Ukrainian startup Promin Aerospace tests engine for new 'self-devouring' rocket

The company has been making progress despite the Russian invasion.

Olga Ozhogina is a Ukrainian space reporter, journalist and photojournalist. She contributed this article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights via the press center at Promin Aerospace, a Ukrainian rocket startup.

Despite the events unfolding in Ukraine, Ukrainian companies continue to work and develop space technologies. Promin Aerospace is one such company overcoming the unprecedented disruption to normal life.

Promin Aerospace has proven its concept over the past few months of a unique self-burning rocket, an idea based on autophagic, or "self-devouring," technology. The company has already conducted the first three experiments on the engine for its launch vehicle concept, which has allowed for improvements to the design as well as verified the viability of the central idea.

Related: Ukraine plans to join the EU. Will the nation's space prospects expand as a result?

Live updates: Russia's Ukraine invasion and space impacts

Promin Aerospace co-founder and CTO Vitaly Yemets proposed the core of the company's autophagic technology, which incorporates a hull consisting of solid fuel propellant for a single-stage rocket. The rocket burns itself up or "consumes itself" almost entirely during the duration of the flight, leaving next to no debris in space. Additionally, the rocket becomes more efficient as it climbs, consuming itself and reducing its mass.

The development of the autophagic engine is the first step in creating a complete launch vehicle that considers the issues of both space debris and rocket-part re-entry. These issues are becoming more prevalent as more rocket companies become operational. Promin Aerospace's engineers are currently conducting more tests on the engine to improve the design and begin work on the next stage of the autophagic rocket concept.

"Thanks to this series of experiments, we figured out what can be done better in the design of the engine and nozzle," Yemets said. "As a result, we increased the speed of gasification with a new gasifier printed on a 3D printer, proved the efficiency of the new oxidizer and eliminated burnouts."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

It would be impossible to make these improvements to the engine if the engineers didn't face internal challenges on each step of testing; these challenges gave clarity on what exactly in the construction design should be upgraded or changed. Below is a summary of each technical test conducted before and during the recent invasion.

