It has been a great run for the planet Venus. Going back to late November this dazzling world has dominated our western evening sky. It is a special planet: Earth's sister, coming nearest to us, very much alike in size, and perpetually covered by thick clouds that make it an excellent reflector of light. The dazzling, silvery white planet shines brighter for us than any other planet in the night sky. During late March and April, Venus soared high into the sky. For observers of north-temperate latitudes this was the highest evening appearance of its eight-year cycle. More on that later.

Also in early April, Venus glided through the southern fringe of the Pleiades star cluster, and toward the end of the month telescopes and steadily held binoculars showed it to be a narrowing crescent as Venus approached the Earth. It grew longer and more concave and as the resultant illuminated area continued to grow progressively larger, its brilliance grew even greater, reaching a pinnacle near the end of the month.

On May 4, Venus reached its greatest declination north (its greatest angular distance north of the celestial equator) in its eight-year cycle, and its greatest (27.82 degrees) until the year 2239. But ever since, Venus has been in a sort of "celestial freefall."

Related: Examining the phases of Venus

Venus not only has been growing wider and slimmer (and subsequently a bit dimmer), but it's now plunging sunward at more than a degree per day as it whirls toward us in space. By month's end it will be, to say the least, very challenging to see: only 2 degrees above the west-northwest horizon just 20 minutes after sunset.

But while Venus rapidly falls, another planet is coming into view and is rapidly ascending in the evening twilight sky: Mercury.

A rendezvous on Thursday night

This smallest and fastest-moving planet (only 1.4 times wider than our moon) orbits the sun just a little over four times per year (4.15 time to be precise), but from our moving viewpoint on Earth it appears to go around only 3.15 times. On average, each year it makes about 3.5 swings into the morning sky and as many into the evening. But each apparition into either the morning or evening sky is markedly different thanks to its very eccentric orbit and the various viewing angles from which we can see it.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

