Fingerprints of Venus Transformation May Be Hidden in Plain Sight

They could show its shift from habitable to hellish.

Venus may have once been a water-rich, Earth-like world whose raging volcanism morphed it into the overheated planet it is today. But it didn't become a nightmarish planet overnight. The fingerprints of its gradual shift may be present in some of the oldest surface features, hidden in plain sight.

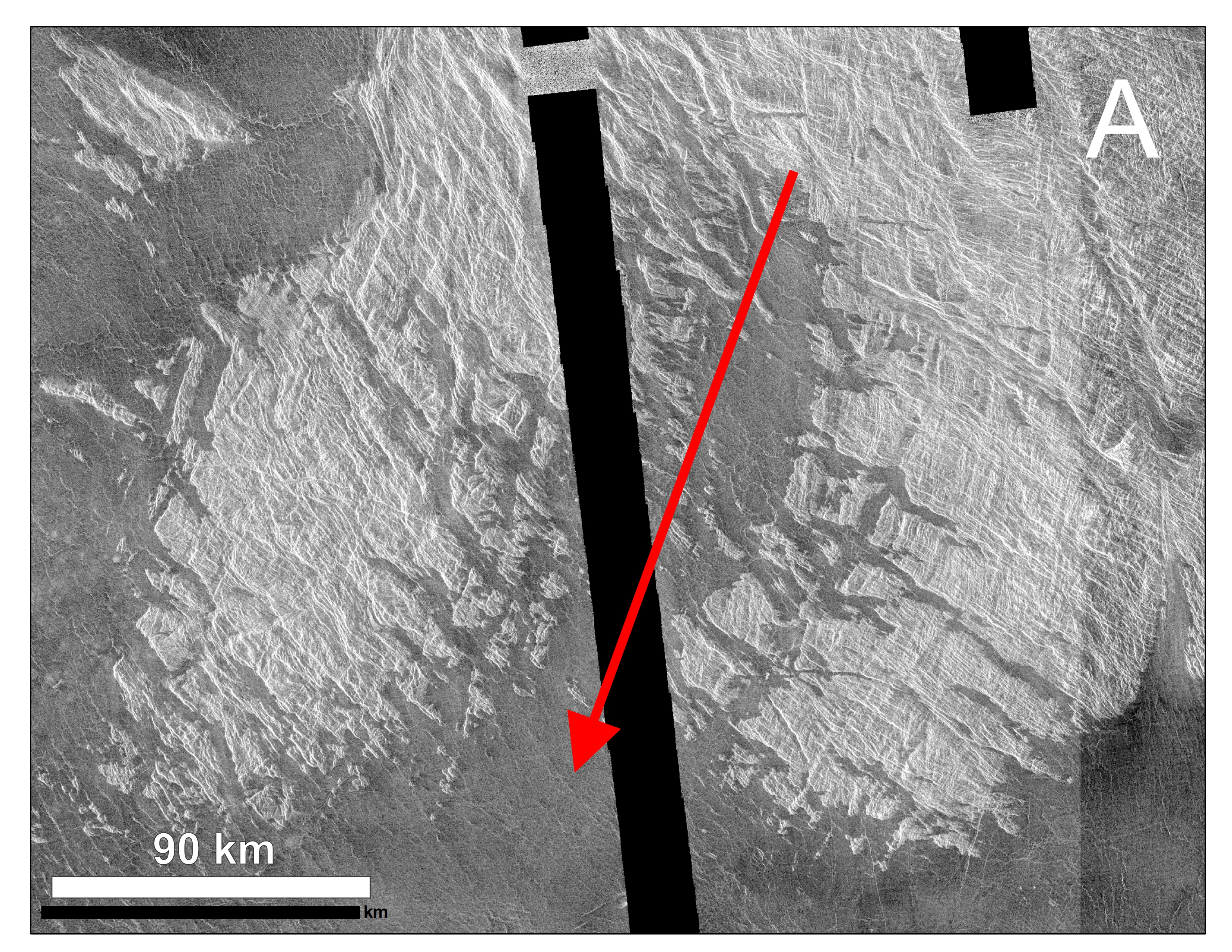

To understand what happened on the neighboring world billions of years in the past, researchers are turning to tesserae, complex geologic features on the Venusian surface whose origins remain a mystery. Tesserae are broad plains where rocks have been folded and broken by geologic activity.

