Here's every successful Venus mission humanity has ever launched

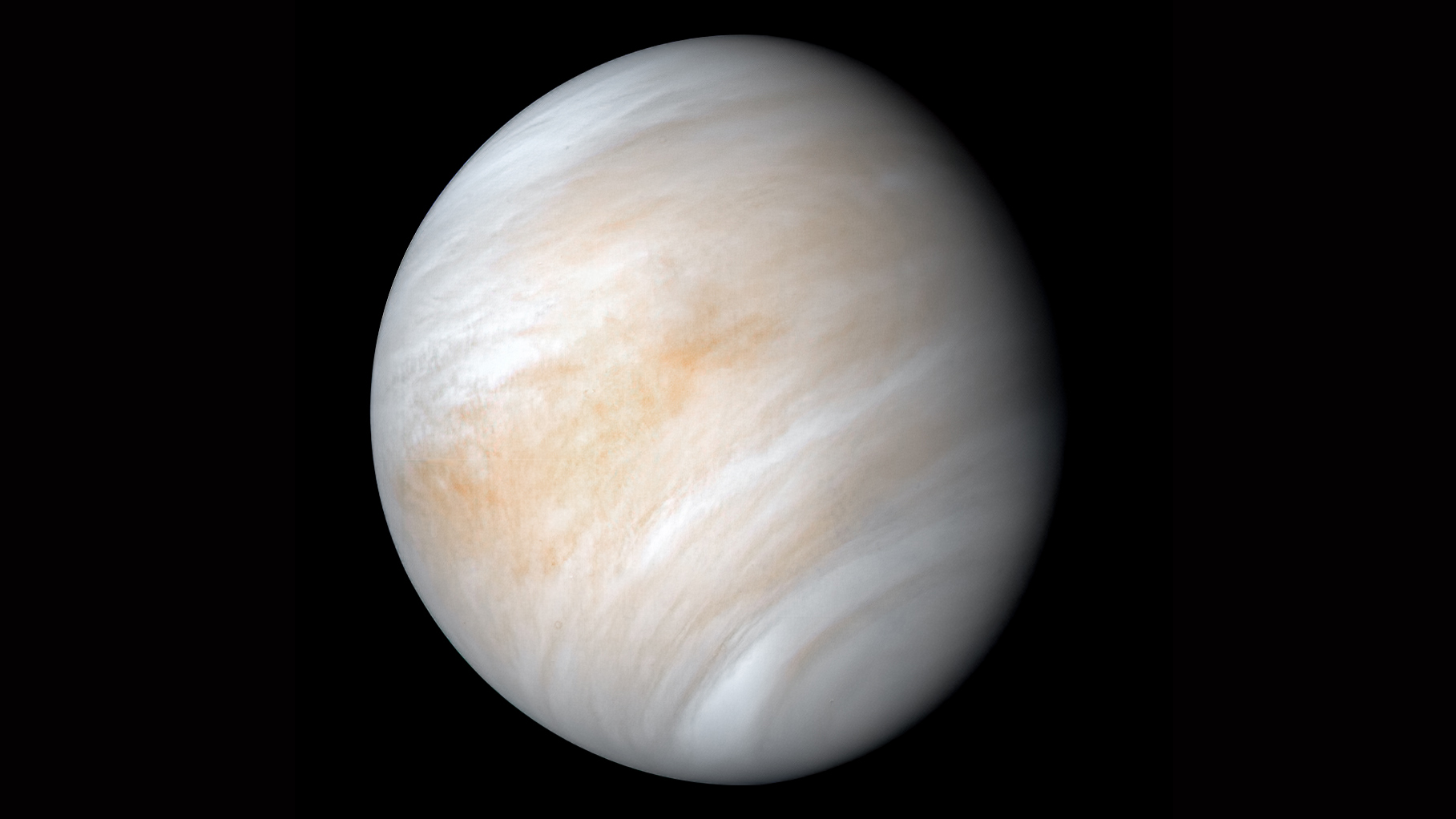

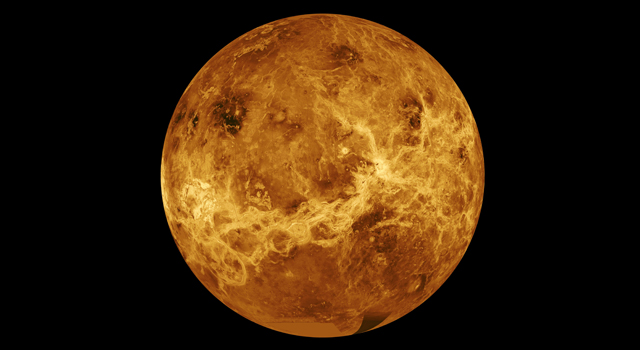

The planet Venus used to be thought of as a "twin planet" to Earth, with potential lush jungles lurking underneath the clouds. Telescopes and spacecraft instead revealed a hellish, volcanic environment with a dense atmosphere that can crush unprotected machines in moments. But we are learning much about Venus over the years.

