To decode dark energy, the Rubin Observatory will find millions of exploding vampire stars

"The large volume of data from Rubin will give us a sample of all kinds of Type Ia supernovas at a range of distances and in many different types of galaxies."

The Vera C. Rubin Observatory will soon open its eyes to the cosmos, and scientists predict it will detect millions of vampire stars exploding as they feed on their stellar companions.

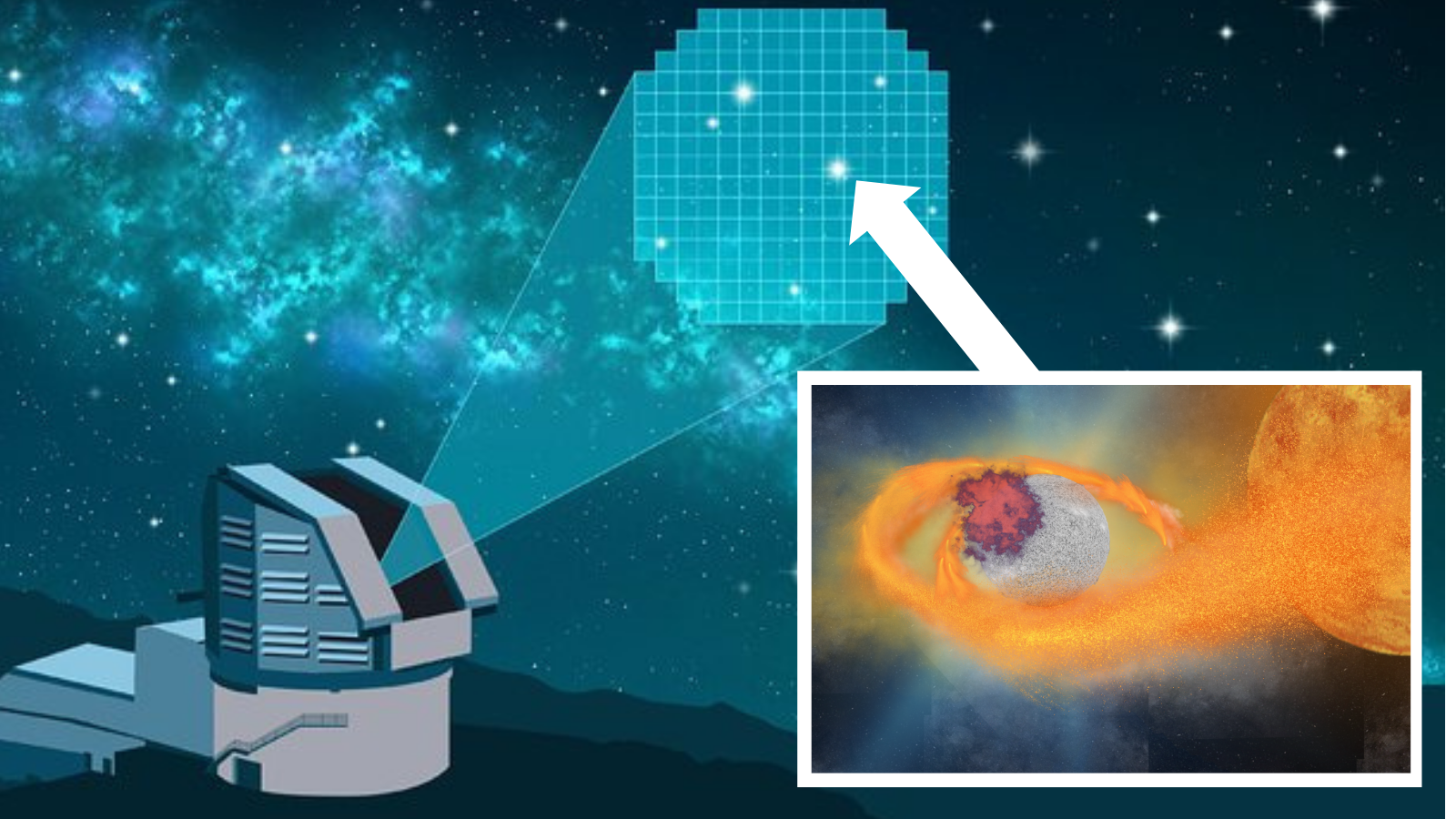

Currently under construction on the Chilean mountain Cerro Pachón, the Rubin Observatory is expected to begin its 10-year Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST) later this year.

