The Vera C. Rubin Observatory: New view of the universe

The next era of astronomy will be defined by a wider view of the cosmos.

The next era of our investigation of the cosmos is about to be kick-started by the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, a ground-based telescope currently under construction on the El Penón peak of Cerro Pachón in northern Chile. The observatory is a federal project run by the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the U.S. Department of Energy.

The new observatory — named in honor of astronomer Vera Rubin — is scheduled to begin operations in October 2023, according to a statement published on the Rubin Observatory website. When it's up and running, Rubin will allow astronomers to consider some of the universe’s most pressing mysteries.

"There are four main scientific themes that have guided our design of the observatory," Vera C. Rubin director Steven Kahn, an astrophysicist at Stanford University in California, wrote in an email. "Cataloging all of the small moving objects in the solar system. Mapping the structure and evolution of the Milky Way. Investigating many kinds of stellar variability in the sky. And determining the nature of dark matter and dark energy, two of the greatest mysteries of modern physics."

Related: Vera Rubin: The astronomer who brought dark matter to light

Kahn said that the Rubin Observatory will also enable other kinds of studies that are independent of these areas. "We expect the observatory to make many discoveries — things we did not even know existed before," Kahn told All About Space.

A wider view of the universe

These four investigatory elements will be united under the umbrella of the decade-long Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST), according to an article from the Kavli Institute for Particle Physics and Cosmology, a joint operation of Stanford University and the U.S. Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory.

The LSST will build upon previous sky surveys that have formed the fundamental data pillars of astronomy for many years, systematically mapping the universe and providing insights that have shaped our understanding of the cosmos.

As impressive as these past surveys and the telescopes that conducted them have been, their view has been limited to a tiny fraction of the sky. This is one of the areas in which the Vera C. Rubin Observatory will really up the ante.

Originally named the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope in its initial proposal and in a paper posted in May 2008 on the preprint site arXiv.org, the design of the observatory’s main instrument — the Simonyi Survey Telescope (SST) — has been guided by three key watchwords: width, depth and speed.

This article is brought to you by All About Space.

All About Space magazine takes you on an awe-inspiring journey through our solar system and beyond, from the amazing technology and spacecraft that enables humanity to venture into orbit, to the complexities of space science.

"The Rubin Observatory will be very different from all the existing large telescopes," said Kahn. "Most telescopes are designed to make detailed investigations of individual objects — stars, galaxies and clusters of such objects. Rubin is designed instead to make a deep imaging survey of the sky over the entire Southern Hemisphere."

The key to this wide-field view is the telescope’s unique three-mirror design, which features a 27.6-foot-wide (8.4 meters) primary mirror. This design boosts what astronomers call the etendue of the system — a quality that is the product of the collecting area of the primary mirror and the field of view of the camera and describes how spread out the light in a system is.

"The Rubin Observatory will have an etendue more than 10 times larger than all previous facilities and any currently planned for development anywhere else in the world," said Kahn. "It is world-unique in that sense."

A camera like no other

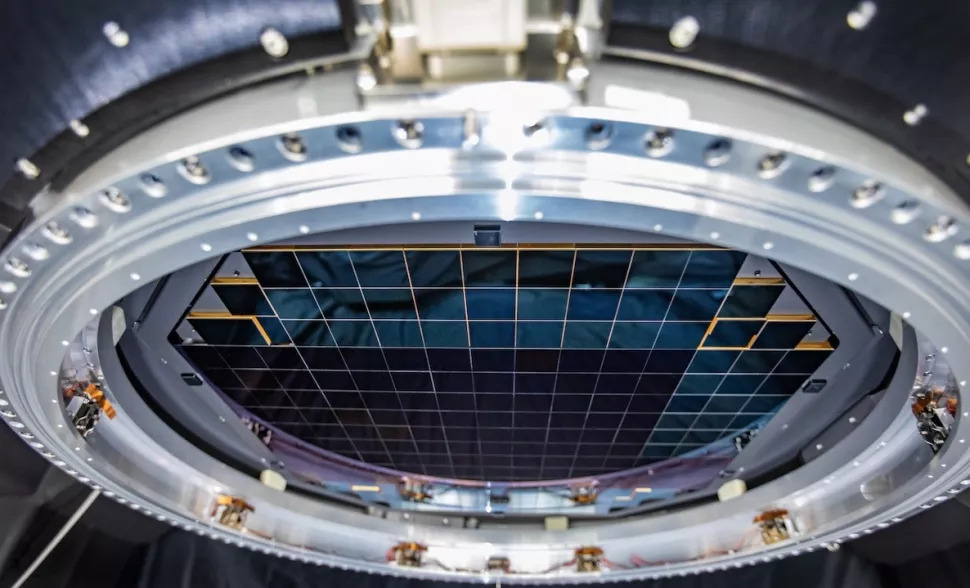

In order to obtain such high etendue, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory team had to combine this unusual three-mirror optical system with the use of a record-breaking piece of kit — the largest digital camera ever created. This SUV-sized camera is also the first in the world to have a 3.2-gigabyte capability, according to a news release published by the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in September 2020. Just one image produced by the camera would take over 350 4K TVs to display.

The camera will take one 15-second exposure of the sky every 20 seconds, enabling it to capture about 10,000 square degrees of the sky over the course of three nights. This grants the observatory the ability to both track moving objects like asteroids and record the changes in stars and events like supernovas. The movement of objects close to Earth and the rate at which objects like stars change occur over an extreme range of time periods. Fortunately, the observatory can survey the sky on timescales ranging from years down to around 15 seconds.

The Vera C. Rubin Observatory will also provide unprecedented depth by observing the universe in six different optical bands, with wavelengths ranging from 320 to 1,060 nanometers. That covers ultraviolet light, right through the visible light spectrum to infrared. As a result, the observatory will be able to image some extremely faint objects missed by previous surveys, according to Air & Space magazine.

"Rubin will obtain nearly 1,000 images of every part of the southern sky. By comparing images taken at different times, we can detect everything that moves in the sky and everything that varies in brightness," said Kahn. "By adding together those 1,000 individual images, we can obtain the deepest images of every part of the southern sky."

Related: 3,200 megapixels! The camera heart of future Vera Rubin Observatory snaps record-breaking 1st photos

How will Vera C. Rubin Observatory handle large amounts of data?

Collecting so many highly detailed images presents a major challenge, as it represents a huge amount of data that has to be handled — around 20 terabytes every night. Thus, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory requires another revolution just to process this sheer wealth of information.

"We also had to develop the technology to process all of that data, to store it, and to enable scientists to query it in order conduct their investigations," said Kahn. "All of that was new and is beyond state of the art."

For Kahn, part of the beauty of the project is that no one is quite sure what will be discovered in the data it provides. "We don’t know what we will find," he said. "That is the rationale behind building the experiment in the first place."

Kahn knows one thing for sure: the impact it will have on astronomy is tremendous. "Rubin will detect and catalog something like 20 billion galaxies, meaning for the first time we will know about more galaxies than there are people on Earth."

This number represents roughly 10% of all galaxies estimated to exist in the observable universe. "It will be a remarkable human achievement to be able to make such a record of our universe this way, equivalent in some respects to some of the first maps ever made of the entire Earth," Kahn told All About Space. "It is very exciting to be part of this project.

Additional resources:

- Read more about the Vera C. Rubin Observatory

- Discover more about the National Science Foundation (NSF)

- About the U.S. Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.