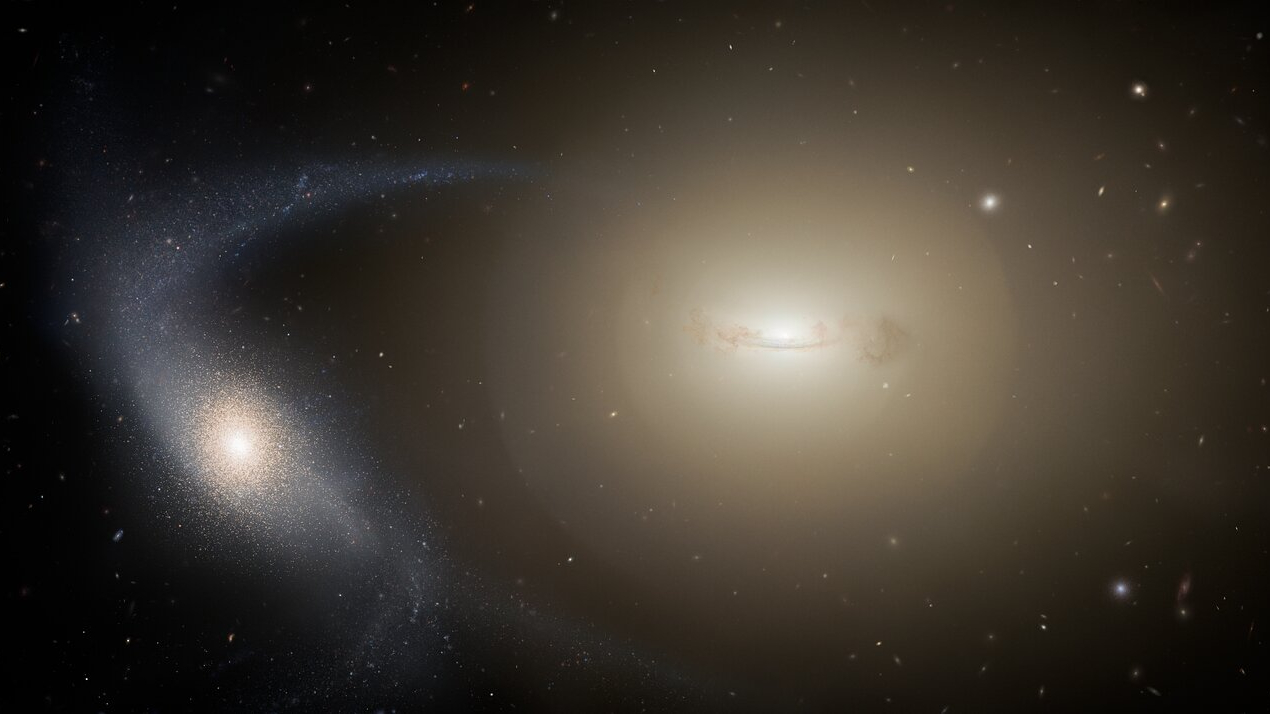

These small galaxies were shredded by their larger siblings — but they survived

The rare dwarf galaxies were likely victims of galactic cannibalism.

While galaxies appear to be lonely wanderers in the vast universe, many in fact huddle closely in clusters, held together by their collective gravity. And sometimes, it would appear, they also munch on one another.

In other words, larger galaxies in these pockets merge with and gobble smaller ones to grow even bigger — our own Milky Way galaxy actually cannibalized a small neighbor galaxy and gained supremacy about 10 billion years ago.

As for what happens to the smaller galaxies getting shredded by their massive counterparts? Well, while few disappear without a trace,, new research shows that some tiny galaxies are dense enough to power through. Those mighty realms are able to hold onto their cores and become what astronomers call Ultra Compact Dwarfs, or UCDs.

Related: Dark energy camera reveals galaxies caught in a cosmic 'tug of war' (photo)

Using the Gemini North Telescope located near the Mauna Kea mountain in Hawaii, the team behind the research spotted galactic cannibalism in action near the Virgo Cluster, a large grouping of thousands of galaxies relatively nearby to Earth. And in a first, the researchers found small galaxy victims transitioning into UCDs. As many as 106 galaxies exhibited far-reaching envelopes of stars, suggesting their outer layers were being ripped apart by nearby large galaxies. Meanwhile, however, tight groupings of stars in their centers reveal their gravitational grip is strong enough to survive the merger, astronomers say.

After stars and gas in the galaxies' outer layers are pried out in full, astronomers expect the tiny galaxies will come to represent late-stage UCDs.

"It's exciting that we can finally see this transformation in action," Eric Peng, an astronomer at National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory, said in a statement. "It tells us that many of these UCDs are visible fossil remnants of ancient dwarf galaxies in galaxy clusters, and our results suggest that there are likely many more low-mass remnants to be found."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Peng and his colleagues first spotted these candidate UCD progenitors in images taken by the Canada–France–Hawaii Telescope, also located near the summit of Hawaii's Mauna Kea mountain. However, in those images, it was very difficult to clearly distinguish the target galaxies from other faraway galaxies beyond the Virgo Cluster, according to the new study.

So, the team used Gemini North to perform follow up observations to accurately measure galaxy distances, then removed all background galaxies such that only the candidate UCDs within the Virgo Cluster could be seen.

The results showed these UCDs resided "almost exclusively near the largest galaxies," Kaixiang Wang, the study's lead author and a scientist at Peking University in China, said in the statement. "We immediately knew that environmental transformation had to be important."

This research is described in a paper published Wednesday (Nov. 8) in the journal Nature.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sharmila Kuthunur is a Seattle-based science journalist focusing on astronomy and space exploration. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She has earned a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social