Many people I'm sure have referenced an idiom by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, "Ships that pass in the night." Well, come early Monday morning (Feb.18), you'll be able to watch two planets that will pass in the dawn. One planet is very slowly descending into the dawn twilight and into eventual obscurity, while the other will become increasingly prominent in the weeks and months to come.

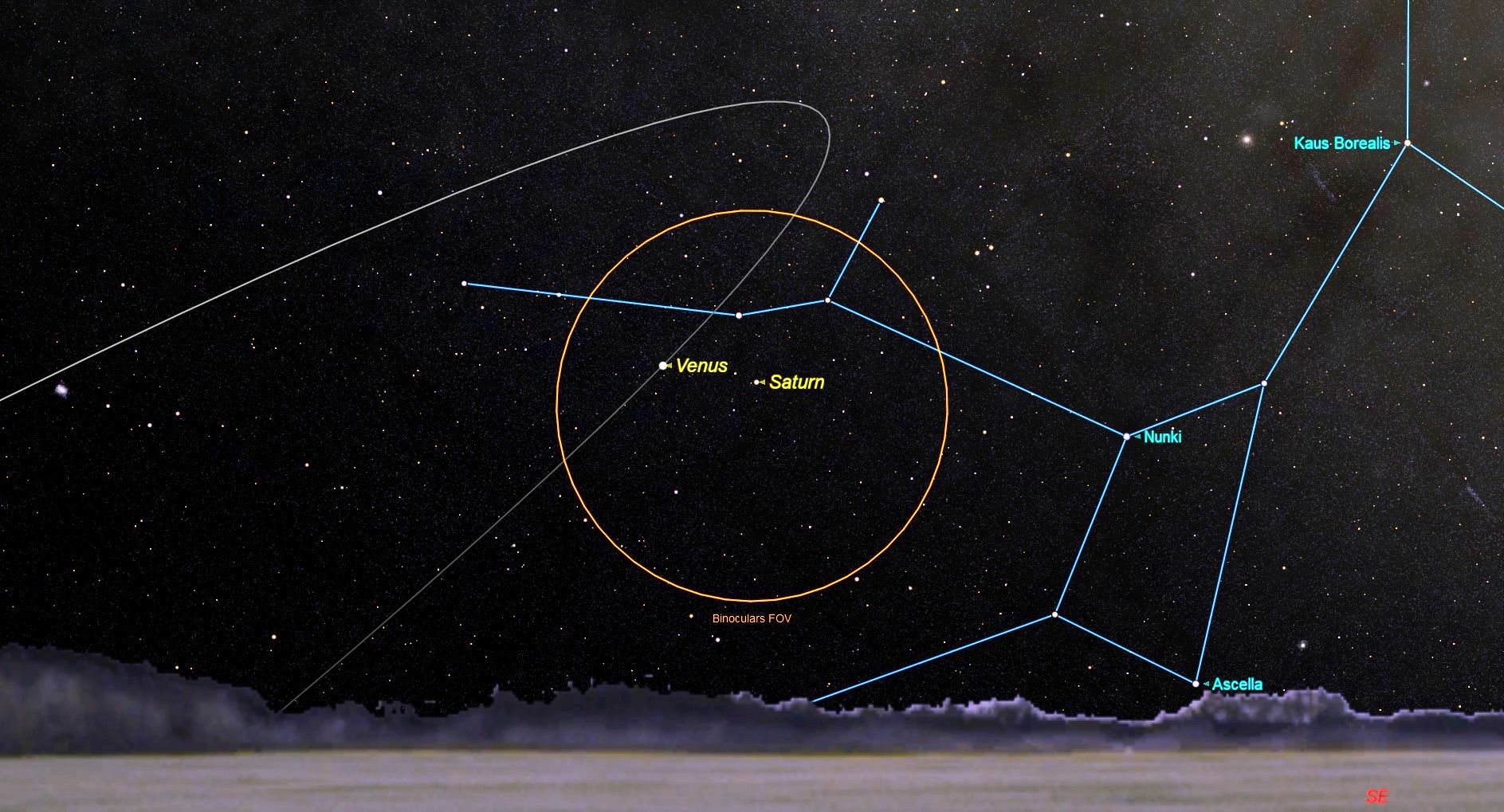

The planets in question are Venus and Saturn. Look for them around 5:45 a.m. local time, low above the southeast horizon. Brilliant Venus, shining with a steady silvery-white glow, will be passing about 1.1 degree above and to the left of the much dimmer and yellower Saturn. If you have a telescope you might want to try to get a view of its breathtakingly beautiful rings, although its low altitude — just 10 degrees above the horizon — will be a bit of a handicap since atmospheric turbulence can make for a rather unstable image.

The tilt of the rings was at a maximum in October 2017, but they are still "wide-open" from our earthly perspective, some 24.5 degrees from edgewise. As for Venus, it displays a rather small gibbous shaped disk, 69 percent illuminated by the sun. Venus outshines Saturn's larger but duller disk and rings by some 70-fold. [Winter Skywatching: Spot Some Overlooked Constellations]

One dazzles, the other is sedate

If you look at both Venus and Saturn through a telescope, Venus is unquestionably the brighter of the two objects. But you might wonder how this is possible. After all, both planets are perpetually covered with clouds and their respective albedos — the proportion of the incident sunlight reflected by those clouds — are exactly the same at 76 percent. Why, then, does Saturn appear so much duller than Venus if both are reflecting the same proportion of sunlight back toward Earth?

The key is their distances from the sun.

Venus is currently 92.6 million miles (149 million kilometers) from Earth. Saturn is 1 billion miles (1.6 billion km) away. So compared with Venus, Saturn is 10.8 times farther away from the sun. And if we use the inverse square law — which states that the intensity of reflected sunlight is inversely proportional to the square of the distance from the sun — then 10.8 multiplied by 10.8 shows that sunlight striking Saturn's cloud tops is 116.7 times weaker compared with sunlight striking the cloud tops of Venus.

Later this year, both planets will cross paths with each other again — this time in the evening sky — on Dec. 11.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In any case, arise early on Monday and take a peek as the Goddess of Beauty snuggles up to the God of Time.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for Verizon FiOS1 News in New York's Lower Hudson Valley. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.