There is no question which is the most prominent planet this month. It's certainly none other than dazzling Venus, which rules the western evening sky this month, offering spectacular views as it reaches its greatest brightness of the year.

Over a 30-day time span, the bright "evening star" will:

- Skim the Pleiades star cluster

- Shine at its brightest

- Present a long and narrowing crescent in telescopes

- Stay up well past its normal viewing time after sunset, and

- Team up with a lovely crescent moon.

Let's go point by point through our list.

Related: Photos of Venus, the mysterious planet next door

Venus "kisses" the Seven Sisters

Venus will appear dramatically close to the Pleiades during the first several evenings of April. On April 1, we can see it hovering just below this beautiful open cluster of stars, known colloquially, as "The Seven Sisters."

On the evening of April 3, Venus is just one-quarter of a degree southeast of Alcyone, the brightest star in the cluster, and one-third of a degree south of the neighboring stars Atlas and Pleione. Venus is only about three-quarters of a degree from the cluster's center on the night before and a little over 1 degree the night after.

Venus's glare will practically overwhelm the cluster for naked-eye observers when it is closest, but binoculars and wide-field telescopes will show both the planet and the cluster beautifully. Only once every 8 years can Venus come so near the Pleiades — and in our lifetime these conjunctions (or close encounters) have been getting ever closer. As Venus continues to pass a little farther north, it will actually go right through the main Pleiades stars in the years 2028, 2036, 2044 and 2052.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The pinnacle of brilliance

Venus starts April at magnitude -4.5 (magnitude is a measurement of brightness used by astronomers, with lower numbers denoting brighter objects. Negative numbers denote exceptionally bright objects.) On April 27, the planet reaches a magnitude of -4.7, the brightest it will become this year, also referred to as its "greatest illuminated extent." — a compromise between its increasing apparent size and the diminishing illuminated portion of its disk.

On this date Venus will appear to shine more than nine times brighter than its nearest planetary competitor (Jupiter) and will outshine Sirius, the brightest of all stars, by more than 20-fold. In dark locations free of significant light pollution, the planet's light is bright enough to cast faint but distinct shadows. And if you know precisely where it is, you'll be able to see it in the daytime: a tiny white speck against the blue background sky.

An increasingly large, narrowing crescent

Telescopes will show Venus's apparent diameter noticeably increasing in April while its phase thins from 47% to 25% lit. If you hope to see any subtle detail in Venus's clouds, observe before the sky gets too dark and Venus dazzles with glare.

As we have just alluded to, this is an ideal month to view the crescent of Venus in broad daylight through binoculars, a telescope — or even (if you have exceptional vision) with your naked eyes.

Related: Examining the phases of Venus

Staying up late

In not a few astronomy guidebooks, you'll read that Venus always remains close to the sun's vicinity, setting within a few hours of the sun and is never visible at midnight. But this month, for viewers living in mid-northern latitudes from April 7 through April 22, Venus will be setting unusually late; after 11:30 p.m. local time.

However, it should be noted that we provide local mean time (LMT) of rise and set times, not their civil time. Our civil time zones are standardized on particular longitudes. Examples in North America are Eastern, 75 degrees west; Central, 90 degrees; Mountain, 105 degrees; Pacific, 120 degrees. If your longitude is very close to one of these (as is true for Philadelphia, New Orleans and Denver), luck is with you and this correction is zero. Otherwise, to get standard time you'll need to add 4 minutes for each degree of longitude that you are west of your time zone meridian, or subtract 4 minutes for each degree you are east.

Thus, for a place like Boston, which is about 4 degrees east of the Eastern standard meridian, you'll need to subtract 16 minutes. So Venus will actually set before 11:30 p.m. during that April 7-22 time frame. On the other hand, Indianapolis, is 11 degrees west of the Eastern standard meridian, so you'll need to add 44 minutes. So in reality, as seen from the city nicknamed the "Crossroads of America," Venus will appear to set after midnight; as late as 12:18 a.m. on April 15!

Of course, another factor is that much of the country (save for Arizona and Hawaii) is also currently on daylight saving time. And that is the primary reason why the "goddess of love" stays up unusually late this month. If, for example, we were still observing standard time, then from Indianapolis Venus would set at 11:18 p.m. on April 14.