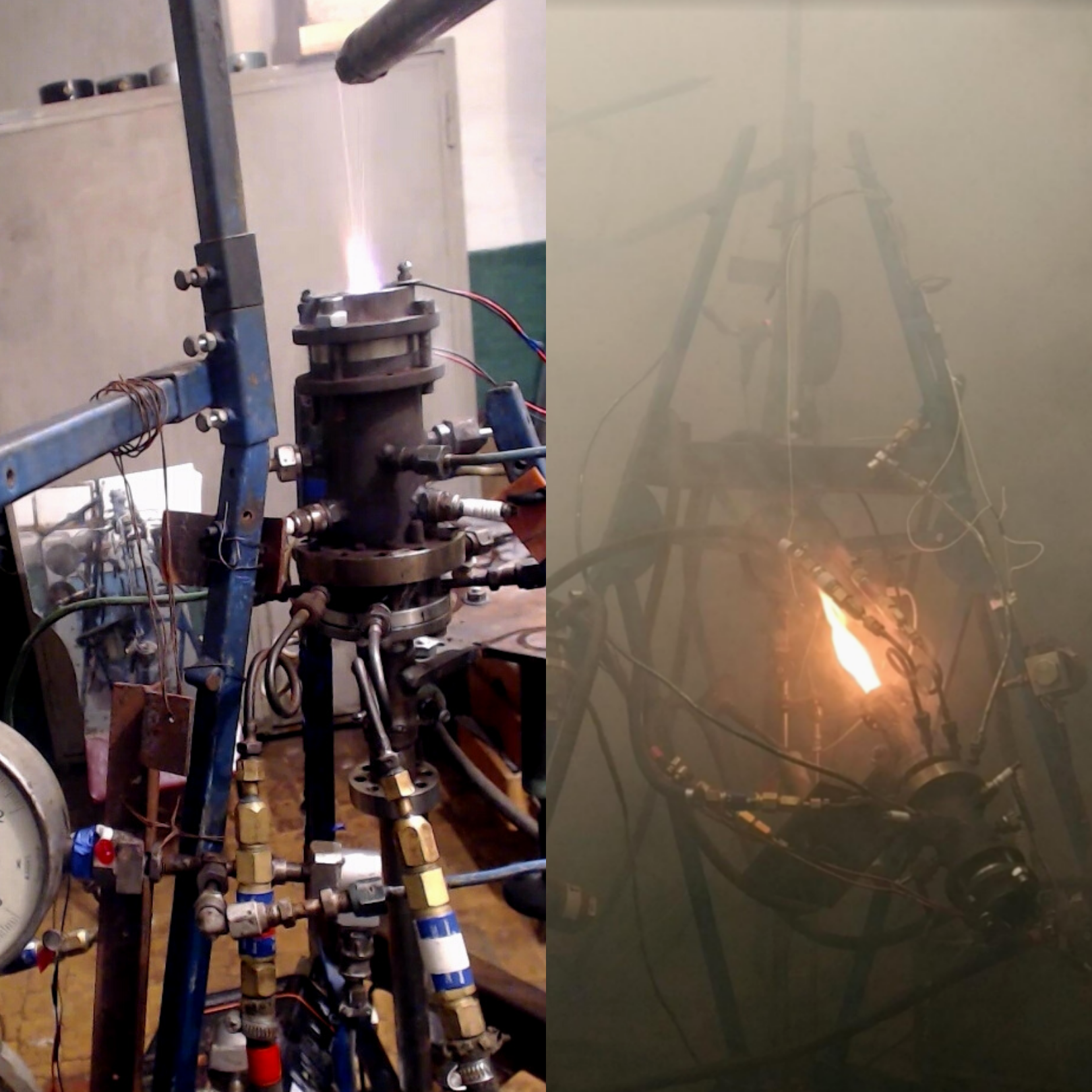

The first test: an aerospike nozzle and a new gasifier

During the recent experiment, tests were performed on a new gasifier in which a solid fuel rod is converted to gas and fed to the engine. This gasifier was built using 3D printing.

The new gasifier increased the rate of polymer conversion to gas two to three times compared to previous tests conducted with gasifiers made using traditional techniques. This was achieved due to the increased area of gasification, the complex surface obtained by laser printing.

The experiment lasted about 152 seconds. Gas fuel was used for the startup, and then solid fuel was stably fed to the gasifier using an experimental motor. The feed rate was 6 to 8 millimeters per second.

The engineers also conducted their very first test of an aerospike nozzle, which has a central body in the form of a truncated cone inside. The first experiment gave a surprising result — prolonged stable combustion.

However, 93 seconds into the experiment, burnout in the combustion chamber was witnessed. The burnout transpired due to the lack of experience with a new modification of the gasifier and the aerospike nozzle. The engineers have already developed new methods to control acceptable engine temperatures for the next experiment.

The second test: a modified engine

The next experiment the engineers conducted tested the enhanced modification of the engine. This time they put in multiple probes to monitor the temperature in numerous engine areas to prevent burnouts, as had happened in previous fire tests, and to understand the details of heat flow during testing. Additionally, understanding the temperature field of the current modification provides an essential understanding of the actual processes happening inside the steel combustion chamber.

The propellant rod was fed into the gasifier, and firing parameters were recorded with multiple sensors. Combustion of the solid propellant rod, consisting of coaxial layers of oxidizers and polymer as a fuel, was achieved. The combustion performance remained stable for almost 50 seconds, with a measured feed rate of 1 millimeter per second.

Interestingly, the disassembly and inspection after the test revealed some unexpected details. There was a minor uncontrolled explosion during the firing, although it did not cause the test to be aborted.

In subsequent tests, the starter gas was replaced with a safer mixture to prevent this from happening.

Related: The history of rockets

The third test: a new oxidizer and a bell-shaped nozzle

Promin Aerospace's engineers tested performance with a new oxidizer for the third experiment on the enhanced engine. Additionally, a different, bell-shaped nozzle was attached and utilized. As with the previous experiment, there were multiple probes monitoring the temperature in numerous engine areas to understand heat flow during testing and to help prevent burnout, as well as pressure gauges in both the combustion chamber and the pneumatic cylinder.

Following previous experiments, the engineers fed the propellant rod into the gasifier while recording the firing parameters with multiple sensors. No issues to achieve combustion were found with the new oxidizer. Compared to the previous experiment (which remained stable for almost 50 seconds, with a measured feed rate of 1 mm/s), the combustion performance was distinctly more stable and efficient; the experiment remained stable for 268 seconds at a rate of 7 mm/s.

The experiment ran for 277 seconds, including the preheating stage. However, at 268 seconds, an uncontrolled explosion caused the construction to be destroyed. After disassembly, it was apparent that the cones of the gasifier had burned out, which could have caused the oxidizer to become super-heated. Up until that point in the experiment, the pressure and performance of the fuel were stable, suggesting that the new oxidizer is incredibly efficient.

For the next test, a gasifier control will be utilized to ensure that the oxidizer does not become overheated. Additionally, more accurate temperature sensors will be used, and a fuel-oxidizer barrier must be designed to avoid damage to the engine in an uncontrolled explosion. Overall, in combination with the 3D printed gasifier, the oxidizer worked very well – it significantly increased the efficiency.

Once all experiments on the engine have been completed, Promin Aerospace plans to hold a suborbital trial launch this November and a commercial suborbital launch in early 2023. Promin Aerospace intends to begin work on orbital launches after concluding suborbital tests.