This slideshow shows every successful Venus mission in history, according to NASA, skipping over those spacecraft that missed the target, lost communication before arriving or otherwise failed. Descriptions of each mission are drawn from the NASA website, with all dates given in GMT.

Related: The 10 weirdest facts About Venus

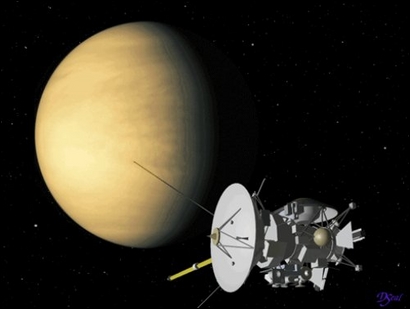

Mariner 2 — first successful Venus flyby (1962)

Mariner 2 was the first successful mission not only to Venus, but to any other planet. It made a flyby of Venus on Dec. 14, 1962. The NASA spacecraft recorded Venus' temperature for the first time, showing it has a surface temperature of roughly 900 degrees Fahrenheit (480 degrees Celsius). The spacecraft also detected the density, composition and variation of the solar wind, or the constant stream of charged particles flowing from the sun.

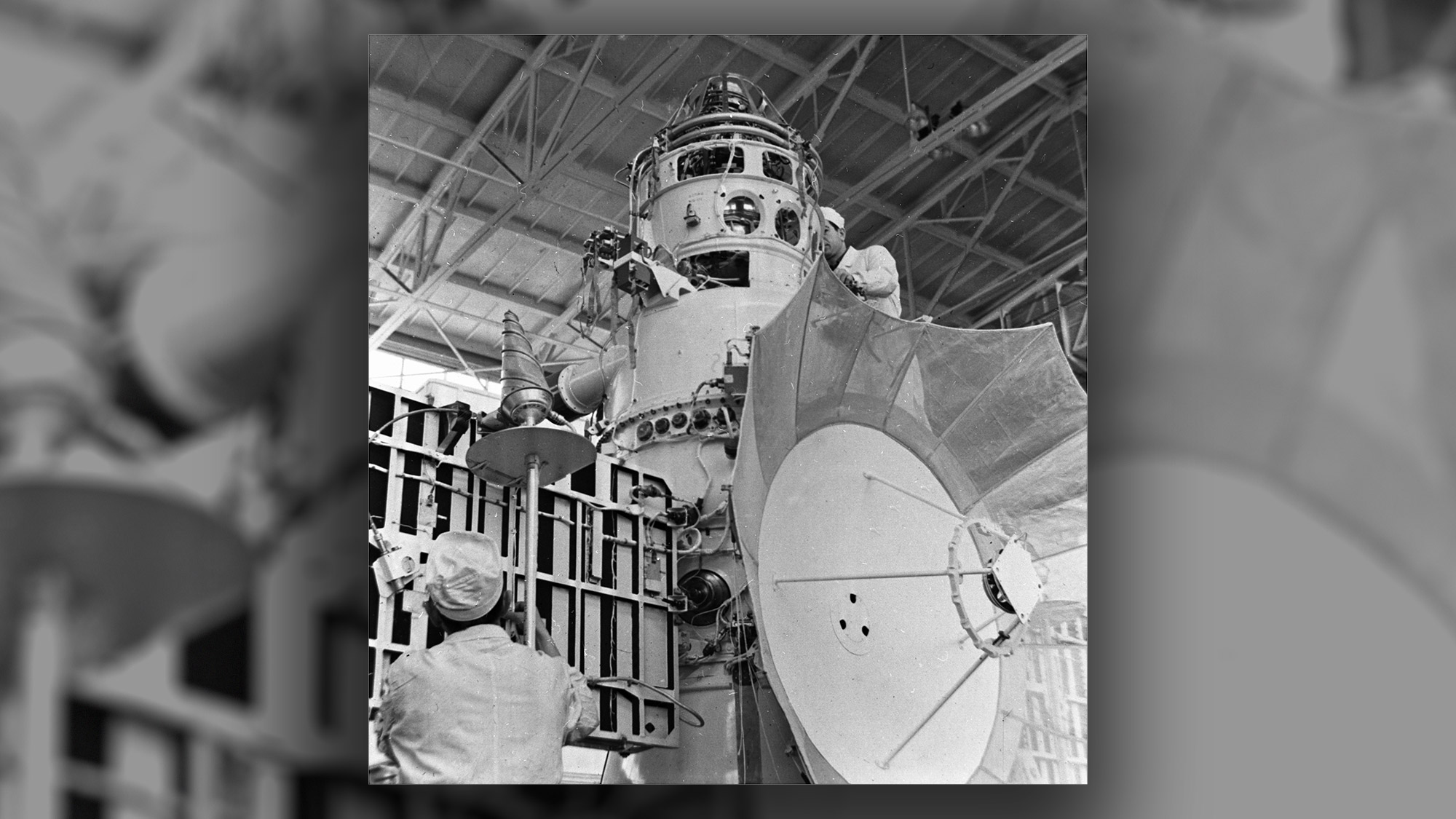

Venera 4 — atmosphere probe (1967)

Venera 4 was a Soviet Union spacecraft that was the first to successfully transmit information from the atmosphere of Venus. It entered the atmosphere on Oct. 18, 1967 and was not designed to make it all the way to the ground. The spacecraft showed an atmospheric composition of roughly 90% to 95% carbon dioxide, and found no evidence of a global magnetic field or radiation belts.

Mariner 5 — flyby (1967)

Mariner 5 was a NASA spacecraft that made its closest approach to Venus on Oct. 19, 1967. The spacecraft measured magnetic fields on Venus and in interplanetary space, and it examined charged particles, plasma (superheated gas), ultraviolet emissions and the amount by which radio waves are refracted in the atmosphere of Venus. This sort of information is helpful for scientists to understand the dynamics of a planetary atmosphere.

Veneras 5 and 6 — atmosphere probes (1969)

The Soviet Union's Venera 5 and 6 spacecraft were identical twin machines that each did successful flybys of Venus in 1969. Venera 5 entered the atmosphere on May 16, 1969 and sent readouts of the temperature, pressure and atmosphere for 45 minutes until it succumbed. Venera 6 also did a suicide plunge into the atmosphere on May 17, 1969, but its photometer failed to work. Taken together, the data from both spacecraft helped scientists better understand the composition of the atmosphere of Venus.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Venera 7 — first successful Venus landing (1970)

