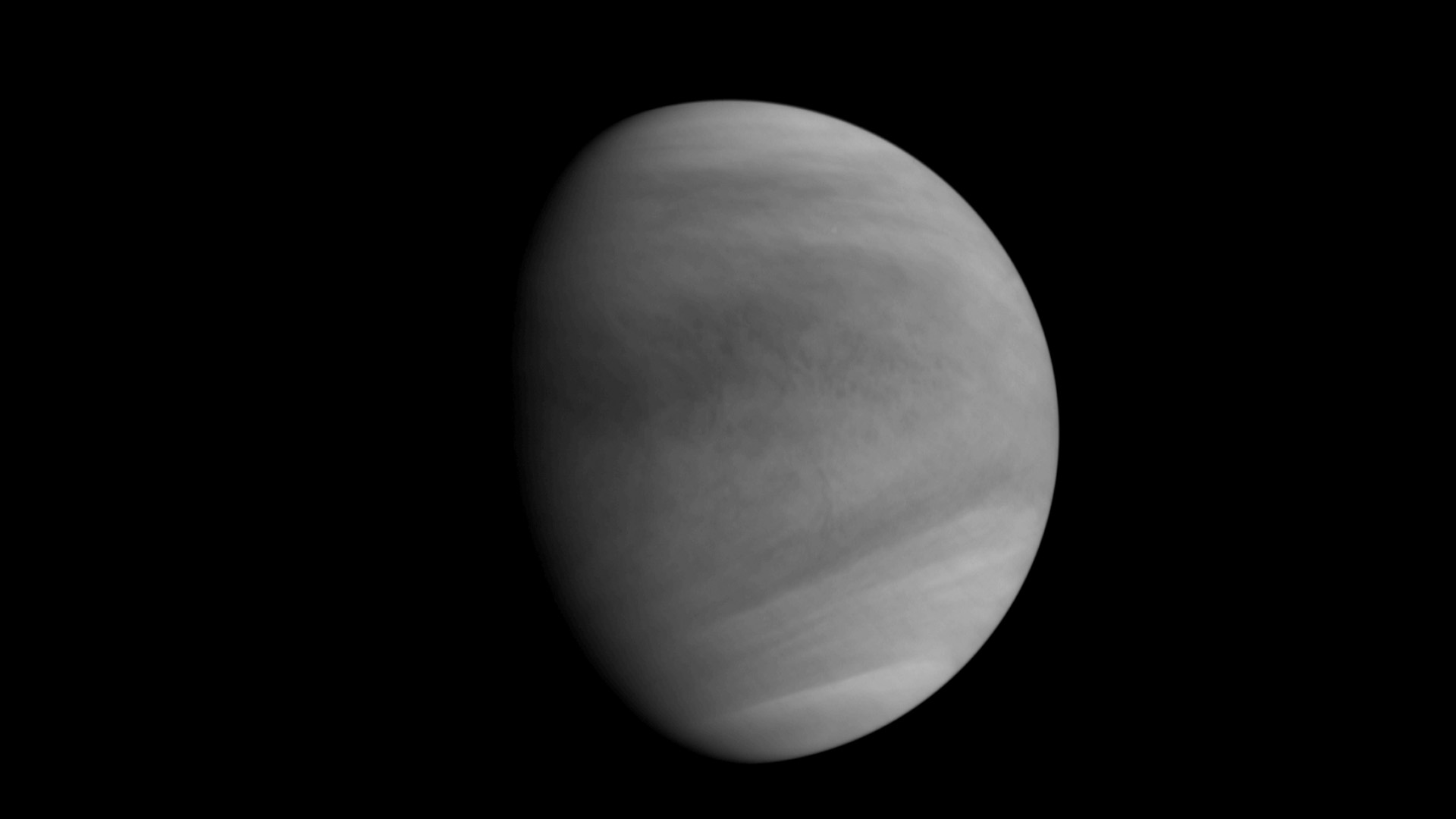

Why is a day on Venus longer than a year? The atmosphere may be to blame.

Venus' stormy atmosphere acts like a brake on its rotation.

Venus' dense and stormy atmosphere is the cause why a day on the scorching planet is longer than a year, a new study suggests.

Venus is a strange and inhospitable world. About as large as Earth, Venus orbits the sun at about two thirds of the distance between our planet and the star. Shrouded in a dense and toxic atmosphere of carbon dioxide and sulfuric acid, the planet suffers from a runaway greenhouse effect that pushes temperatures on its surface to life-preventing 900 degrees Fahrenheit (475 degrees Celsius). And something else is odd about this world: While Venus completes its orbit around the sun in 225 Earth days, it takes 243 Earth days for the planet to spin around its axis. That means that a year on Venus is shorter than a day!

A new study by University of California astrophysicist Stephen Kane now suggests that the thick and stormy Venus atmosphere might be the cause.

"We think of the atmosphere as a thin, almost separate layer on top of a planet that has minimal interaction with the solid planet," Kane said in a statement. "Venus' powerful atmosphere teaches us that it’s a much more integrated part of the planet that affects absolutely everything, even how fast the planet rotates."

Related: Scientists hail 'the decade of Venus' with 3 new missions on the way

Kane suggests that without the atmosphere, Venus's rotation would speed up to a rate that would match its orbit around the sun, a phenomenon known as tidal locking.

Tidally locked celestial bodies are under the gravitational influence of a much larger body. The gravity of the larger body keeps the rotational period of the smaller body in sync with its orbit around the larger body. That means the smaller body completes one rotation in exactly the same time as it completes one orbit: one year equals one day. As a result, a tidally locked body constantly faces its larger neighbor from the same side. Probably the best known example is Earth's moon.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Tidal locking happens over long periods of time. It may take millions of years for the year to fall in sync with the day.

To investigate why Venus' rotation is so slow, Kane first calculated how long it would take for a planet like Venus to get tidally locked. The calculation factored in the size of the two bodies, their mass, gravity and rotation rates.

He discovered that in fact, it only should have taken 6.5 million years for Venus to get tidally locked. That is only a small fraction of the 4.5 billion years for which the solar system exists.

Therefore there has to be a reason why Venus's rotation hasn't yet matched its orbit and Kane believes that the reason is the atmosphere.

"Extremely fast winds cause the atmosphere to drag along the surface of the planet as it circulates, slowing its rotation while also loosening the grip of the sun’s gravity," Kane said the statement.

Related: China may have its sights set on a mission to Venus

Paradoxically, the sun itself acts as a force enabling the atmosphere to brake against the tidal lock, Kane said.

"The gravity of the sun wants to tidally lock Venus, however, the energy from the sun is providing a lot of the driver in the Venusian atmosphere, which is preventing the tidal locking, because it's making the atmosphere much more dynamic," Kane told Space.com.

Uncovering the interactions between a planet's atmosphere and its effect on tidal locking may have implications that far surpass Venus.

As exoplanet hunters — such as the James Webb Telescope — stumble across new and exciting potentially habitable worlds, Kane argues that scientists should consider that some of them are experiencing tidal locking similarly to Venus.

"First of all, when we're looking at exoplanets, we want to make sure that we're able to distinguish between an Earth similar planet and a Venus similar planet and then we want to understand what the effect the atmosphere could be having on the planet and its rotation rate," Kane said.

Kane also points out that the current methods of exoplanet hunting are "indirect techniques" and researchers can't actually directly see them and "infer the existence of the planet from the effect that has on the star." These inferences come from models based on information gained from studying planets in our own solar system. Understanding as much as possible about near tidally locked planets, such as Venus, can help researchers to learn more about planets in other star systems that might potentially host life.

The study was published on April 20 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Scott is a staff writer for How It Works magazine and has previously written for other science and knowledge outlets, including BBC Wildlife magazine, World of Animals magazine, Space.com and All About History magazine. Scott has a masters in science and environmental journalism and a bachelor's degree in conservation biology degree from the University of Lincoln in the U.K. During his academic and professional career, Scott has participated in several animal conservation projects, including English bird surveys, wolf monitoring in Germany and leopard tracking in South Africa.