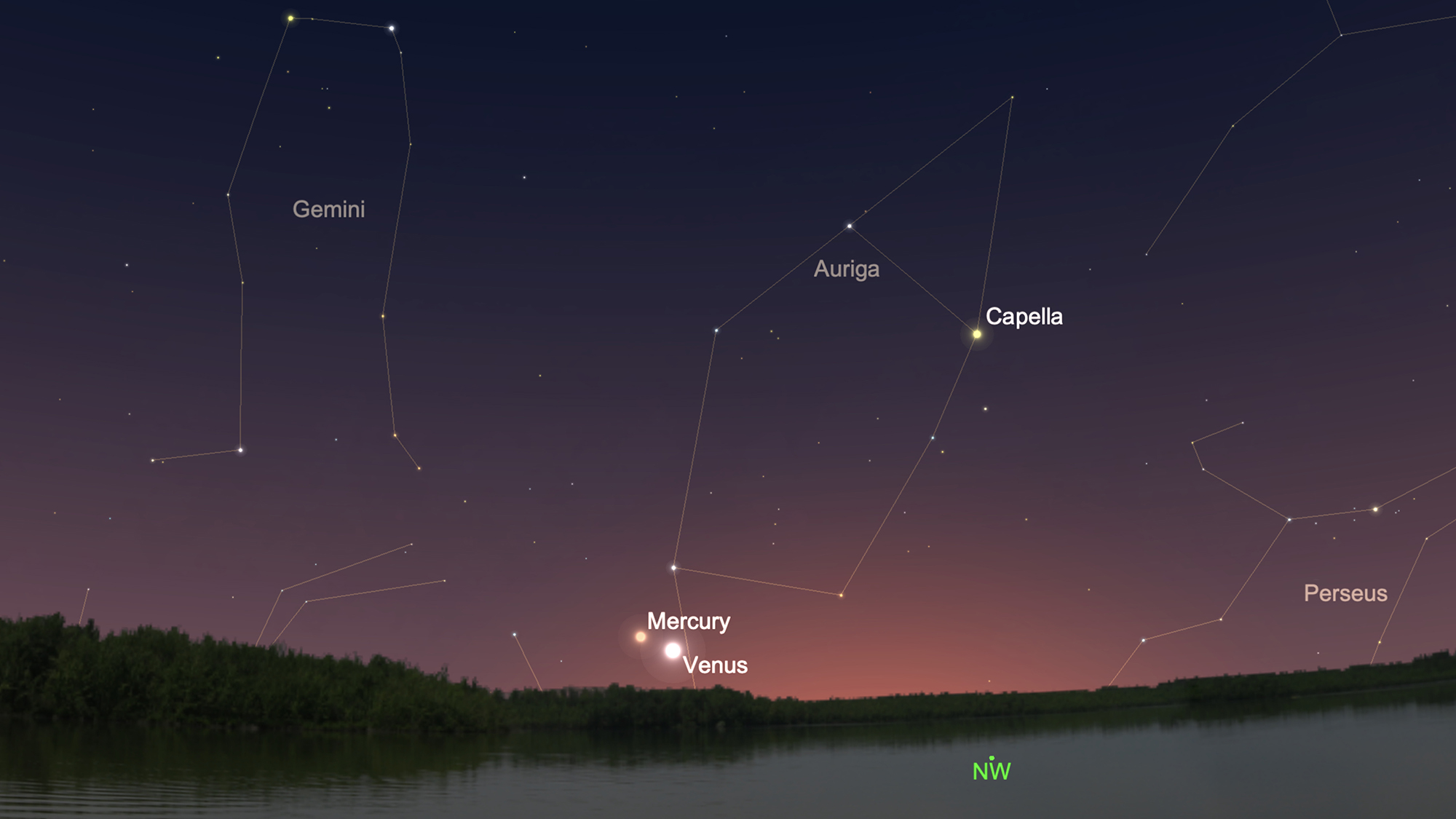

On May 4, Mercury was at superior conjunction and passed directly behind the disk of the sun from Earth's perspective, moving from west to east (or from right to left), after which it entered the evening sky. We now can see it, shining almost as brightly as Sirius, the brightest star in Earth's night sky, shining directly below Venus.

And come Thursday (May 21), the two planets will come closest together, like two ships passing in the night (or in this case, twilight). About 45 minutes after sunset, look low near the west-northwest horizon. Glaring Venus will of course, stand out against the twilight sky. Mercury will be 1.1 degrees below and slightly to the left. Although shining very bright in its own right, Mercury glows with only 4% the radiance of Venus. Binoculars will make sighting Mercury easy, although you should also be able to pick it out with your naked eye.

After Thursday night, the two planets will continue to go on their separate ways; Mercury continuing its steep climb upward, while Venus continues to rapidly fall downward. But one more event is still to occur. On Sunday (May 24), once again, concentrate low near the west-northwest horizon about 45 minutes after sunset. Venus will be there, albeit lower than it was just a few days ago. Mercury has now shifted 5.5 degrees to Venus's upper left. And 6.5 degrees to the upper left of Mercury you'll sight a slender waxing crescent moon.

Related: Moon phases

For sport, try sighting the moon on Saturday (May 23). It will be thinner and much lower, sitting to the lower left of Venus.

Ironically, as Venus bids a fond adieu to evening viewers at month's end, Mercury will be at its best, still shining bright at zero magnitude and setting nearly two hours after sundown, minutes from the end of evening twilight.

Same time and place (almost) every eight years

There is a highly noticeable rhythm in the motion of Venus: after eight years it returns to the same place in the sky on the same date. This was known and of great interest to ancient peoples such as the Mayans.

This happens because Venus goes around the sun an integral number of times — 13 — in eight years. The sidereal year of Venus — the amount of time it takes to complete one orbit around the sun — is 225 days (more precisely 224.7) and there are almost exactly 13 of these Venus-years in eight Earth years. The planet's synodic period, or the time it takes Venus to return to the same position in Earth's sky, is 584 days, and there are five of these in eight years. So, the behavior of Venus in 2012 repeats in 2020, 2013 repeats in 2021, and so on.

But actually I should insert a slight revision here. After eight years it returns almost to the same place in the sky on the same date. In actuality, it arrives almost to the same place two or three days shy of eight years. And when I say "almost to the same place," I'm talking about a relatively small difference measuring a little more than a few tenths of a degree.

Related: How to measure distances in the night sky

But such slight discrepancies are significant enough to deny us a view of an exceedingly rare celestial sight that occurred both in 2004 (on June 8) and 2012 (on June 5): A transit of Venus. Indeed, durings its last two eight-year cycles, Venus actually crossed in front of the sun and appeared in silhouette as a black dot about 3% the diameter of the sun's disk.

Such transits occur in pairs, each separated by eight years. But after the second transit, there comes a wait of over a century before the next takes place. The next time Venus crosses the sun will be on Dec. 11, 2117, though that will not be visible anywhere in the Western Hemisphere. But on Dec. 8, 2125, North America will be in an excellent position to watch as Venus again crosses the sun.

As for what happens this year, on June 3, at 1:36 p.m. EDT (1536 GMT), Venus will pass just 13.25 arc minutes or 0.22 degrees north of the sun's uppermost edge. Close ... but no cigar (or transit).

Rest of 2020: A morning wanderer

As for the rest of this year, Venus climbs less steeply out into morning twilight visibility, perhaps as early as June 6 (only 15 minutes before sunrise; use binoculars), though much better placed for making a sighting only a week later.

For the rest of the year it pulls away from us, passing about a degree north of the bright orange star Aldebaran during the second week of July, and soaring well up into the eastern predawn sky in August and September, though not quite so high as it did in March and April. Thereafter, it will spend the rest of the year sinking toward its passage behind the sun in March 2021.

Editor's note: If you have an amazing night sky photo you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, you can send images and comments to spacephotos@space.com.

- When, where and how to see the planets in the 2020 night sky

- Rare sight: Crescent Venus, Mercury spotted in daytime sky (photos)

- Venus and Mercury sparkle over Rome (photo)

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'All About Space' 'How it Works' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.