Venera 7 and a failed twin (Cosmos 359) both launched to Venus from the Soviet Union in August 1970. Venera 7 was the first spacecraft to successfully return data after landing on the surface of Venus. That said, the spacecraft had a rough landing on Dec. 15, 1970. The parachute ripped during descent and the probe hit Venus at a high speed (56 feet or 17 meters per second). The spacecraft sent a weak signal for roughly 23 minutes, although its transmissions only reached Earth briefly. It did manage to gather measurements from the atmosphere and the surface, despite its hard fall.

Venera 8 — Venus lander (1972)

The Soviet Union's Venera 8 and another failed twin spacecraft, Cosmos 482, both launched for Venus in 1972. Venera 8 landed safely on July 22, 1972 and managed to last 63 minutes on the surface before the high pressures and temperatures killed the transmission. The probe's mission confirmed that Venus has high surface temperature and pressure, and it also sent back data from the surface along with measurements of the regolith (soil) and clouds.

Mariner 10 — flyby of Venus en route to Mercury (1974)

Mariner 10 was the first spacecraft to use the gravity of one planet (Venus) to slingshot to a second planet (Mercury). It also was the first spacecraft to visit two planets. The NASA probe zoomed by Venus once on Feb. 5, 1974 and sent back the first close-up images of the planet from orbit. The spacecraft overcame several technical issues during its mission, including problems with a high-gain antenna and some attitude control issues.

Veneras 9 and 10 — Venus orbiters and landers (1975)

The Soviet Union's Veneras 9 and 10 each sent successful orbiters and landers to Venus. Venera 9 made a successful landing on Oct. 22, 1975 while Venera 10 alighted on the surface a day later. Both spacecraft transmitted TV photography from the surface and the mission as a whole recorded information about the planet's surface pressure, surface temperature, light levels and clouds, among other information.

