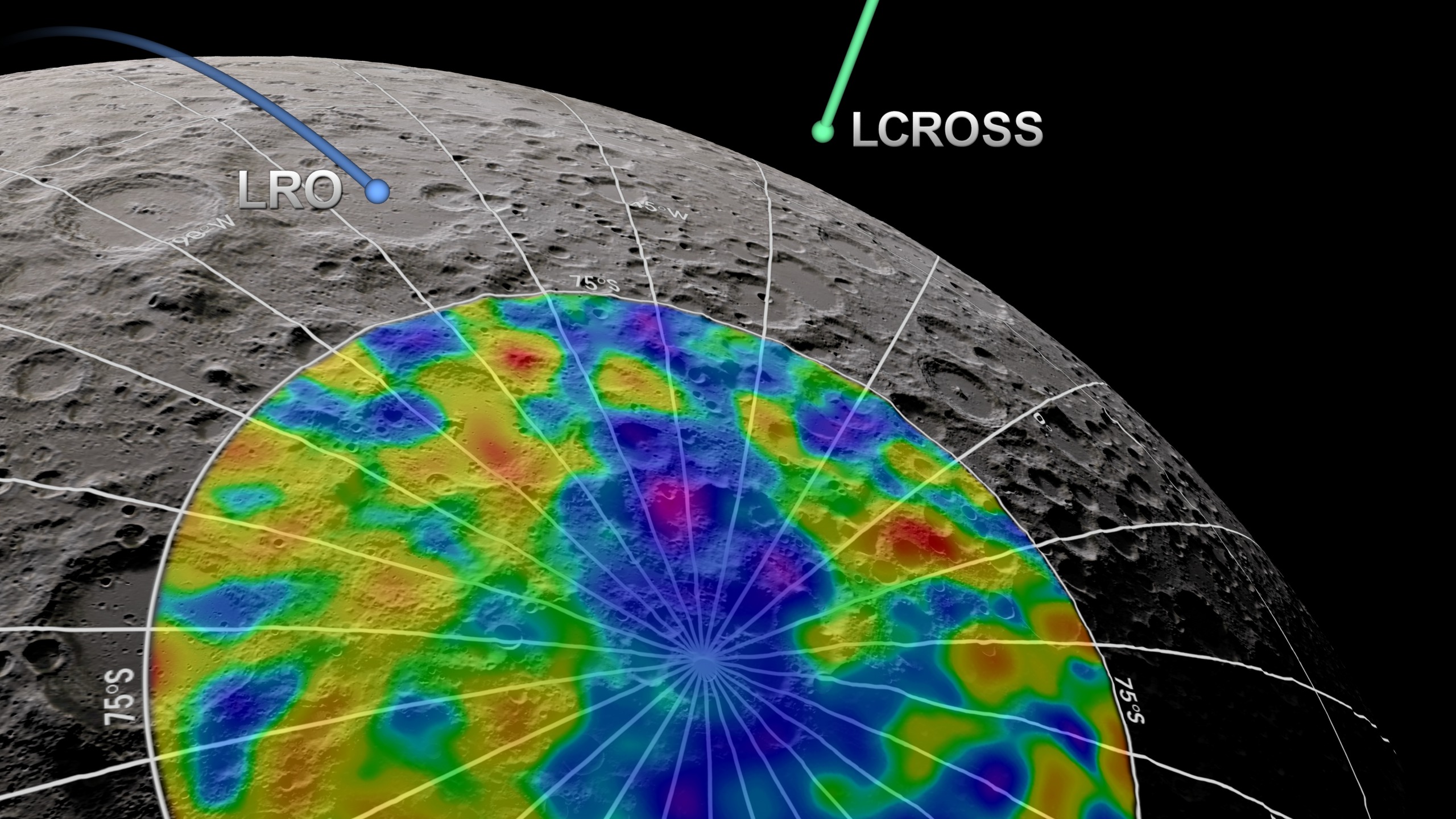

There's a simple reason that forthcoming NASA Artemis missions are slated to land around the moon's south pole: the area is thought to harbor lots of water ice.

Not only can humans theoretically drink that moon water, they can also split off its oxygen atoms to create breathable air. But first, astronauts will need a way to turn the ice into liquid water.

Finding a feasible way to do that is the goal of the Aqualunar Challenge. A collaboration between the U.K. and Canadian Space Agencies, the Challenge tasks teams from both countries to propose a way for future visitors to the moon to produce liquid water on the lunar surface. Now, the Challenge's organizers have announced the 10 U.K. finalists.

Their task is not a simple one. It takes a lot of work to turn lunar water ice into potable water, let alone separate it into hydrogen and oxygen. Not only is the water frozen rock-hard, it's likely riddled with lunar regolith that will turn into a gritty, unpalatable slurry when wet. Moon dwellers must not only melt the ice, they must also purify it.

Related: There's lots of water on the moon for astronauts. But is it safe to drink?

Each team's proposed tech must be able to survive the harsh cold and razor-sharp dust particles of the lunar south pole, while keeping mass as low as possible. Furthermore, especially with a task that could make the difference between life and death for astronaut explorers, their chosen method must be low maintenance.

"They cannot rely on components being sent up from Earth, and it won't be possible for astronauts to regularly change filters and tighten nuts and bolts," said UKSA reserve astronaut Meganne Christian in a statement.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Christian is also one of the judges tasked with evaluating the 10 British finalists, each of whom envisions a different approach.

Take Lunasonic, which would first melt the ice into water and purify it by blasting it with ultrasound waves, like a jewelry cleaner. Alternatively, the Regolith Ice Plasma Purifier for Lunar Exploration (RIPPLE) proposal would vaporize the ice, push it into a vortex and wick out pollutants like a salad spinner. Then there is the dramatically named Ganymede's Chalice, which would use mirrors to concentrate sunlight onto a crucible filled with ice, boiling away contaminants one after the other, leaving clean water at the end.

Over the next several months, the teams behind these three ideas, as well as seven others, will work on developing their technology with the aid of a £30,000 (about $38,500 US at current exchange rates) grant. Finally, in March 2025, organizers will announce a U.K. winner and two runners-up.

On the other side of the Atlantic, the organizers of Canada's competition announced eight semi-finalists. They'll be whittled down to four finalists in early 2025, with a final Canadian winner announced in early 2026.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Rahul Rao is a graduate of New York University's SHERP and a freelance science writer, regularly covering physics, space, and infrastructure. His work has appeared in Gizmodo, Popular Science, Inverse, IEEE Spectrum, and Continuum. He enjoys riding trains for fun, and he has seen every surviving episode of Doctor Who. He holds a masters degree in science writing from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program (SHERP) and earned a bachelors degree from Vanderbilt University, where he studied English and physics.

-

fj.torres "Keeping mass as low as possible" is possibly unnecessarily restrictive.Reply

Especially since the regolith will require sturdy processing materials.

At some point planners are going to have to accept the need for Starship class landers.