An influx of data during this time, from so-called Type Ia supernovas, will be a boon to scientists investigating the mystery of dark energy, the unknown force that is driving the acceleration of the universe's expansion.

The light output of exploding white dwarf stars, which are the stellar corpses of stars with masses around that of the sun, is so uniform that astronomers can use it to measure distances. This uniformity means Type Ia supernovas are often referred to as "standard candles," serving as a vital rung on the "cosmic distance ladder."

Usually, it is difficult to tell if an astronomical body, like a star, is bright because it emits lots of light or because it sits closer to Earth. The fact that Type Ia supernovas emit a standard amount of light, however, means that astronomers can look at their brightnesses and colors and combine this with information about their host galaxies to calculate their true distances.

This, in turn, can reveal how much the universe has expanded because scientists can create milestones for certain distances in the universe.

"The large volume of data from Rubin will give us a sample of all kinds of Type Ia supernovas at a range of distances and in many different types of galaxies," Anais Möller, a team member of the Rubin/LSST Dark Energy Science Collaboration, said in a statement.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Why do white dwarfs blow their tops?

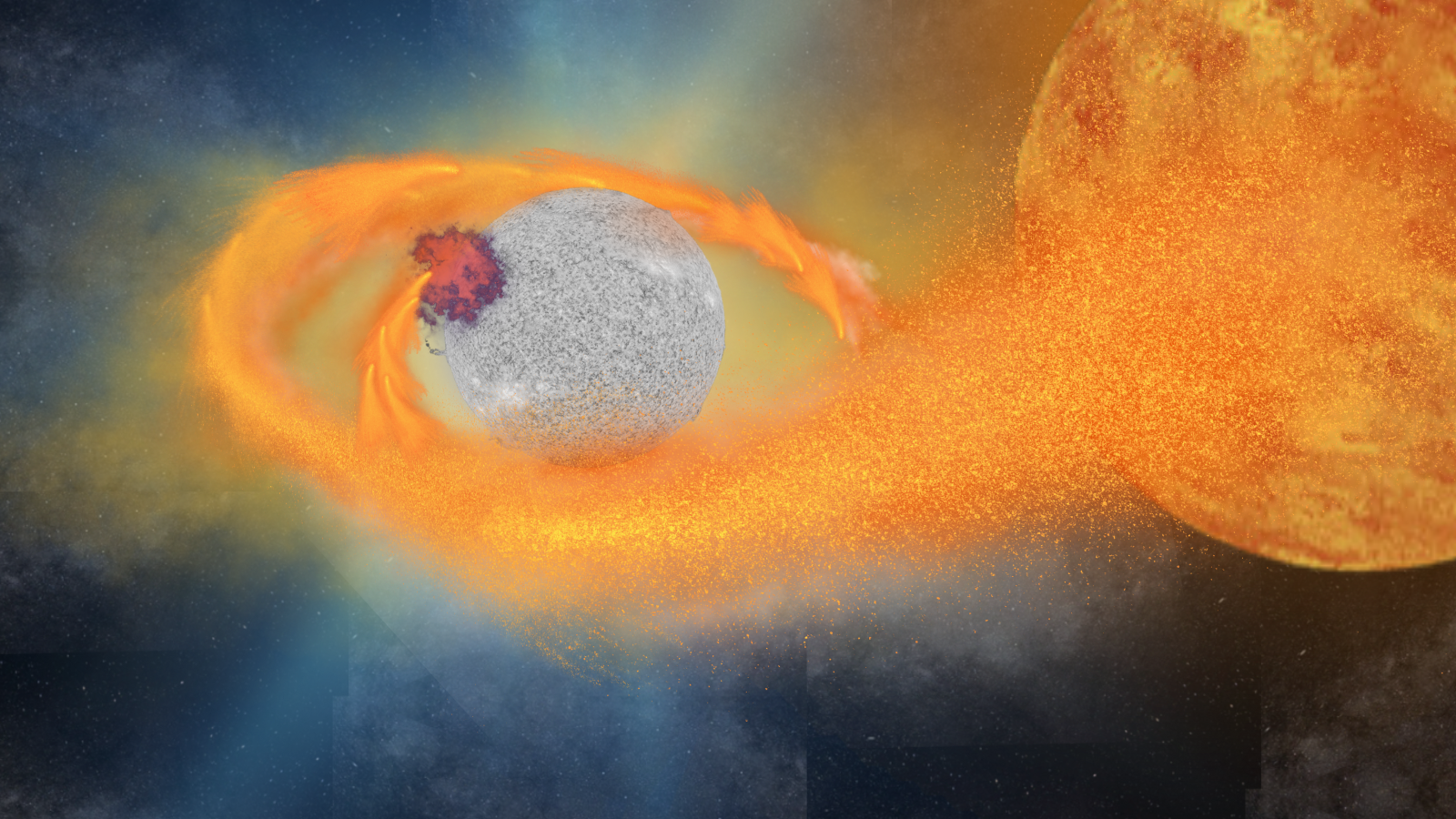

White dwarfs are born when stars with sun-like masses exhaust their fuel supplies needed for nuclear fusion reactions within their cores and thereby collapse under the influence of their own gravity.

Losing a great deal of mass as their outer layers are shed, these dead stellar cores end up under the so-called Chandrasekhar limit of around 1.4 solar masses. This means they can't go supernova.

The sun will undergo this process in around 5 billion years, ending its life as a lonely, cooling stellar ember.

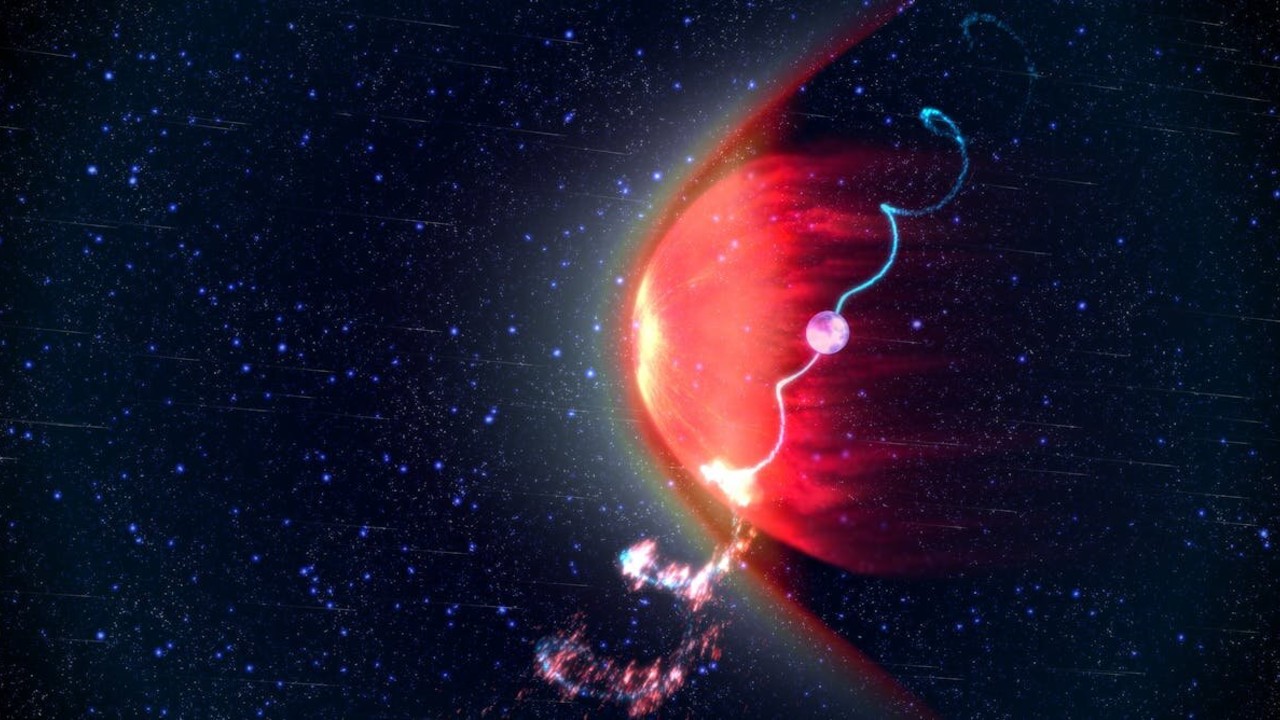

However, if the white dwarf progenitor star exists in a binary with another star, this stellar corpse can begin vampirically stripping material from its companion. That process will continue until the white dwarf has amassed enough stolen matter to creep over the Chandrasekhar limit.