Pioneer Venus Orbiter and Multiprobe — Venus orbiter and probes (1978)

This NASA mission is sometimes referred to as Pioneer Venus 1 and Pioneer Venus 2, and sometimes as Pioneer Venus Orbiter and Pioneer Venus Multiprobe. Whatever the naming convention, however, the orbital part of the mission successfully entered orbit at Venus on Dec. 4, 1978 and sent back information about the atmosphere and surface of Venus until 1992. The multiprobe part of the mission sent four probes into the atmosphere on Dec. 9, 1978. One probe even made it to the surface, which was more than anyone expected, and sent back information for more than an hour.

Veneras 11 and 12 — Venus flyby buses and landers (1978)

The Soviet Union's Venera 11 and 12 were twin spacecraft that flew to Venus in 1978. Each spacecraft included a flyby bus that would release a lander. Venera 12 touched down on the surface on Dec. 21, with Venera 11 following four days later. Each spacecraft survived for more than an hour after landing. As a whole, the mission gathered information about Venusian thunder, lightning and cloud components (like sulfur). Each spacecraft attempted to analyze the regolith (soil) on site, but did not succeed. The flyby buses also took scientific measurements from above Venus.

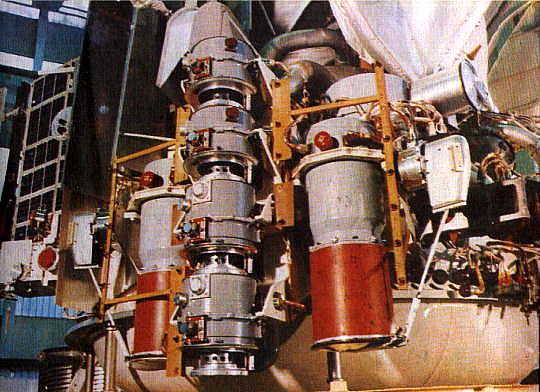

Veneras 13 and 14 — Venus flyby buses and landers (1981)

The Soviet Union sent another set of flyby buses and landers to Venus in 1981, called Venera 13 and Venera 14. Venera 13 landed on March 1, 1982, followed by Venera 14 four days later. The landers lasted between one hour and two hours on the surface, performing analyses of the soil, taking pictures and doing drilling. The flyby buses took scientific measurements from above.

Veneras 15 and 16 — Venus orbiters (1983)

The Soviet Union sent another pair of spacecraft to Venus in 1983: Venera 15 and Venera 16. This time, the mission focused on two orbiters that would take detailed images of the planet's surface. With two spacecraft available, this allowed for the ability to rapidly reimage a spot on the surface if needed. The spacecraft spent about eight months in orbit following arrival in October 1983 and transmitted data about the surface between the latitudes of the north pole and 30 degrees north.

Vegas 1 and 2 — Venus flybys, balloons and descent craft (1985)

The Soviet Union's next mission to Venus in 1985 combined two Venus flybys and later flybys of Halley's Comet, then in the inner solar system en route to its closest approach to Earth in 1986. Vega 1 did its flyby of Venus on June 11, 1985 and released a balloon and descent craft. Vega 2 successfully did the identical thing — a flyby, combined with releasing a balloon and a descent craft — four days later. All of these various mission pieces transmitted at least some data after flying by or arriving at Venus, providing a look at the planet from many different angles at the same time. The flyby spacecraft also imaged Halley's Comet successfully.

Magellan — long-lived Venus orbiter (1989)

NASA returned to Venus on Aug. 10, 1990 for its Magellan mission, which lasted for more than four years until radio contact was lost forever on Oct. 12, 1994. Magellan mapped the surface of Venus using synthetic aperture radar to better understand the topography of the planet. It managed to image many areas multiple times, with 98% of the surface mapped at resolutions better than 330 feet (100 meters). Data from the planet helped with scientific investigations into the planet's interior, and studying plate tectonics, impact craters and erosion on the surface.

Galileo — Venus flyby en route to Jupiter (1989)

NASA's Galileo spacecraft made one flyby of Venus on Feb. 9 and 10, 1990 as part of a series of planetary gravity assists to get to its ultimate destination, Jupiter, in 1995. Scientists used the brief opportunity to gather more data about the environment and atmosphere on Venus, although the main objective of the flyby was to get through it safely to bring the spacecraft to Jupiter.

Cassini — Venus flybys en route to Saturn (1998 and 1999)

The joint NASA-European Space Agency (ESA) mission Cassini-Huygens flew by Venus twice to pick up speed for the last destination of the mission, Saturn. (The spacecraft also went by Earth and Jupiter on the way there.) The Venus flybys took place on April 26, 1998 and June 24, 1999, and most of the science instruments were turned on to examine Venus and make practice observations for Saturn. Cassini arrived safely at Saturn in 2004 for many years of orbital observation of the planet and moons. It also released a small probe called Huygens that made a landing on Saturn's moon Titan.

MESSENGER — Two Venus flybys en route to Mercury (2004)

NASA's Mercury Surface, Space Environment, Geochemistry and Ranging (MESSENGER) mission made two flybys of Venus en route to Mercury, as part of a series of several planetary gravity assists. The Venus flybys took place on Oct. 24, 2006 and June 5, 2007, and the spacecraft took practice images and data of the Venusian surface and atmosphere before making it to Mercury's orbit in 2011.

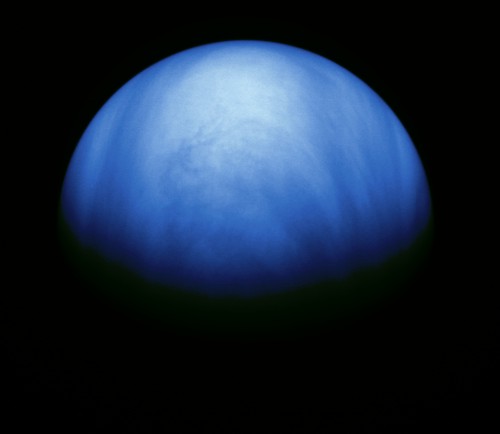

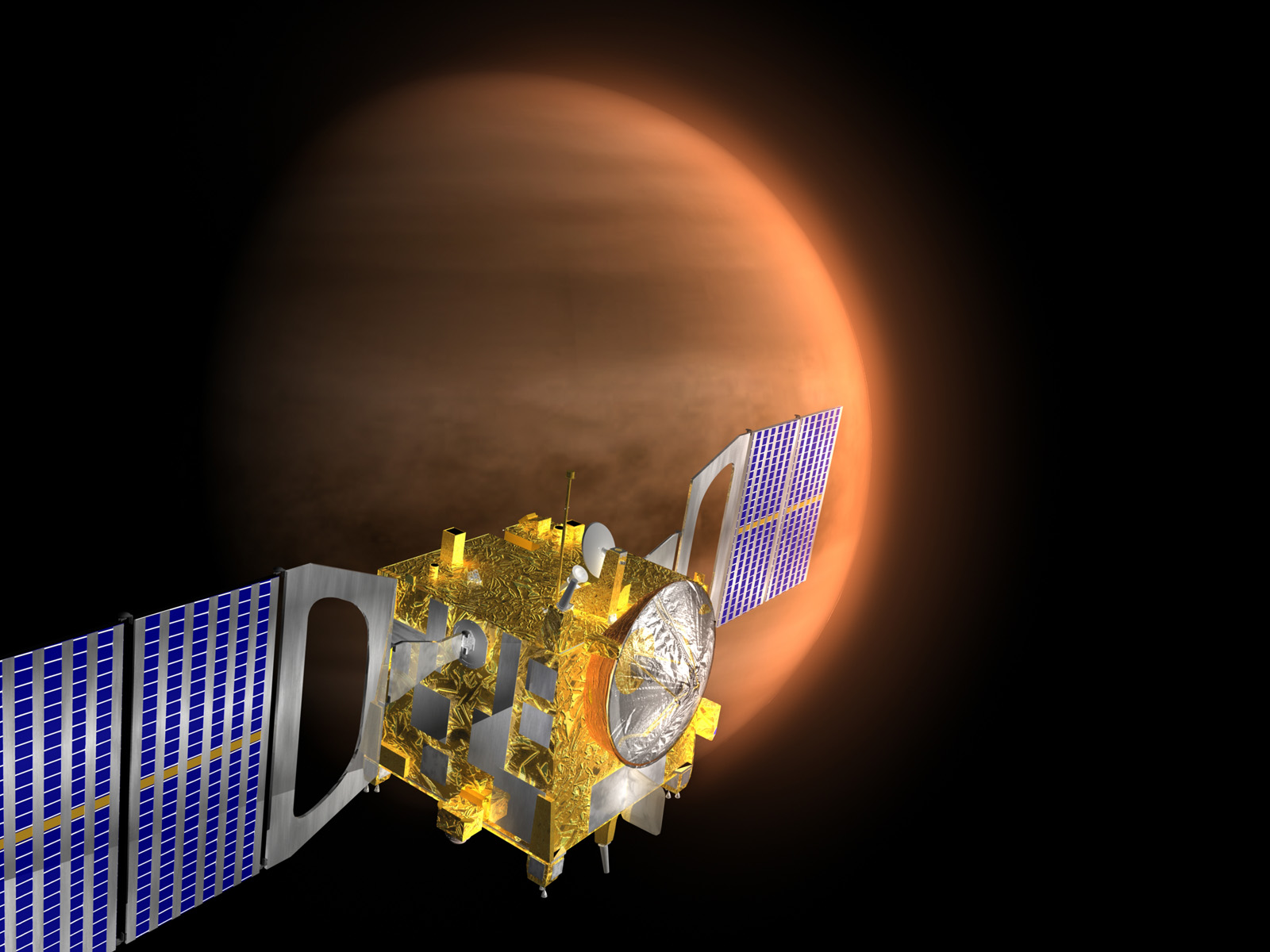

Venus Express — first European Venus orbiter (2005)