A final evening celestial tableau

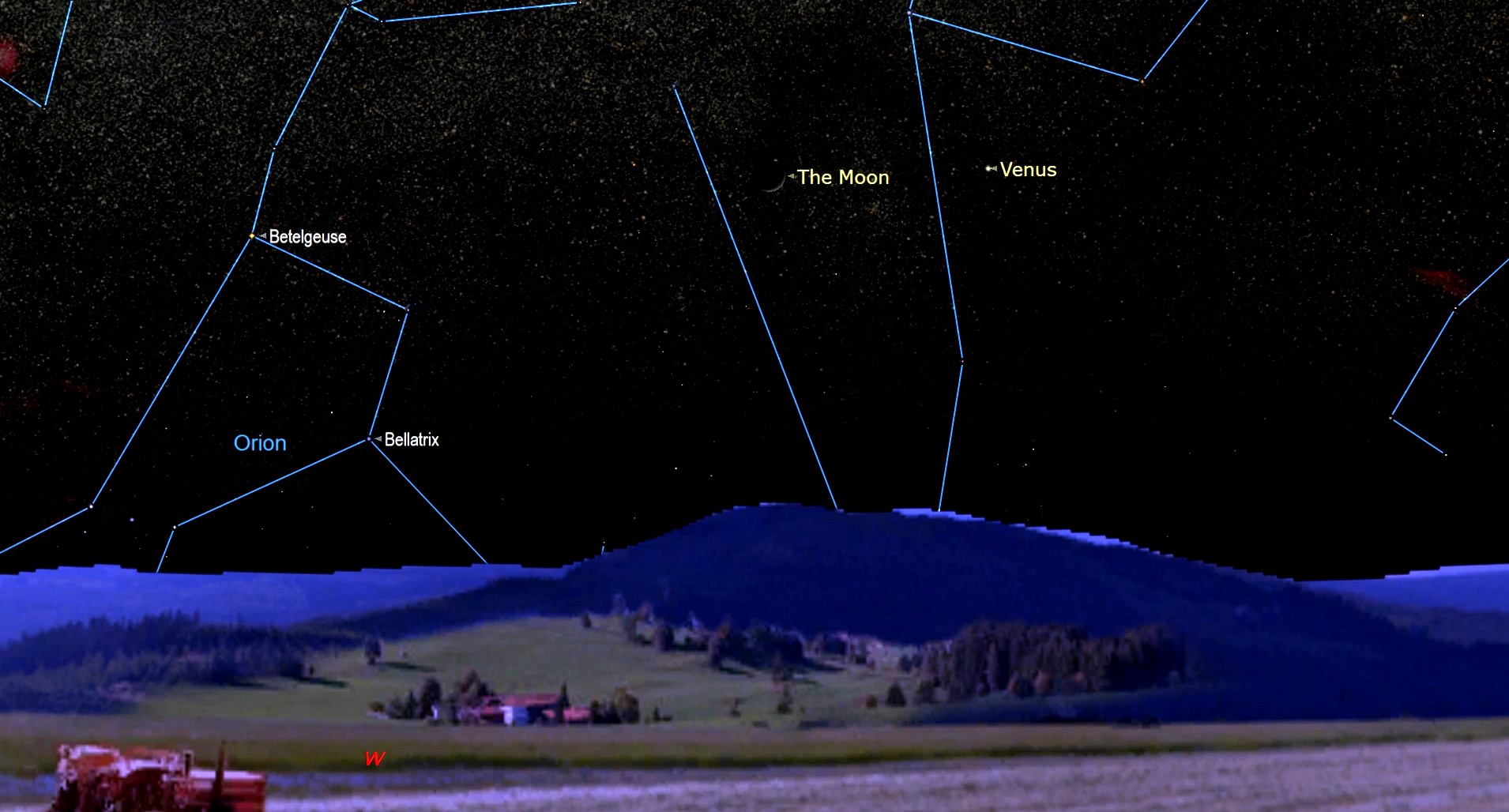

Although they are widely separated by 7 degrees, the two brightest objects in the night sky — the moon and Venus — still make for an eye-catching sight as they descend side-by-side in the April 26 west-northwest sky; their final readily visible evening encounter before Venus transitions into the morning sky in early June.

Editor's note: If you have an amazing skywatching photo you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, you can send images and comments in to spacephotos@futurenet.com.

- The brightest planets in April's night sky: How to see them (and when)

- What is a 'morning star,' and what is an 'evening star'?

- The 10 weirdest facts about Venus

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save at least 56% with our latest magazine deal!

All About Space magazine takes you on an awe-inspiring journey through our solar system and beyond, from the amazing technology and spacecraft that enables humanity to venture into orbit, to the complexities of space science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.

-

rod FYI, I was out tonight from 1930 until 2100 EDT viewing Venus et al. Earlier I created star charts using Starry Night and Stellarium 0.20.0 for my views. Here is a note from my log.Reply

"Sunset near 1931 EDT tonight or 7:31 PM. Clear skies, temperature near 10C, NW winds. The waxing gibbous Moon in Cancer was bright. I viewed Venus and the Pleiades using 10x50 binoculars and telescope at 40x. Venus nearly half-moon shape with some 20 or more stars of M45 visible in the eyepiece, especially after 2000 EDT or 8:00 PM. This would have made a great astrophoto. Tomorrow night, Venus is in M45 open star cluster near 2030 EDT. Using the binoculars, I could just see M44, the Beehive cluster in Cancer near the bright Moon. M42 in Orion, I could see four of the six stars in the Trapezium and some nebulosity at 40x with the telescope. The southern region of the Moon full of craters near Longomontanus crater region along the terminator line. Nothing like being under COVID-19 house arrest under the sky that is there tonight 😊---Rod -

John Pawl I heard the big sunset moon is an illusion before (referring to the video). . I've measured it myself often. When the full moon is high overhead, with my hand extended all the way out, I can easily cover it with my thumb. But when it's extra large on the horizon, with my hand fully extended, sometimes it takes 4 fingers to cover it.Reply

It's caused by refraction of the light as it hits our atmosphere, which is more pronounced the lower it is on the horizon. It's also why the moon & the sun are sometimes slightly oval when on the horizon. The refraction may be greater in some areas depending on the humidity, barometer, & pollution.

Many astronomers may not see much refraction because they work in areas with good visibility conditions, like low humidity, clean air, or low barometers, as near mountains or desserts.

Here in my polluted lowland city right next to the Great Lakes where it's often very humid, with a barometer above 30", on a rare extra large moon-set, 4 fingers won't cover it all, but depending on the weather, sometimes 2 fingers will cover it.

In a telescope, I can see Jupiter & Saturn shimmer, expand & contract as I'm watching it because of atmospheric refraction & distortions. We already know light refracts when passing from a vacuum, to dense atmosphere. The curvature of the earth & its atmosphere acts more like a lens when the moon is close to the horizon.

In fact, at the time of moon-set, sometimes the moon is already below the horizon, & what you are seeing is it's refracted image being bent by the atmosphere like a lens & prism. No illusion.

Mind your language.Refuting a comment with vulgarity isn't productive or civil.Moderator

Lutfij