Achieving this critical mass, white dwarfs erupt in Type Ia supernovas that usually obliterate them, though these explosions can, in rare cases, leave a shattered "zombie star" remnant.

Astronomers have spotted thousands of these explosive events. The problem, however, is that seeing a Type Ia supernova once or even twice isn't enough to build a picture of how its light varies over time. Yet, repeat viewings are difficult because these explosions appear without warning in the sky and then fade away.

Rubin will scan the sky over the southern hemisphere every night for 10 years, covering the entire hemisphere approximately every few nights hunting for objects with changing brightness. This rapid detection ability will make Rubin adept at spotting Type Ia supernovas and allowing astronomers to investigate them before they fade away.

Possessing data regarding more Type Ia supernovas located at different distances from Earth will allow scientists to build a better model of how dark energy is influencing the cosmos.

Rubin sheds light on dark energy

Type Ia supernovas have been intrinsic to the concept of dark energy since 1998 when two separate teams of researchers used these white dwarf eruptions to determine that the universe was expanding at an accelerating rate.

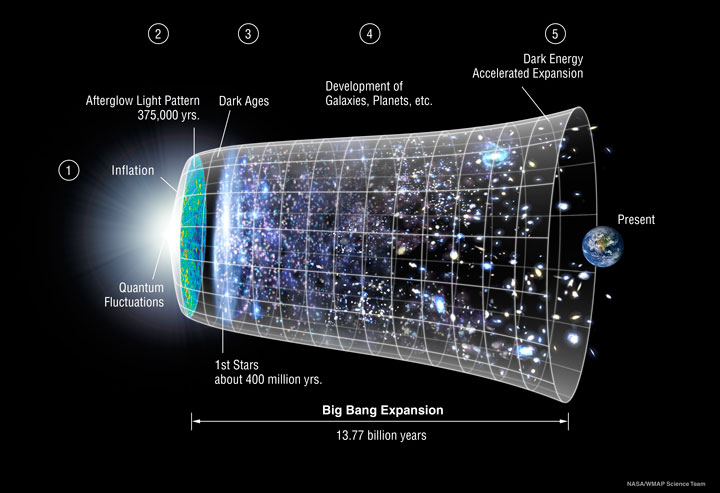

Since then, scientists have determined that dark energy dominates the universe, accounting for around 68% of the cosmic energy and matter budget. However, this wasn't always the case.

Whatever dark energy is, it seems to have only "kicked in" when the universe was between 9 billion and 10 billion years old. Before this, the universe had been dominated by matter — and before that, it had been ruled by the energy of the Big Bang.

The most robust model we have of the evolution of the universe, the Lambda Cold Dark Matter (LCDM) model, suggests that dark energy is constant. However, recent results from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) have suggested that isn't the case, hinting that the strength of dark energy is changing.

Rubin and the LSST could help resolve this issue by providing a larger sample of Type Ia supernovas over varying distances than scientists have ever before had at their fingertips.

"The universe expanding is like a rubber band being stretched. If dark energy is not constant, that would be like stretching the rubber band by different amounts at different points," Möller continued. "I think in the next decade, we will be able to constrain whether dark energy is constant or evolving with cosmic time.

"Rubin will allow us to do that with Type Ia supernovas.”

Astronomers will need to prepare themselves for a data deluge when Rubin begins scanning the sky over the southern horizon. It is estimated that Rubin will generate up to 10 million alerts embedded within 20 terabytes of data every night.

Software systems will process these alerts before being fired out to astronomers across the globe. Among the supernovas in the data will be other transient events such as variable stars and kilonovas, the violent collision between extreme dense stellar remnants called neutron stars.

"Because of the large volumes of data, we can't do science the same way we did before," Möller concluded. "Rubin is a generational shift. And our responsibility is developing the methods that will be used by the next generation."

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.