The European Space Agency's Venus Express was the first successful Venus orbiter mission successfully launched by any country besides the Soviet Union or the United States. The overall goal of the mission was to study the atmosphere and plasma of Venus from orbit starting in 2006, although the spacecraft made a series of planned dramatic descents closer to the planet before making a deliberate suicide plunge into the atmosphere in 2014. The mission had many investigations, some of which included looking at the greenhouse effect on Venus, how the atmosphere reacts to the solar wind, and properties of the Venusian magnetic field.

Related: Amazing Venus photos by ESA's Venus Express

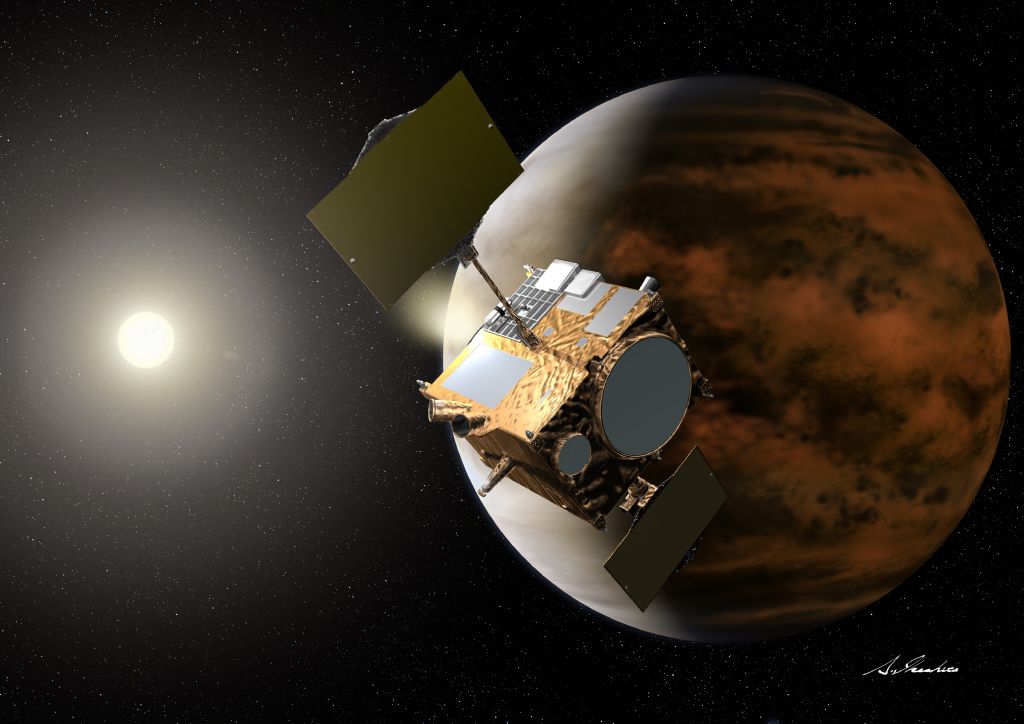

Akatsuki — first Japanese Venus orbiter (2010 attempt and 2015 success)

Akatsuki is the first Japanese orbiter at Venus. It attempted to enter orbit on Dec. 6, 2010, but a problem with the fuel pressure system caused the spacecraft to miss the mark. Luckily, Akatsuki remained in good health for five years and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) was able to make a second attempt on Dec. 7, 2015. This time, the spacecraft successfully entered orbit, and it has been transmitting data about the atmosphere and Venusian clouds ever since. Alternate names for the mission are the Venus Climate Orbiter and Planet-C.

