Are secret oceans hiding on the moons of Uranus?

Where might subsurface oceans lie in our solar system beyond moons like Europa and Enceladus?

The moons of Uranus could be sloshing with oceans hiding just below the surface.

Icy worlds speckle our solar system — from Jupiter's moon Europa to Saturn's moon Enceladus, scientists have been investigating these alien worlds, discovering subsurface oceans hidden under their icy crusts. Now, researchers have turned their gaze to the moons orbiting Uranus, searching for secret oceans.

In a new study not yet published, presented at the Dec. 15 AGU's Fall Meeting 2020, researchers led by Benjamin Weiss, a planetary scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, have developed a method for future missions to confirm the existence of subsurface oceans on worlds like the moons of Uranus. With this work, the team also hopes to further our understanding and knowledge of potentially habitable worlds.

"The big question here is, Where are habitable environments in the solar system?" Weiss said in a statement. Discovering subsurface oceans on Europa and Enceladus makes "a lot of us wonder whether there are many moons out there that, although they're small, may still be warm."

Related: Photos of Uranus, the tilted giant planet

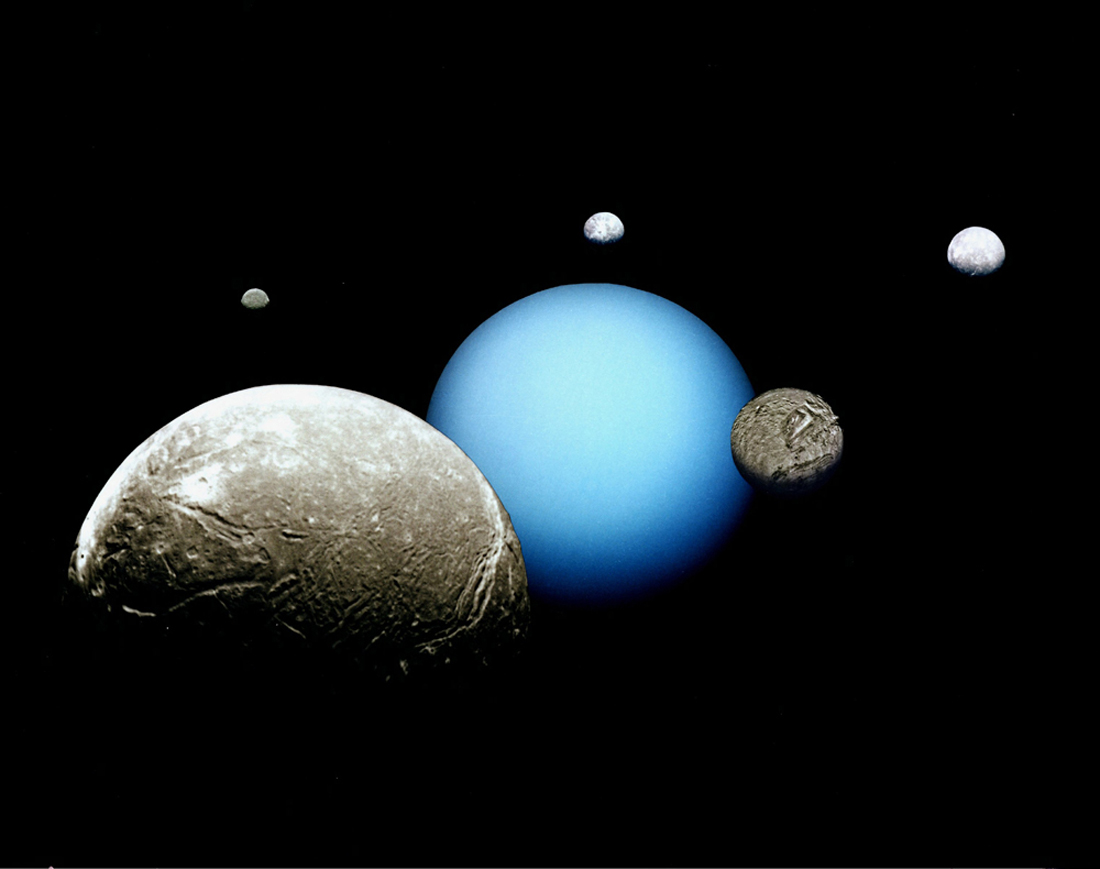

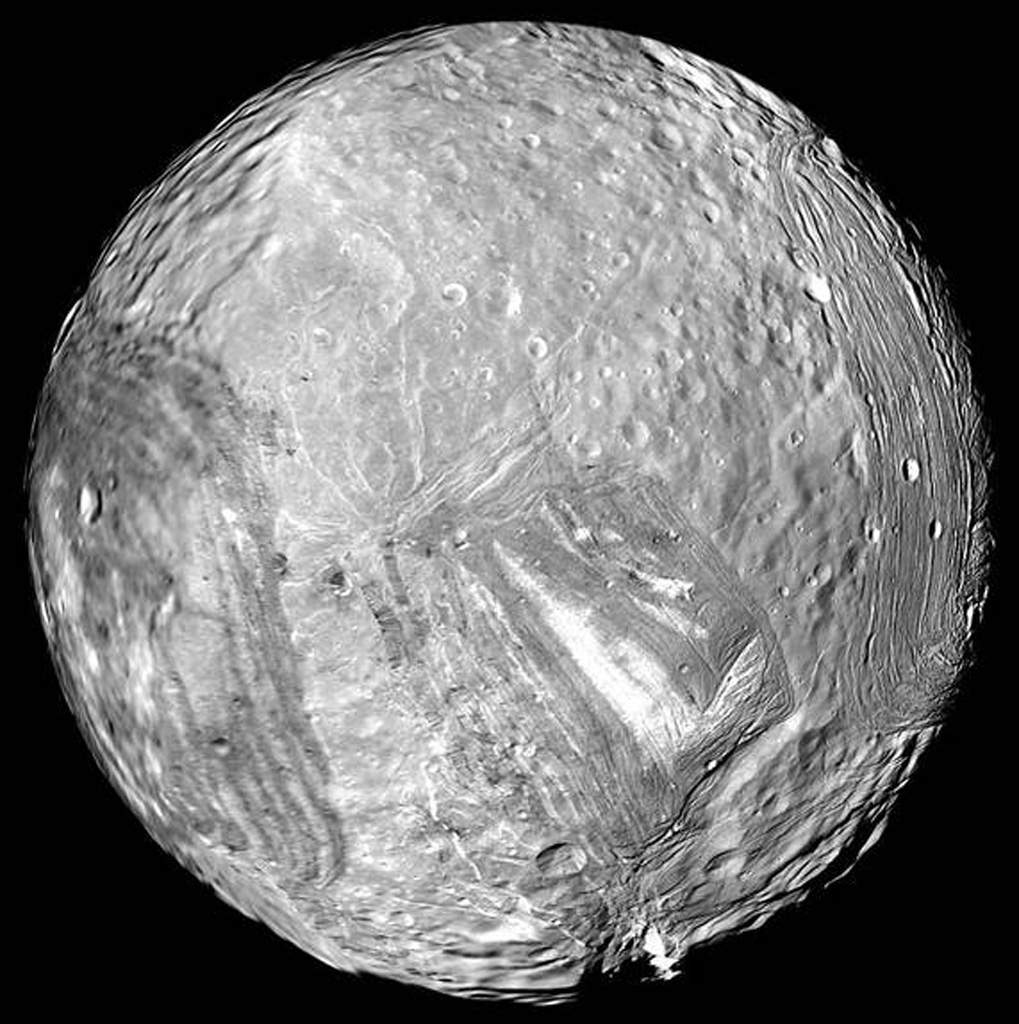

Uranus has 27 moons total, but the planet has five especially large moons — Titania, Oberon, Umbriel, Ariel and Miranda. When Voyager 2 swooped by the Uranus system back in 1986, it captured images that showed that these five big moons are made up of equal parts rock and ice and are heavily cratered. These images also showed physical signs of liquid water erupting through a world and freezing on its surface, called cryovolcanism.

The phenomenon could be caused by a subsurface ocean similar to what we see on Enceladus, which expels plumes from its ocean out into space.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

To determine whether a future spacecraft could definitively discover a subsurface ocean on one of these worlds, the researchers in this work calculated how strong the magnetic field Uranus would induce on a moon's ocean.

As a moon orbits a planet, that planet's magnetic field tugs at the moon, keeping it in its orbit. This tug from the magnetic field generates an electrical current that can create its own magnetic field, called an induced magnetic field. This induced field is thought to be created by a layer of some kind of electrically conductive fluid, like a subsurface ocean.

