Venus views from NASA sun probe show potential of hitchhiking science instruments

Halfway through a series of opportunistic Venus observations, scientists say that a NASA sun spacecraft's success studying our strange neighbor will pave the way for future measurements.

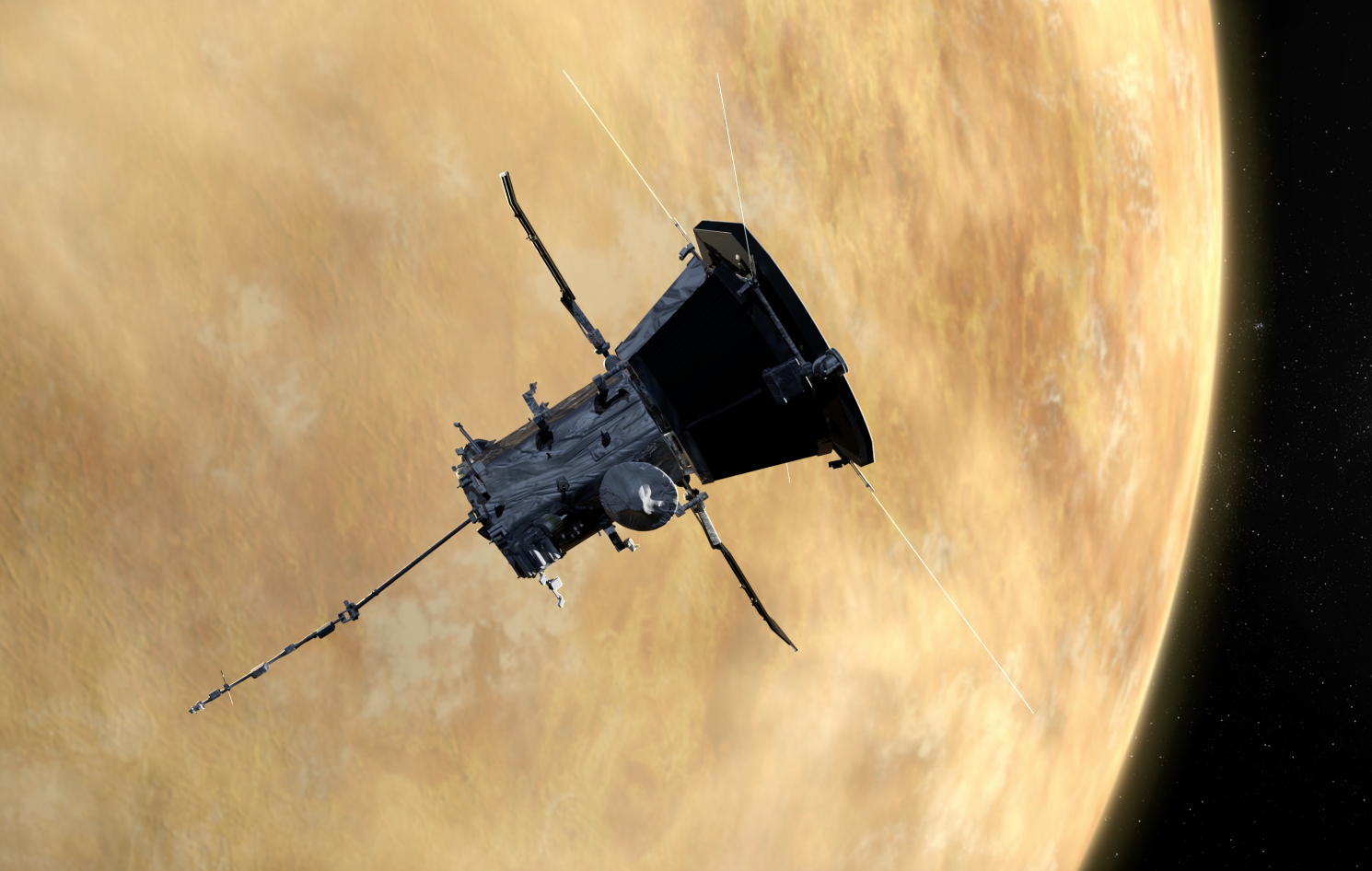

NASA's Parker Solar Probe launched in August 2018 on a seven-year mission to touch the sun, dancing through our star's corona, the sun's superhot atmosphere that is invisible but shapes conditions across the solar system. That mission requires a trajectory creeping closer to the sun's visible surface with each flyby, achieved by a series of seven swings past Venus. So, before Parker Solar Probe launched, atmospheric scientists made a case for why the spacecraft's scientific instruments should be turned on during Venus flybys. Now, after just four of those Venusian maneuvers, the project's success may point to a new way of studying Venus.

"I've just been really, really impressed with how excited people are for any observations at Venus," Shannon Curry, a planetary physicist at the University of California, Berkeley, told Space.com.

Related: NASA's Parker Solar Probe captures stunning Venus photo during close flyby

Venus hosts just one full-time robotic explorer these days, Japan's Akatsuki mission, and the planet has received surprisingly few recent spacecraft visitors, considering the world is just next door to Earth. So scientists jumped at this opportunity for new observations.

Because Parker Solar Probe is optimized to study the sun, not a planet, the project's success in gathering this extra Venus data can show the feasibility of using clever mission operations techniques to turn trajectory maneuvers into science opportunities. The U.S.-European Solar Orbiter spacecraft and the European-Japanese BepiColombo mission to Mercury also require Venus flybys to steer to their destinations, and Curry said she and colleagues are working with both mission teams to guide potential observations based on how similar instruments aboard Parker Solar Probe have performed.

"We give each other a heads up on like, 'Here's what to look for, here's how you can get the best science,'" Curry said. "All of us have sort of gotten on the bandwagon of let's make these flybys count."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

However, because the instruments that scientists are "borrowing" to observe Venus are fairly small, similar equipment could also find a home on full-fledged Venus missions to round out scientists' understanding of the phenomena that Parker Solar Probe and others can study only briefly.

"A lot of these particle and fields instruments are pretty light," Curry said. "These are sort of shameless advertisements for saying, like, 'Hey, it's not that hard to add this.'"

NASA isn't committed to any Venus-specific spacecraft right now, but there are a host of potential missions to the planet under serious discussion, including two projects NASA may select later this spring and mission concepts that Europe, India and the U.S. company Rocket Lab are considering. Scientists have also evaluated what they could learn with a Venus mission at the scale of NASA's so-called "flagship missions," like its Mars rovers.

Dedicated Venus spacecraft tend to focus on questions about the planet's surface and thick atmosphere, rather than untangling how the planet's atmosphere interacts with its surroundings and with the sun, as Parker Solar Probe is doing.

But the distinction between studying Venus and studying its relationship with the surrounding environment isn't as clear as all that. For example, if scientists want to learn about, say, how the Venusian atmosphere and its potential habitability may have changed over the planet's history, it's helpful to know what ingredients in its modern atmosphere are slipping into interplanetary space, and how quickly.

And that's the sort of observation that Parker Solar Probe has aced, Curry said.

Exploration at a tiny scale

In particular, she's been pleased with the data the probe has gathered about what types of charged particles are traveling in the transition zone between the Venusian atmosphere and interplanetary space and how quickly those particles are moving. Previous missions, like NASA's Pioneer Venus Orbiter and the European Space Agency's Venus Express, have studied these charged particles, but could only estimate their identity and speed. Instead, Parker can identify particular flavors of ions and clock their movements.

"We have a much, much better picture," Curry said of the new Parker Solar Probe observations compared with data from much older, dedicated Venus missions. "It's like those photos in the 1900s where things are a little blurry and everybody's sort of sitting very, very still. And now we actually have sort of like the live iPhone photos."

Parker Solar Probe's observations have also revealed a host of tiny, short-lived phenomena in Venus' electric and magnetic fields. "These are really, really, really tiny things," Curry said of these detections. "But we finally effectively have like a microscope there that we can start to understand these sorts of things with, and we've never had anything close to that."

Moreover, some of these observations are the first detections of such phenomena at a world besides Earth. Curry said such detections should help scientists begin to understand what is unique to our world and what may, in fact, be common across the solar system.

So far, Parker Solar Probe is painting a picture of magnetic and electric fields, charged particles from the sun and from the planet, and other phenomena interacting in a way that's very different from what scientists had expected, which was a straightforward teardrop-shaped bubble.

"We now know that it's a significantly more complex and complicated interaction," Curry said, "in a really good way, like in a fun, complicated way."

Meanwhile, Parker Solar Probe still has three more Venus flybys of its own to execute: one in October, then a pair in 2023 and 2024. The last flyby, in November 2024, will occur near the end of Parker Solar Probe's mission and near the peak of the solar cycle, and it will pull the spacecraft into the bubble-like bow-shock surrounding Venus, just as the two most recent flybys did.

"[Flyby number] seven's just going to be a beast," Curry said. "I'm super excited for it."

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.