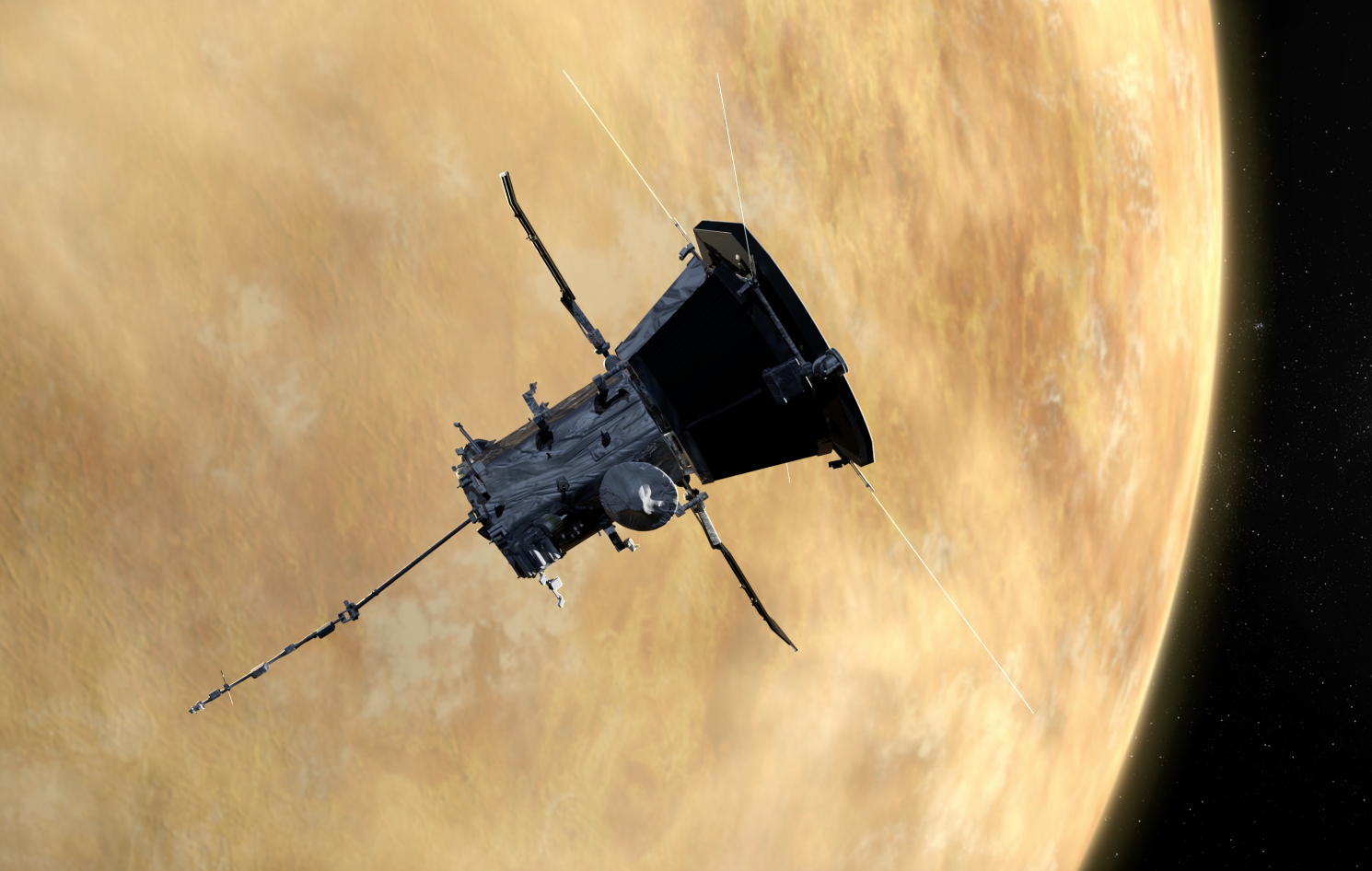

Parker Solar Probe and Solar Orbiter — multiple Venus flybys

Two currently operating solar spacecraft — NASA's Parker Solar Probe and ESA's Solar Orbiter — are making several flybys of Venus in the 2020s. Venus is being used to better position the spacecraft for solar flybys and to edge the spacecraft closely (yet safely) to our planet's nearest star. Parker Solar Probe launched in 2018 and Solar Orbiter in 2020.

