Ursa Major Constellation: Everything you need to know about the Great Bear

Facts and myths about Ursa Major, the Great Bear constellation.

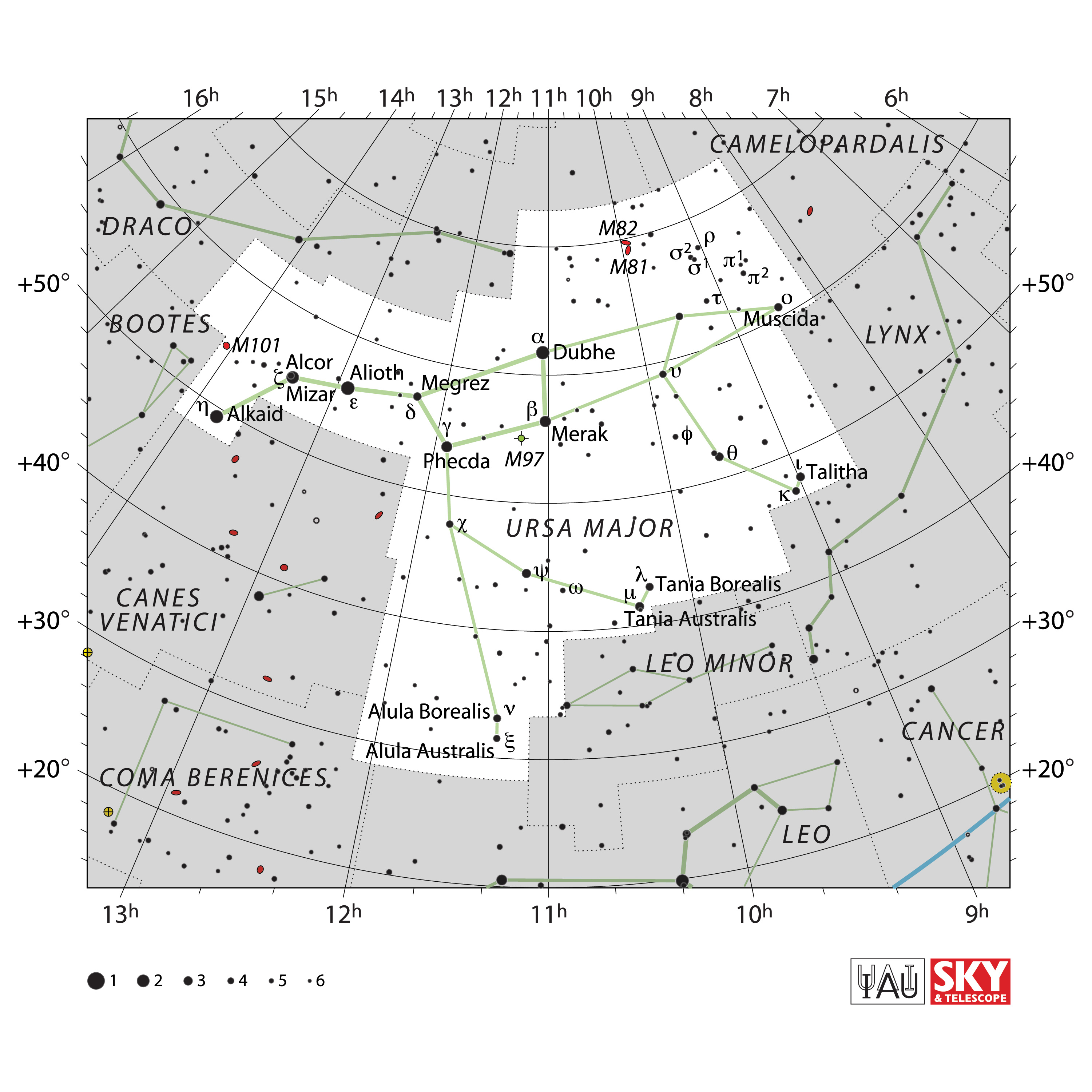

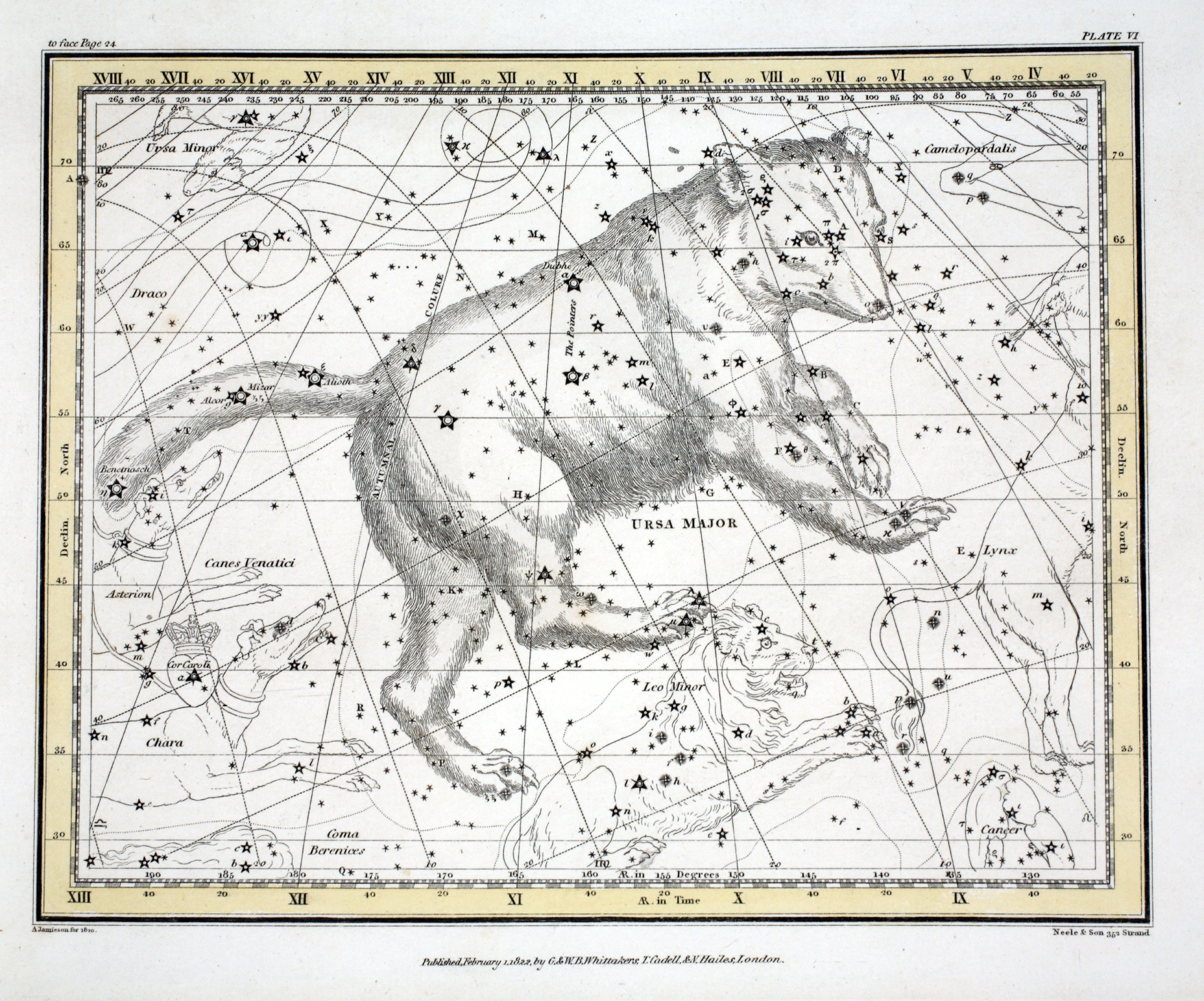

Ursa Major, also known as the Great Bear, is the third-largest constellation in the sky and the largest constellation in the Northern Hemisphere.

It includes the Big Dipper asterism and is one of the most recognizable collections of stars in the Northern Hemisphere.

We explore this infamous constellation in more detail and explore objects near the stars of Ursa Major that could make for an interesting skywatching target.

Related: Constellations of the western zodiac

Ursa Major FAQs answered by an expert

We asked Mindy Townsend, Dudley Astronomer at Siena College in upstate New York a few commonly asked questions about Ursa Major.

Mindy Townsend is an astronomer at Dudley Observatory, Siena College in upstate New York, U.S.

How can you find Ursa Major?

The first thing you want to do is look north. For me, the easiest part of Ursa Major to find is the Big Dipper. The constellation will be oriented differently depending on the time of night you look, but you can reference a star wheel, a free astronomy program like Stellarium, or any number of star-finding phone apps to determine the constellation's orientation.