"On Earth, such deformation of rocks does not usually occur at the surface — instead, such deformation typically occurs at depth, many kilometers below the surface," Richard Ernst, a geologist at Carleton University in Canada, told Space.com by email.

Related: What Would It Be Like to Live on Venus?

Since the tesserae of Venus lie on rather than under the surface, they must have been unearthed, Ernst said. Surface rocks above them could have shattered apart, revealing the tesserae beneath. Alternatively, interior rocks could have lifted the tesserae to the surface. In both situations, erosion of the tesserae would have played a significant role, and that's what Ernst wants his fellow scientists to be on the lookout for. He presented his research in March at the Lunar and Planetary Sciences Conference in The Woodlands, Texas.

According to Ernst, the tesserae likely formed during Venus' cooler period, when water running across the surface could have acted to erode the rocky formations. By hunting for signs of water erosion, Ernst thinks that it may be possible to track the warming of Venus over its lifetime, confirming the theory that the planet was once a more welcoming place.

"The search for erosional features in tesserae terrains is a key test of a hyper-global warming climate change for Venus," Ernst said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

A water-rich world

Today, Venus is a hellish place, with temperatures reaching an average of 864 degrees Fahrenheit (462 degrees Celsius). But at least one recent model predicts that, in its past, Venus may have been an Earth-like planet, with water running across its surface. What changed the paradisical world into a sweltering hotbox? Extreme volcanism.

Volcanoes dot the surface of Venus, and much of its surface is young. Previous studies have revealed signs of features that resembled enormous volcanic features on Earth known as large igneous provinces (LIPs). On Earth, LIPs result from enormous volcanic explosions with volumes of at least 24,000 cubic miles (100,000 cubic kilometers), enough to cover all of the United States to a depth of anywhere from 33 feet to 5 miles (10 meters to 8 kilometers).

"LIPs on Earth are associated with the breakup of supercontinents, catastrophic climate change including mass extinctions, and also some major ore deposit types," Ernst said.

Volcanic eruptions dump gases like carbon dioxide into the air. On Earth, plate tectonics work as part of the carbon cycle to help remove the gas from the atmosphere and trap it in rocks. Venus, however, doesn't have plate tectonics, so the carbon dioxide levels continue to rise, triggering a greenhouse effect that slowly warms the planet. Scientists have already identified a major phase of LIP-style eruptions that took place about 700 million years ago, kicking off the rise in temperatures.

"We should expect the beginning of the major time of volcanism should be the beginning of global warming," Ernst said.

Because the volcanism can take anywhere from 1 to 10 million years to heat the atmosphere, Ernst thinks that the resulting climate changes may have been preserved in the tesserae. He thinks Venus may host features suggestive of a water-rich past such as stream cuts, gravel deposits, mudslides, alluvial fans and deltas.

If these features exist, why has no one spotted them yet? Ernst thinks that it's because no one was looking for them.

"The idea of erosion on Venus has always been hard to imagine given the present-day superhot temperatures and the absence of free water," Ernst said.

With the emergence of the new model predicting that Venus was once cooler and water-rich, erosion features become easier to envision. Ernst suspects that having a model in hand that allows water to have once flowed across the surface will lead to more researchers identifying erosional features.

Enter tesserae. On a surface that was mostly recovered by volcanism, tesserae may provide some of the best links to the water-rich world of the past. They are among the oldest visible surface features and remain uncovered by the volcanic plains, Ernst said.

The next step toward identifying signs of erosion is more detailed mapping of the features on Venus. Erosion features would support the idea that the planet was water-rich when young. Dating those features would allow scientists a glimpse of how the planet changed over time.

"If we are able to identify erosion in the tesserae then we are essentially confirming the [recent] model that predicts that Venus had an Earth-like climate in the past," Ernst said.

- Should We Land on Venus Again? Scientists Are Trying to Decide

- Can Venus Teach Us to Take Climate Change Seriously?

- Bizarre Symmetrical Streaks Spied in Atmosphere of Venus

Follow Nola Taylor Redd on Twitter @NolaTRedd or Facebook. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd