What is a 'morning star,' and what is an 'evening star'?

I once received an interesting inquiry from a woman who wanted to know the meaning of the terms "morning stars" and "evening stars." She wrote:

"I mean, they're not stars … they're planets, right? So why do we call them stars? And is a 'morning star' only visible in the morning, like at the crack of dawn, or at other times as well? Hope you can clear this up for me because I'm totally confused!"

Here is an explanation for what qualifies as a "morning star" and an "evening star."

Related: The brightest planets in the night sky: How to see them (and when)

It began with Venus

Originally, the terms "morning star" and "evening star" applied only to the brightest planet of all, Venus. It is far more dazzling than any of the actual stars in the sky and does not appear to twinkle. Instead, it glows with a steady, silvery light. The fact that Venus was a wandering star soon became obvious to ancient skywatchers, who noticed its shifting back and forth from the early hours of the eastern morning sky to the western sky in the early evening. Nicolas Camille Flammarion, a noted French astronomer in the late 19th and early 20th century, referred to Venus as "The Shepherd's Star." I myself like to refer to Venus as the "night light of the sky." So, one can readily understand the origin of the terms evening and "morning star" if we only considered Venus.

Of course, Venus is not the only wandering "star" in the sky; there are four others that are also visible to the unaided eye (five, if you include Uranus, which is barely perceptible without any optical aid on dark, clear nights). The difference is that, with the possible exception of Jupiter and, on rare occasions, Mars, none of the others stands out in the same manner as Venus. Nonetheless, somewhere in the distant past, "morning star" and "evening star" became plural in order to account for the four other planets.

When an evening star is branded as a morning star

It is quite understandable to see why the definitions of "morning star" and "evening star" can be confusing. Sometimes, for instance, we might see a bright planet like Jupiter shining brilliantly just above the eastern horizon in the evening. Within an hour or so, it has climbed well up into the eastern sky. "Ah!" you might say, "Jupiter certainly makes for a fine evening star." As the night wears on, Jupiter attains its highest point in the southern sky after midnight, and it will still be visible, sinking in the western sky at dawn. The giant planet is thus ideally situated for observations of its changing cloud bands and four big Galilean moons for much of the night.

The fact that Jupiter is already above the horizon during normal evening hours seemingly should qualify it for "evening star" status. But the distinction between these terms is not very precise, for yet, by the same reasoning, it is still considered strictly a "morning star."

How can that be?

Certainly, the "morning star" branding would make more sense if Jupiter were rising closer to, or even after midnight and crosses the southern meridian by sunrise. More on this in just a moment.

No double-meaning for the inner planets

With Mercury and Venus, however, there is never such ambiguity, since they are never very far from the sun in the sky. Because they orbit the sun more closely than Earth, Mercury and Venus are called "inferior" planets. In fact, in the pre-Christian era, both of these planets had dual identities — two names — as initially it was not realized they alternately appeared on one side of the sun and then the other. Mercury was called "Apollo" when it shone in the mornings and "Hermes" when it appeared in the evening sky; Venus was "Phosphorus" in the morning and "Hesperus" in the evening. We can thank Pythagoras around the 5th century B.C. for pointing out that the latter two objects were really one in the same.

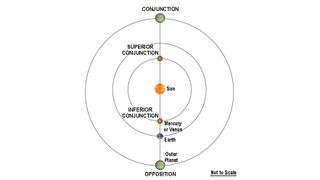

So, in general, when either of these planets has a western elongation from the sun it is a "morning star"; with an eastern elongation it is an "evening star." When they are aligned more-or-less with the sun as seen from our Earthly perspective, they will make the transition from evening to morning or vice versa:

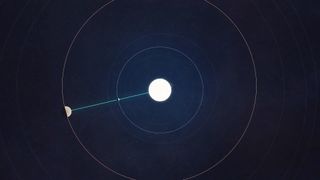

When Mercury or Venus is passing between the sun and Earth, we say they are at inferior conjunction and go from being categorized as "evening stars" to transitioning to "morning stars." When the alignment is such that they appear roughly on a line beyond the far side of the sun as seen from Earth, we then say that they are in superior conjunction; that is when they make the switch from being considered "morning stars" to "evening stars."

A celestial racetrack

An interesting analogy is to consider being a spectator at a motor speedway or racetrack and watching a race between two cars. If we consider for a moment that the two cars represent Mercury and Venus, and that the starting point was on that side of the track closest and directly in front of you (with an imaginary sun at the middle of the track), then that could also be considered as the point of inferior conjunction. As the two cars pull away from you and veer off to the right, they would simulate the changing positions of Mercury and Venus as "morning stars"; they would appear speed away to the right (west) of the sun in the sky, and as such would appear to rise before the sun.

Eventually, the cars would arrive at that point where they would appear to curve around and sweep back to the left. When they reached that point on the far side of the track, but were again directly in front of you, we would consider that to be superior conjunction. Now, the two cars are sweeping around to the left from our perspective, and simulating the changing positions of Mercury and Venus as "evening stars"; they would appear speed away to the left (east) of the sun in the sky, and as such would appear to set after the sun.

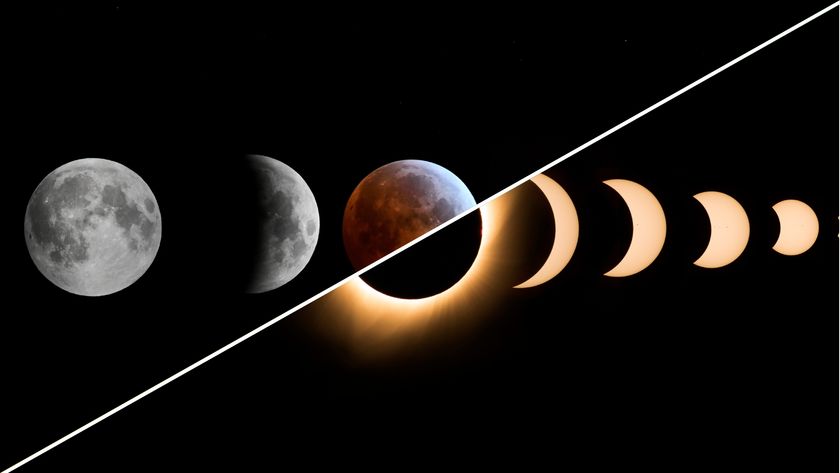

Transition at opposition

Things are somewhat different for the planets that orbit the sun beyond our own orbit — the so-called "superior" planets, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. In order to differentiate between what qualifies for the branding as a "morning star" versus an "evening star," we would say that during the time frame from when a planet is moving from its conjunction with the sun to just a day prior to its opposition (when it is directly opposite to the sun in the sky) it is considered a "morning star." At opposition, the superior planet in question would be rising when the sun sets and sets as the sun rises. From then on it is branded as an "evening star," rising or already in the sky as daytime ends.

Still, as we have already seen, the branding of a morning versus evening object might get a bit confusing, particularly in the few weeks leading up to opposition, when a superior planet is rising only an hour or two after sunset and is already well-placed for observation at a convenient evening hour and yet is still considered a "morning" star. This is particularly true during the wintertime when the sun sets rather early in the evening. If a planet like Mars, does not emerge above the eastern horizon until an hour or two after sunset, it will still be branded as a "morning star" even though it is shining brightly for all to see during convenient prime-time evening hours!

A change in venue

Incidentally, if we try to use our race track analogy in the case of the superior planets, we'd have to make an important change, because unlike the inferior/inner planets, which are racing around the sun more rapidly than Earth, our home planet in contrast, is moving more rapidly around the sun compared to the superior/outer planets.

So rather than being a spectator at the race, we would need to become a participant!

On the race track, our car would always be chasing, overtaking and ultimately leaving the slower cars that are representing the superior planets behind. They would all be positioned on the outside of the track, to our right. And because of this perspective, when a superior planet is on the far side of the track as seen by us (and becomes aligned with the sun), the more rapid motion of our Earth causes the slower planet to appear to drop back toward the sun in our evening sky until it arrives at solar conjunction. Then several weeks later it emerges back into view in the morning sky, rising before sunrise.

Interestingly, when they are passing behind the sun, the inferior planets appear to move from right to left, transitioning from the morning to the evening sky. But for the superior planets, it is just the opposite: They appear to move from left to right when making the transition from the evening into the morning sky.

Additional reading and resources

There are scores of excellent books and publications about the planets. For those who want to study the subject further, here is a short list of some of them:

"A Field Guide to the Stars and Planets," 4th ed., by Donald H. Mensel and Jay M. Pasachoff (Houghton Mifflin, 1999)

"Observer's Handbook" (Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, Annual Publication)

"Skywatching" by David H. Levy (The Nature Company Guides/Time-Life Books, 1995)

"Stars" by Herbert S. Zim and Robert H. Baker (Western Publishing Co., Inc 1975)

"Stars & Planets" by Ian Ridpath and Wil Tirion (Princeton University Press, 2008)

"The Planets" by Nirmala Nataraj and Bill Nye (Chronicle Books, 2017)

"The Planets: The Definitive Visual Guide to our Solar System" by Robert Dinwiddie and 7 others (Dorling Kindersley Limited/DK, 2014)

Bibliography

- "Popular astronomy – A General Description of the Heavens" by Camille Flammarion, translated from the French with the author's sanction by J. Ellard Gore (New York D. Appleton and Company 1894). Page 331.

- "How Did Mercury Get Its Name?" Universe Today. https://www.universetoday.com/66432/how-did-mercury-get-its-name/

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.