Of the five bright naked-eye planets, by far the easiest and brightest to see is Venus. There never seems to be a problem in locating this dazzling world, whether it is in the morning or evening sky. Still, there are occasions when Venus is not very well placed for viewing.

And 2021 is going to be one of those times.

First, you might have been wondering where the most brilliant of all the planets has been in recent months. It has been visible neither in the morning sky before sunup nor in the evening sky after sundown. In fact, Venus has been on a sort of late winter and early spring sabbatical — too close to the glare of the sun — to be seen.

Related: The brightest planets in May's night sky: How to see them

Venus passed superior conjunction (appearing to go behind the sun as seen from Earth) on March 26. Since then, it has been invisible, mired deep in the brilliant glare of the sun. Nonetheless, ever since then, it has been moving on a slow course toward the east and pulling slowly away from the sun's general vicinity.

Some assiduous observers were able to catch a brief glimpse of Venus on April 24, about 20 minutes after sunset when it passed within about a degree of the planet Mercury. Finally, in the coming nights, it will begin to emerge as an evening "star" for all to see, albeit very low in the western twilight.

This week the planet sets in the west-northwest about an hour after sunset. By Memorial Day (May 31) this will have improved to 80 minutes, giving most observers a chance for their first view of the famed "evening star." It's so bright that it can be spotted even through twilight very low in the west-northwest 45 minutes after sunset, so look early, preferably with binoculars.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

