Come Thursday (March 19), we will have a change of the seasons: the occurrence of the vernal equinox, marking the official start of spring in the Northern Hemisphere and autumn in the Southern Hemisphere. In fact, it will be a rather auspicious occurrence: the earliest that the equinox has occurred nationwide in 124 years. More on that in a moment.

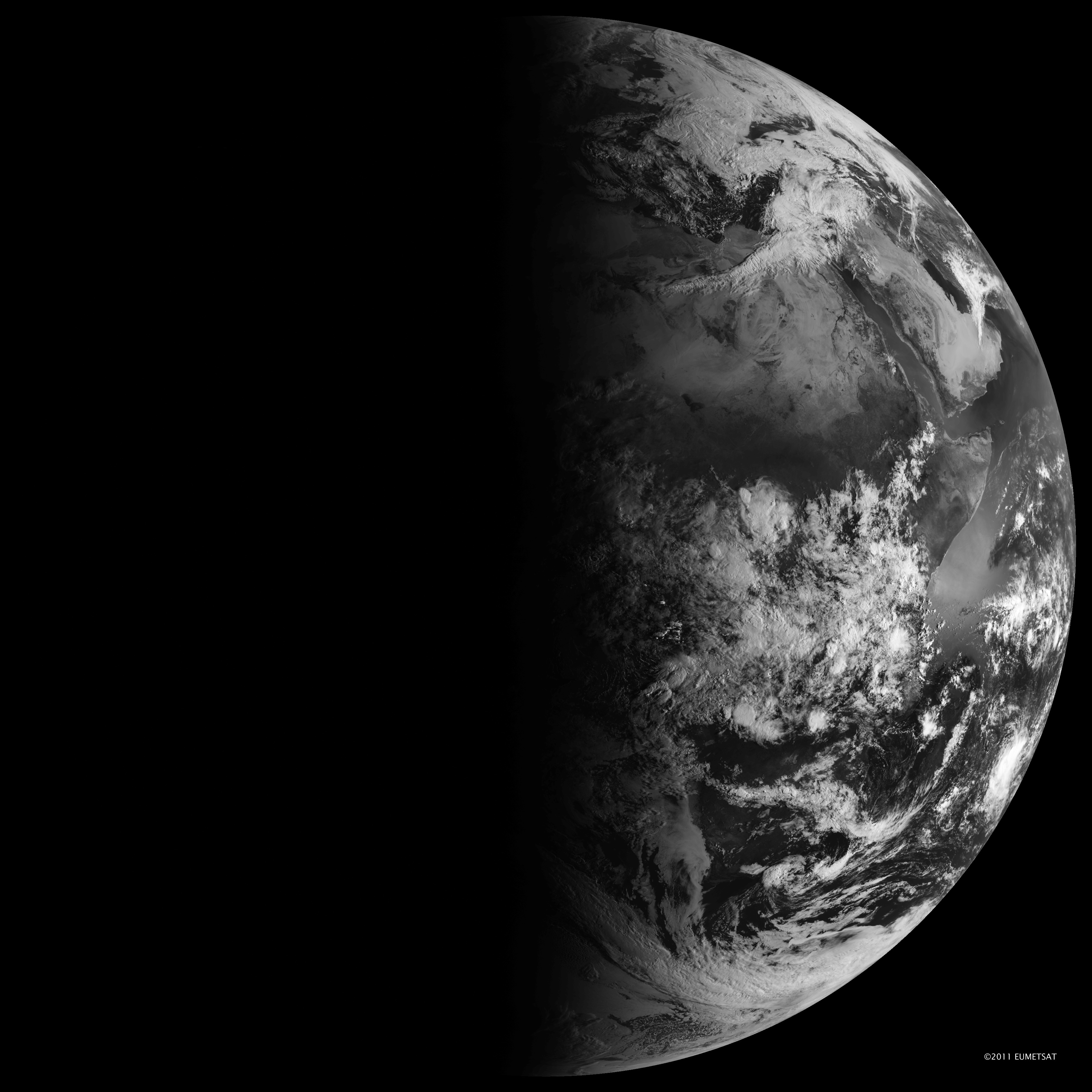

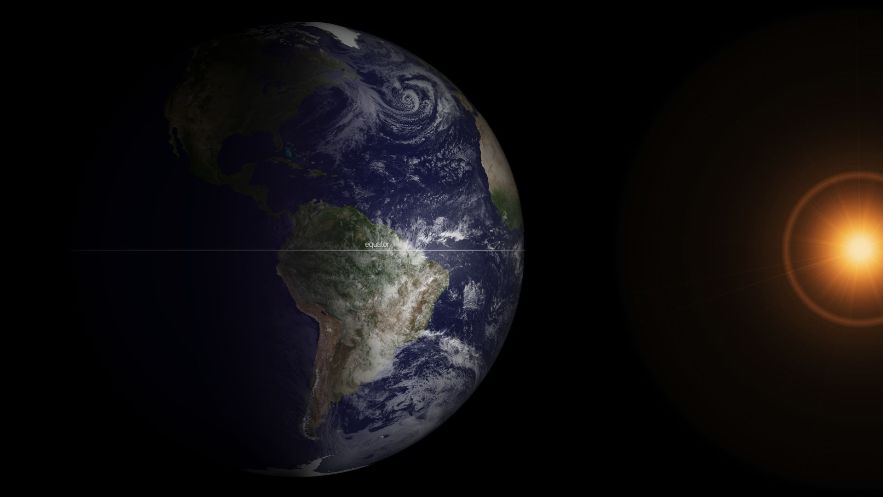

The exact moment of the equinox will occur Thursday night at 11:49 p.m. EDT (0349 GMT on March 20), according to the astronomy reference book "Astronomical Table of the Sun, Moon and Planets" (Willmann-Bell, 2016). At that time, the Earth will reach the point in its orbit where its axis isn't tilted toward or away from the sun. Thus, the sun will then be directly over a specific point on the Earth's equator moving northward. On the sky, it's where the ecliptic and celestial equator cross each other.

Related: Vernal equinox 2020: Google doodles celebrate changing seasons

More: Why the night sky changes with the seasons

A not-so-equal equinox

On the day of the equinox, the sun will appear to rise exactly east and set exactly west. Daytime and nighttime are often said to be equally long with the equinox, but this is a common misconception — the day can be up to 8 minutes longer, depending on your latitude.

The sun is above the horizon half the day and below for half — but that statement neglects the effect of the Earth's atmosphere, which bends the rays of sunlight (called refraction) around the Earth's curvature when the sun lies close to the horizon. But, because of this bending of the sun's rays, the disk of the sun is always seen slightly higher above the horizon than it really is.

In fact, when you see the sun appearing to sit on the horizon, what you are looking at is an optical illusion; the sun at that moment is actually below the horizon. So, we get several extra minutes of daylight at the start of the day and several extra minutes more at the end.

The supposed equality of day and night gives us the Latin name "equinox," which means "equal night." But in reality, thanks to our atmosphere, the day is longer than the night at the equinox. At the latitude of New York, for instance, day and night are roughly equal a few days before the equinox, on St. Patrick's Day (March 17).

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Sun overhead from the Emerald of the Equator

Astronomers can calculate the moment of the vernal equinox right down to the nearest second. This year it will occur on Thursday (March 19) at 11:49:28 p.m. EDT (0349 GMT on March 20). At that moment, the sun will appear directly overhead about 50 miles (80 kilometers) south of Gorontalo, a province of Indonesia — often referred to as the "Emerald of the Equator" — on the island of Sulawesi, on the equator in the Gulf of Tomini. In the days that follow, the direct rays of the sun migrate to the north of the equator and the length of daylight in the Northern Hemisphere will correspondingly appear to increase.

Why so early?

As was noted, this will be the earliest that the vernal equinox will occur across the contiguous United States in 124 years. There are two specific reasons for this variation of the date: leap years and daylight saving time.

When a leap year set us back a day

First, that 2020 is a leap year (meaning that the month of February had one extra day) is not the reason for the early arrival of this year's equinox. Rather, it is the leap year that we observed in the year 2000.

Let's look at the dates and times of the vernal equinoxes leading up to 2000. Note that each year the occurrence of the equinox happens about 6 hours (or one-quarter of a day) later in the calendar:

- 1996: March 20 at 3:03 a.m. EST (0803 GMT)

- 1997: March 20 at 8:54 a.m. EST (1354 GMT)

- 1998: March 20 at 2:54 p.m. EST (1954 GMT)

- 1999: March 20 at 8:46 p.m. EST (0146 GMT on March 21)

- 2000: March 20 at 2:35 a.m. EST* (0735 GMT)

In 46 B.C., Julius Caesar's consulting astronomer, Sosigenes, knew from Egyptian experience that the solar year was about 365.25 days in length. So to account for that residual quarter of a day, an extra day — leap day — was added to the calendar every four years. Unfortunately, the new Julian calendar was 11 minutes and 14 seconds longer than the actual solar year. By the year 1582 — thanks to the overcompensation of observing too many leap years — the calendar had fallen out of step with the solar year by 10 days.

It was then that Pope Gregory XIII stepped in and, with the advice of his own astronomer, Christopher Clavius (1538-1612), produced our current "Gregorian" calendar. First, to catch things up, 10 days were omitted after Oct. 4, 1582, making the next day Oct. 15. In order to better adjust the new calendar format to more closely match the length of the solar year, most century years (such as 1700, 1800, 1900) — which in the old Julian calendar would have been observed as leap years — were not. The exceptions were those century years equally divisible by 400. That's why 1700, 1800 and 1900 were not leap years.

But 2000 was a century year, evenly divisible by 400, so it was observed as a leap year. Had we skipped the leap year in 2000 (as in 1900), then the vernal equinox in 2000 would have occurred a day later, on March 21 at 2:35 a.m. EST (0735 GMT).

Hence, the reason we have an asterisk next to that date.

So, thanks to February having an extra day in 2000, the date of the equinox slipped back a day to March 20.

Daylight saving time delayed the equinox in the East

Because the solar year is not exactly one-quarter of a day longer than the 365-day calendar year, but a little bit less than one-quarter (24.22%) of a day, the occurrence of the equinox comes about 47 minutes earlier (on average) every four years:

- 2000: March 20 at 2:35 a.m. EST (0735 GMT)

- 2004: March 20 at 1:48 a.m. EST (0648 GMT)

- 2008: March 20 at 1:48 a.m. EDT (0548 GMT)*

- 2012: March 20 at 1:14 a.m. EDT (0514 GMT)

- 2016: March 20 at 12:30 a.m. EDT (0430 GMT)

- 2020: March 19 at 11:49 p.m. EDT (0349 GMT on March 20)

The asterisk (*) indicates that the United States and Canada had begun observing daylight saving time on the second Sunday in March rather than the first Sunday in April, a practice that began in 2007. In 2000, only those in the Pacific time zone (as well as in Alaska and Hawaii) observed the equinox on March 19. In 2004, 2008 and 2012, those time zones again saw spring arrive on March 19, along with people on Mountain Time.

In 2016, those in the Central time zone celebrated a March 19 arrival. Were we still on the old system (when daylight saving time did not begin until early April), we would have been on standard time in 2016, and those in the eastern parts of North America, too, would have observed the equinox on March 19 (at 11:30 p.m. EST), but daylight time pushed that off for another four years. Finally this year, from coast-to-coast, spring will arrive on March 19 — the earliest in 124 years.

And as a point of record: In 1896, the vernal equinox arrived on March 19 at 9:29 p.m. EST (0229 GMT on March 20).

Astronomical vs. meteorological spring

Truth be told, there are really two springs: astronomical spring and meteorological spring.

Astronomical spring is measured by the vernal equinox, but that's only a marker in the big flow of time, set up by astronomers — a sidereal milepost, accurate as a ticking clock but only approximately timing the changing of the seasons.

Meteorological spring supposedly has already started as of March 1, and runs through the end of May, according to Accuweather. In truth, however, meteorological spring ignores the clock and calendar, makes its own rules and creates a festival of song and blossom, all in its own time.

The crocuses, early robins and other vernal phenomena pay no attention to the hairsplitting details marking the astronomical arrival of the vernal equinox. They all have their own way of knowing when spring truly begins.

- Season to season: Earth's equinoxes & solstices (infographic)

- Vernal equinox: First day of spring seen from space (photo)

- Why the autumnal equinox doesn't fall on the same day every year

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save at least 56% with our latest magazine deal!

All About Space magazine takes you on an awe-inspiring journey through our solar system and beyond, from the amazing technology and spacecraft that enables humanity to venture into orbit, to the complexities of space science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.