When is the best time to view Ursa Major?

If you are in the Northern Hemisphere, you can see Ursa Major all year. This constellation is circumpolar, meaning that over the course of the night, it travels in a circle around the North Star and never sets. (You are not so lucky if you live in the Southern Hemisphere. The constellation is only partially visible there.)

What's the difference between Ursa Major and the Big Dipper?

The Big Dipper is what we call an asterism. It's basically just a pattern of bright stars that aren't official constellations. Sometimes these patterns are just part of a bigger constellation. In this case, the Big Dipper is part of the larger Ursa Major. The Big Dipper is the tail and back part of the body of Ursa Major.

Where is Ursa Major?

The constellation Ursa Major can be seen in its entirety from the Northern Hemisphere, in the second stellar quadrant. According to constellation-guide.com, over the course of a year, Ursa Major looks as if it were rotating around the north celestial pole, or the star Polaris.

Viewers in the Northern Hemisphere should look generally north to see the constellation, which skywatchers can spot most easily by looking for the Big Dipper (also known as the Plough, among other names).

Ursa Major observing targets

Astronomers have identified several other objects of interest near the stars of Ursa Major. For the best view of these objects, we recommend using binoculars or a telescope. If you need equipment, our best binoculars and best telescopes guides may help.

To find the objects of interest, it's helpful to know their magnitude, right ascension (RA) and declination (Dec).

Magnitude tells you how bright an object appears from Earth. The lower the magnitude, the brighter the object. For example, an object with a magnitude of -1 is brighter than one with a magnitude of +2.

Right ascension is to the sky what longitude is to the surface of Earth, corresponding to east and west directions. It's measured in hours, minutes and seconds.

Declination tells you how high an object will rise in the sky. Like Earth's latitude, declination measures north and south. Its units are degrees, arc minutes and arc seconds. There are 60 arc minutes in a degree and 60 arc seconds in an arc minute.

Bode's Galaxy (Messier 81)

Magnitude: 6.9

Approximate distance from Earth: 11.6 million light-years

Location: 9 hours, 55 minutes, 33.2 seconds (right ascension), +69° 3' 55" (declination)

Bode's Galaxy is among the brightest galaxies in the night sky. According to NASA, it was first discovered by German astronomer Johann Elert Bode in 1774 and was later reclassified by French astronomer Charles Messier in 1781. While the galaxy's arms are made up of mostly young blue stars formed in the past 600 million years, its center consists of older red stars and a black hole about 15 times more massive than the black hole at the center of the Milky Way.

Cigar Galaxy (Messier 82)

Magnitude: 8.4

Approximate distance from Earth: 12 million light-years

Location: 9 hours, 55 minutes, 52.2 seconds (right ascension), +69° 40' 47" (declination)

The Cigar Galaxy is near Bode's Galaxy; the two galaxies are likely visible in the same telescope, depending on its field of view. The Cigar Galaxy is remarkable for its star formation activity, with an extraordinary rate of star formation swelling its numbers in what NASA calls a "starburst." Eventually, the galaxy will run out of material and the starburst will subside. But for now, near the center of the galaxy, young stars are being born 10 times faster than in the Milky Way.

Pinwheel Galaxy (Messier 101)

Magnitude: 7.9

Approximate distance from Earth: 25 million light-years

Location: 14 hours, 3 minutes, 12.6 seconds (right ascension), +54° 20' 57" (declination)

The gigantic Pinwheel Galaxy contains at least 1 trillion stars, NASA estimates. The galaxy's spiral disk stretches 170,000 light-years across; for comparison, the Milky Way's vast collection of stars, gas clouds and dust is 105,700 light-years in diameter.

I Zwicky 18

Magnitude: 16.0

Approximate distance from Earth: 59 million light-years

Location: 9 hours, 34 minutes, 2 seconds (right ascension), +55° 14' 28" (declination)

The galaxy I Zwicky 18 was once thought to be the youngest galaxy ever observed, possibly forming as recently as 500 million years ago. But later research showed that it contained some very old stars and likely formed around the same time as other galaxies. According to the European Space Agency, astronomers now think that instead of being particularly youthful, the galaxy has had a notably slow rate of star formation, and they're not sure why.