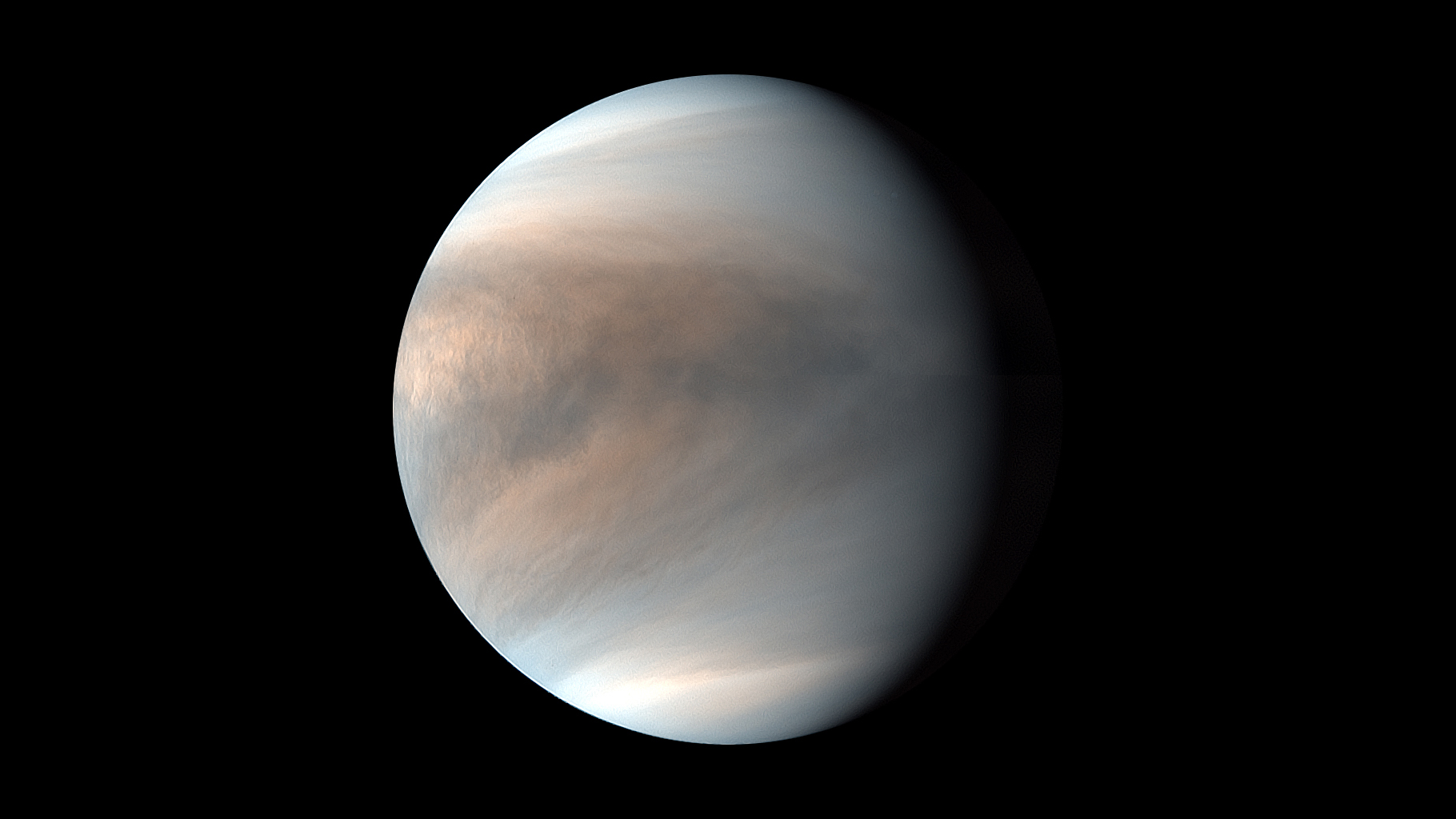

Appearing as a brilliant white star-like object, our sister planet will adorn the western evening sky through the remainder of this year.

An arresting, but difficult sight

Each month through December, Venus will engage the moon in a conjunction, meaning the two objects will appear close together in the sky. But the conjunction where the two will appear closest will be the one that will occur on Wednesday, May 12. You will need a flat and unobstructed view of the west-northwest horizon as both the moon and Venus will appear very low shortly after sunset. Your best chance will come a half-hour after sunset, when they will appear only 5 degrees above the horizon. Your clenched fist measures roughly 10 degrees in width when held at arm's length, so both moon and Venus will appear only about a "half fist" up.

Binoculars will be very beneficial in making a sighting against the twilight sky; Venus will probably be easier to see because it will be a bright, sharp point of light glowing a little over one degree to the right of an exceedingly thin, hairline crescent (only 1% sunlit). Both will set only an hour after the sun. Incidentally, if you're on Easter Island, eastern Polynesia and most of New Zealand, the moon will appear to occult (hide) Venus.

A second-rate apparition

Unfortunately, for most of us north of the equator, this is going to turn out to be a rather sub-par evening apparition of Venus, especially during the upcoming summer months. The reason for this is that from now right on through late summer Venus is going to always remain unusually low in the western twilight sky right after sunset.

From the end of May on through the beginning of September, Venus will never appear higher than "one fist" up from the horizon at mid-twilight (roughly an hour after sunset). And in fact, at no time through all of July, August and on into the second week of September, will Venus be visible against a completely dark sky, as it will set no more than about 90 minutes after sunset; before the end of evening twilight.

Expect better things by autumn

But beginning with the second week of September, our view of Venus will begin to slowly improve. For one thing, Venus will be getting noticeably brighter as it rounds the sun and speeds closer to Earth.

Also, its angular distance from the sun in the sky will be increasing, meaning it slowly will start setting later: on Sept. 7, 1 hour and 33 minutes after the sun; Oct. 1, 1 hour and 45 minutes; Nov. 1, 2 hours and 22 minutes and by Dec. 1, 2 hours and 46 minutes after the sun. And because twilight fades much faster in the fall than in the summer, Venus will shine in a darker sky; beginning Sept. 12, Venus finally sets just after the sky has become completely dark.

Venus reaches its greatest elongation — its greatest angular distance — 47.1 degrees to the east of the sun on Oct. 29. It reaches its pinnacle of brilliance for this apparition on Dec. 3 at a lantern-like magnitude of -4.9. By then it will be an eye-catching sight in the southwest sky for at least a couple of hours after sunset — serving as an evening "Christmas Star" right on through most of the winter holiday season.

That will also be when I likely will be getting inquiries about what that "large, bright star" in the southwest after sunset, as now even a casual glance will reveal it. Many will be surprised when I tell them that Venus has been out there since mid-spring and will insist that isn't true and that they've only just now noticed it; an artifact of it spending much of 2021 hovering low and mired in bright twilight.

Large, slender crescent

After Christmas Venus will quickly fade, vanishing from view soon after the turn of the new year, and passing inferior conjunction on Jan. 9. By mid-January it will reemerge as the "morning star" low in the southeast sky.

Between now and year's end, if you track Venus with a small telescope, you'll be able to follow its complete range of phases and disk sizes. At the moment, Venus is virtually full (98% sunlit), and appears as nothing more than a tiny, dazzling disk. It will become noticeably less gibbous by late summer. Then, come the end of October, Venus reaches dichotomy (displaying a "half moon" shape). For the rest of the year, it displays an increasingly thinning crescent as it swings near the Earth. By Dec. 2, its large crescent shape should be easily discernible even in steadily held 7-power binoculars.

And by Dec. 29, this crescent will have thinned to just 4% illuminated but will attain a width of about 3% the apparent diameter of the moon. If you have particularly acute vision, it just might be possible for you to perceive this large/thin crescent without any optical aid.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.