Promin Aerospace is based in Kyiv and Dnipro. Although Russia amplified its invasion in February, Promin Aerospace has been able to continue the development of its autophagic rocket concept while its employees juggle territorial defense.

"It is incredibly important for companies with high-tech developments to continue their work during the war," said Volodymyr Taftay, the head of the State Space Agency of Ukraine. "They are the future of our country and now support its economic front."

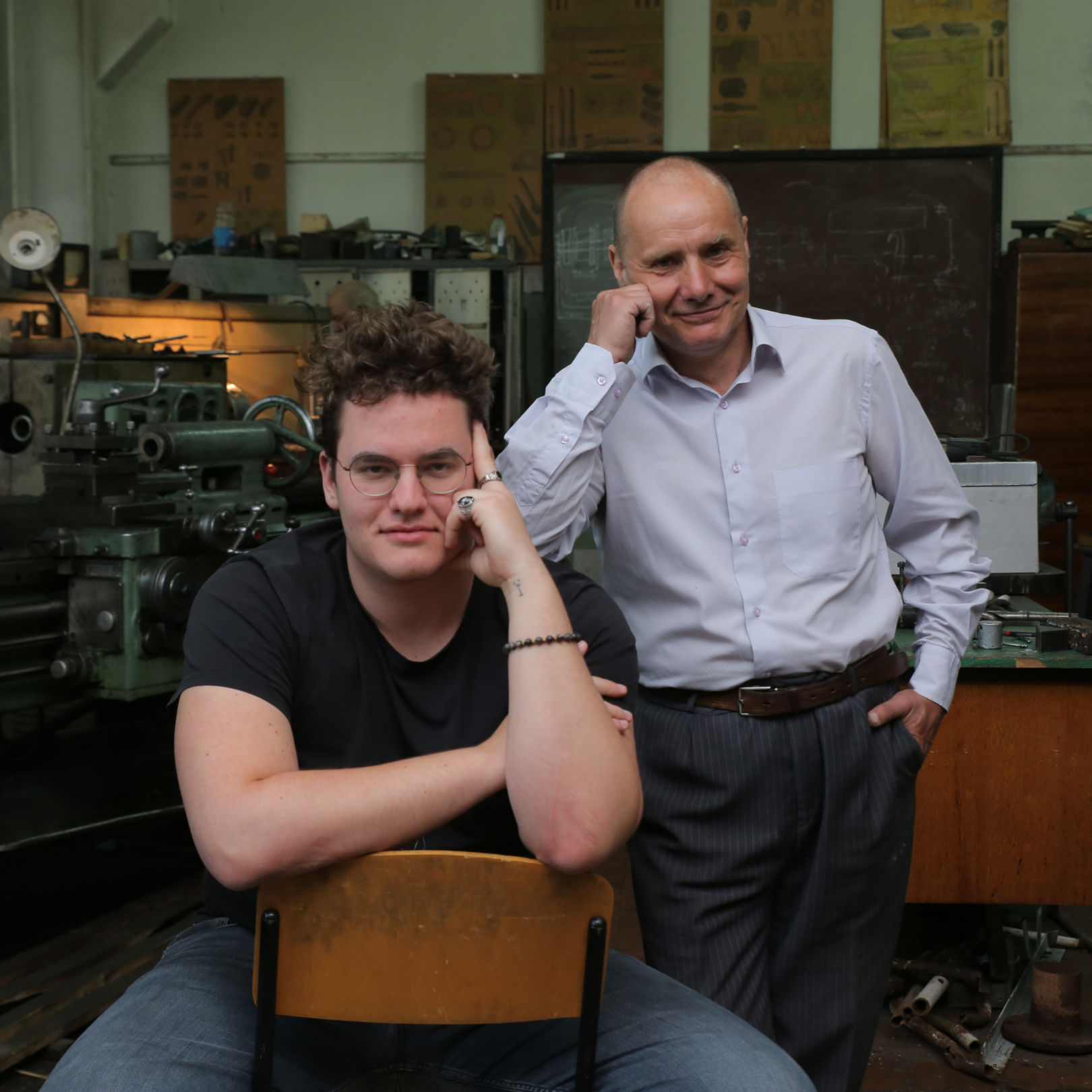

Promin Aerospace was established by Vitaliy Yemets and Misha Rudominski in 2021. It offers an entirely new technology for creating launch vehicles. This technology will make private launches available for any company, reducing their cost and preparation time while leaving no debris.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Olga Ozhogina is a Ukrainian space reporter, journalist and photojournalist. She studied avionics at the National Aviation University in Ukraine's capital, Kyiv, and journalism at Dnipro National University in Dnipro, the nation's famous "Space City." She brings considerable technical knowledge to her space coverage and has a broad range of experience across multiple platforms in news media.