Hubble Deep Field

Magnitude: n/a

Approximate distance from Earth: n/a

Location: 12 hours, 36 minutes, 49.4 seconds (right ascension), +62° 12' 58" (declination)

The first Hubble Deep Field is an area of space in the Ursa Major constellation, chosen because it appears relatively empty. In 1995, the Hubble Space Telescope took 342 images of the area, taking advantage of its "emptiness" to see farther away — and thus further back in time — than any telescope had before. In the end, according to NASA, the telescope imaged over 3,000 young galaxies too distant to be detected by other telescopes.

Ursa Major in world culture

The stars that make up the constellation Ursa Major were described as a "great bear" by ancient Greek astronomer Claudius Ptolemy in his classic studies of the night sky, and Greek myths tell the story of a nymph named Callisto who was transformed into a bear and hidden in the stars by Zeus, according to GreekMythology.com.

But the same stars have also been described and used for storytelling or navigation by many other groups and cultures. For example, according to the Swinburne University of Technology, Ursa Major was known to ancient Egyptians as an ox and ox handler, depicted in paintings found in the tomb of the pharaoh Seti I. And in ancient Chinese astronomy, the constellation depicts a celestial bureaucrat carried on a cloud.

The Mi'kmaq people, whose traditional lands are in the northeastern part of North America, also describe the stars in Ursa Major as a great bear (or Mother Bear, depending on the translation) and the hunters that pursued her, according to Digital Museums Canada. Other Native American peoples saw the same stars as loons, a canoe, wolves, bison, elk or caribou, according to Western Washington University.

Today, the stars in Ursa Major feature in Polynesian wayfinding, according to the Polynesian Voyaging Society. They are part of a group of stars called "The Seven," featured in master navigator Nainoa Thompson's second star line.

Additional resources

For kids and anyone who likes to get crafty, try this mobile-building activity from the American Museum of Natural History to see the stars of Ursa Major from all angles. Then, check out the rest of the galaxy with the Milky Way Explorer. If you want more stories about the constellations and their myths, read Ian Ridpath's "Star Tales" (Lutterworth Press, 1989).

Bibliography

Belleville, M. (2023, January 13). Discoveries — Hubble's deep fields. NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/content/discoveries-hubbles-deep-fields

Constellation Guide. (n.d.). Northern constellations. Retrieved February 14, 2023, from https://www.constellation-guide.com/constellation-map/northern-constellations/

Constellation Guide. (n.d.). Ursa major constellation: Stars, myth, facts, location. Retrieved February 14, 2023, from https://www.constellation-guide.com/constellation-list/ursa-major-constellation/

Digital Museums Canada. (n.d.). The Amerindian sky. Canada Under the Stars. Retrieved February 14, 2023, from http://astro-canada.ca/le_ciel_des_amerindiens-the_amerindian_sky-eng

European Space Agency. (2007, October 16). Hubble shows 'baby' galaxy is not so young after all. https://www.spacetelescope.org/news/heic0716/

Garner, R. (2017, October 19). Messier 81. NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/feature/goddard/2017/messier-81

Garner, R. (2017, October 19). Messier 82 (The cigar galaxy). NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/feature/goddard/2017/messier-82-the-cigar-galaxy

Garner, R. (2017, October 19). Messier 101 (The pinwheel galaxy). NASA. http://www.nasa.gov/feature/goddard/2017/messier-101-the-pinwheel-galaxy

GreekMythology.com. (2015, January 31). Callisto. https://www.greekmythology.com/Myths/The_Myths/Zeus's_Lovers/Callisto/callisto.html

Polynesian Wayfinding Society. (n.d.). Hawaiian Star Lines. Retrieved February 14, 2023, from https://www.hokulea.com/education-at-sea/polynesian-navigation/polynesian-non-instrument-wayfinding/hawaiian-star-lines/

Swinburne University of Technology. (n.d.). Constellation. Retrieved February 15, 2023, from https://astronomy.swin.edu.au/cosmos/c/Constellation

Western Washington University. (2022, March 2). Native American sky. https://www.wwu.edu/astro101/indiansky.shtml

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Vicky Stein is a science writer based in California. She has a bachelor's degree in ecology and evolutionary biology from Dartmouth College and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz (2018). Afterwards, she worked as a news assistant for PBS NewsHour, and now works as a freelancer covering anything from asteroids to zebras. Follow her most recent work (and most recent pictures of nudibranchs) on Twitter.