"If there’s liquid water there and it’s a little bit salty like ocean water on the Earth," Weiss said about Uranus' moons, "then it can be conducting, meaning currents can flow in it."

An induced magnetic field on one of these moons would look very different from Uranus' magnetic field to an instrument on a nearby spacecraft, making them observable from nearby.

In 1998, scientists used this same technique to confirm Europa's subsurface ocean and the ocean inside another of Jupiter's moons, Callisto. Europa's induced magnetic field was about 220 nanoteslas strong; Callisto's was about 40.

Instead of sending a spacecraft, Weiss and his team used theoretical models of Uranus' magnetic field to calculate the possible induced magnetic fields of the planet's five biggest moons. Miranda's induced magnetic field was determined to be the strongest, at 300 nanoteslas. While this does not confirm the presence of oceans on the worlds, Miranda, as well as Ariel, Umbriel and Titania, likely have induced magnetic fields strong enough to be detectable with existing spacecraft technology, according to Weiss in the statement.

Now, while subsurface oceans might exist on these moons, it's likely that they would be much farther beneath the worlds' surfaces than those on worlds orbiting Jupiter because Uranus' moons are colder so they'd likely have a thicker icy crust, David Stevenson, a planetary scientist at the California Institute of Technology, said in the same statement.

NASA doesn't have any current plans to send a probe to Uranus, however, the agency is considering a Neptune-bound mission called Trident that could gather information about Uranus as well, according to the statement; NASA will decide that mission's fate next year. However, a probe sent to look for these oceans would have to get really close to at least one of the planet's moons and such a mission likely won't happen until at least 2042, according to Stevenson.

Email Chelsea Gohd at cgohd@space.com or follow her on Twitter @chelsea_gohd. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Chelsea “Foxanne” Gohd joined Space.com in 2018 and is now a Senior Writer, writing about everything from climate change to planetary science and human spaceflight in both articles and on-camera in videos. With a degree in Public Health and biological sciences, Chelsea has written and worked for institutions including the American Museum of Natural History, Scientific American, Discover Magazine Blog, Astronomy Magazine and Live Science. When not writing, editing or filming something space-y, Chelsea "Foxanne" Gohd is writing music and performing as Foxanne, even launching a song to space in 2021 with Inspiration4. You can follow her on Twitter @chelsea_gohd and @foxannemusic.