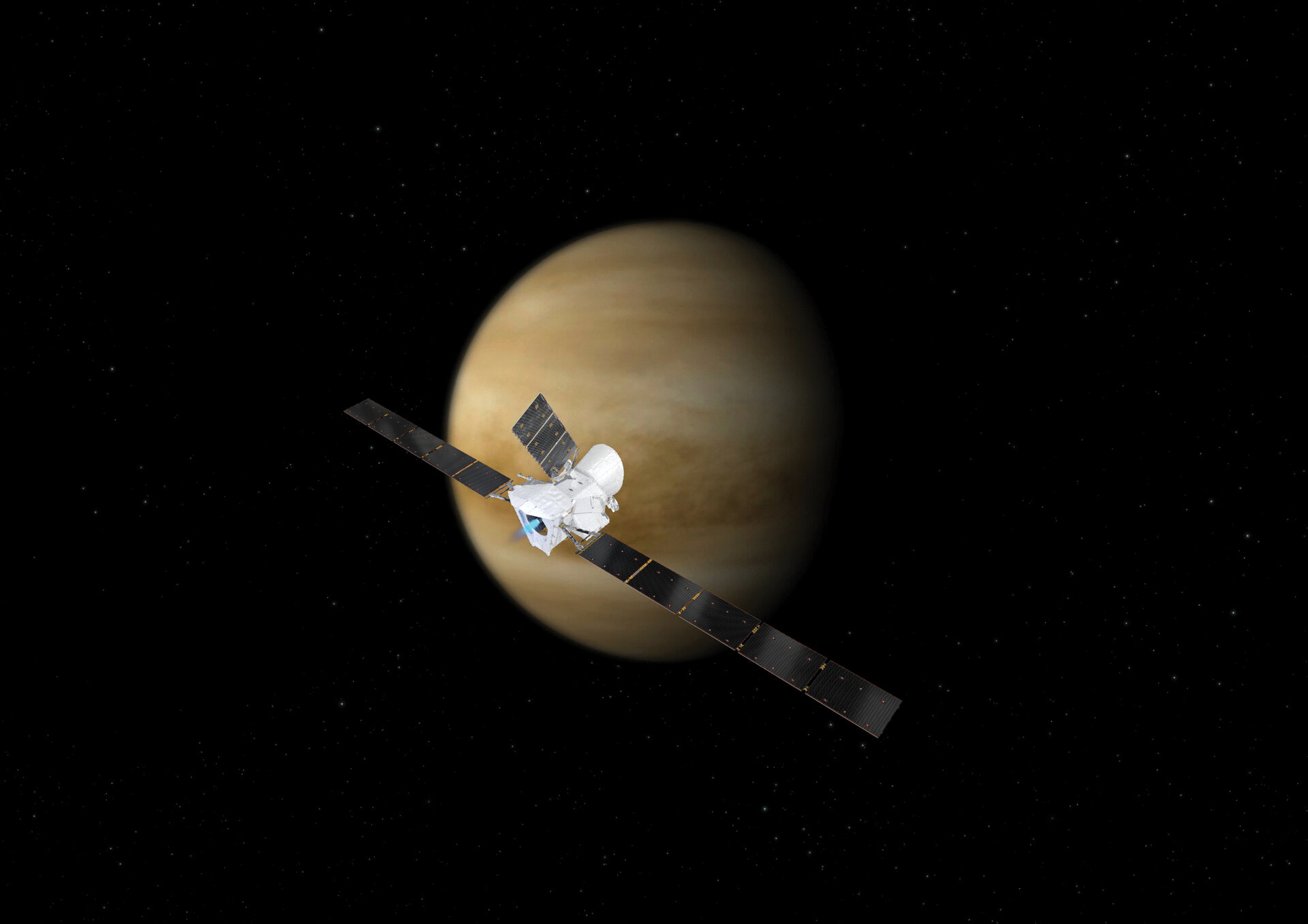

BepiColombo — 2 Venus flybys (2020 and 2021)

BepiColombo is a joint ESA and JAXA mission with two spacecraft that will arrive in Mercury's orbit in December 2025. Two flybys of Venus are planned on Oct. 15, 2020 and Aug. 11, 2021, and the spacecraft also has six planned flybys of Mercury to insert it into its final orbit. BepiColombo also flew by Earth on April 10, 2020.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.

-

Helio It's worth noting that only 1 in 13 missions were successful in the first 5 years of attempts (early '61 to late '65). But thereafter, it's 27 of 32 (88%).Reply