NASA's Undersea Robot Crawls Beneath Antarctic Ice in Test for Icy Moons

It's going to take a lot more than a doggy paddle to explore the oceans hidden below the icy surfaces of some of the solar system's most intriguing moons.

That's why NASA engineers are already working on an underwater rover they hope could one day tackle the challenges posed by ocean worlds like Jupiter's moon Europa and Saturn's moon Enceladus. A team has been working on such a robot, called Buoyant Rover for Under-Ice Exploration or BRUIE, for a few years now. NASA is taking a prototype of that rover to Antarctica for testing in the most similar environment to those moons found on Earth.

"The ice shells covering these distant oceans serve as a window into the oceans below, and the chemistry of the ice could help feed life within those oceans," Kevin Hand, lead scientist on the BRUIE project at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, said in a statement. "Here on Earth, the ice covering our polar oceans serves a similar role, and our team is particularly interested in what is happening where the water meets the ice."

Related: The Weird Plumes of Jupiter's Moon Europa Are Spewing Water Vapor

The tests will take place at Australia's Casey research station along the coast of Antarctica far south of Australia, where BRUIE will spend a month exploring both the ocean and inland lakes. The rover focuses on where the top of the water meets the bottom of the ice.

"We've found that life often lives at interfaces, both the sea bottom and the ice-water interface at the top," Andy Klesh, lead engineer on the BRUIE project, said in the same statement. "Most submersibles have a challenging time investigating this area, as ocean currents might cause them to crash, or they would waste too much power maintaining position."

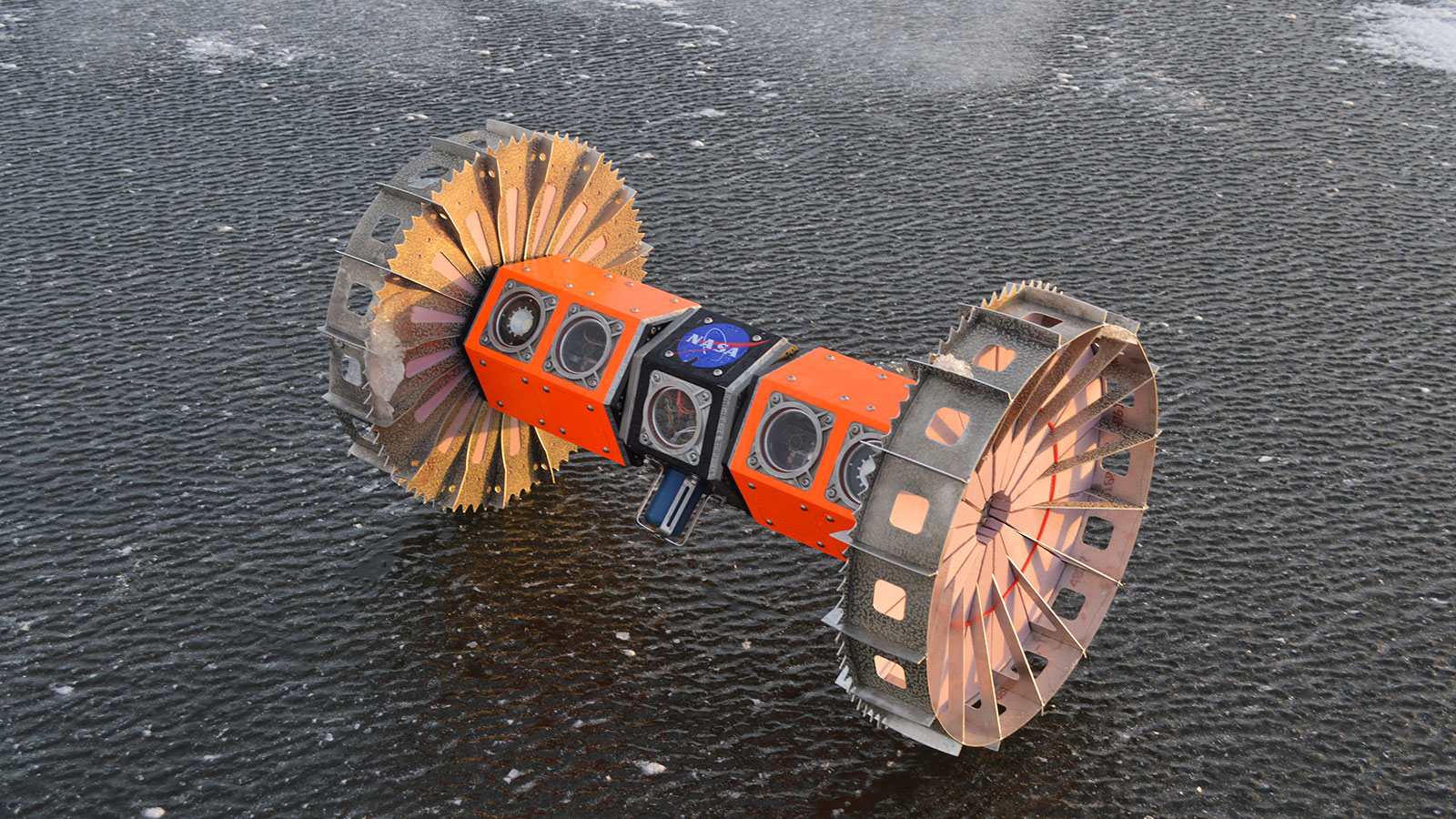

BRUIE is designed to manage these challenges via buoyancy; it crawls along the bottom of the ice, held up by the denser water below. The rover itself is a bar about 3 feet (1 meter) long, with a large wheel on each end.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

NASA's robot is also designed to turn itself on and off as needed between gathering measurements scientists are most interested in, which will let it stay locked below the ice for longer periods of time without recharging. With all these features, the team behind the project is hoping to eventually develop BRUIE into a flight model that can spend months at a time exploring below ice sheets that are from 6 to 12 miles (10 to 19 kilometers) thick, the sort of scenario a rover would need to survive on the distant moons NASA is targeting.

For early tests, BRUIE will explore on its own, tied to the ice to keep from getting lost. But in the long run, the rover is designed to do more than just rove; it will also carry instruments, including two cameras and probes measuring factors like salinity, water temperature and pressure, and oxygen levels, according to the statement. As data from BRUIE's first excursions come back, scientists will determine when to begin adding instruments to the tests.

But all the testing in the world can't prepare BRUIE for the biggest challenge of extraterrestrial exploration: recognizing potential signs of life that could look nothing like Earth's.

"We only really know how to detect life similar to that on Earth," Dan Berisford, a mechanical engineer on the project, said in the NASA statement. "So it's possible that very different microbes might be difficult to recognize."

- Photos: Europa, Mysterious Icy Moon of Jupiter

- An Algorithm May Be the 1st Thing to See Europa Clipper's Coolest Discoveries from Jupiter Moon

- On Icy Moons, Alien Life May Go with the Flow of Ocean Currents

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.