How do viruses affect astronauts in space? Here's what we know so far.

Even astronauts can't escape viruses, but we still don't know much about how these microbes might affect humans in space.

About 15 hours into the Apollo 7 mission, Cmdr. Walter Schirra Jr. came down with a head cold, and before long, all three mission astronauts were sick.

Mucus collected in their heads without any gravity to weigh it down, which made the astronauts extremely uncomfortable. They even refused to wear their helmets during landing. The astronauts were concerned that with their congestion, the change in pressure as they entered the Earth's atmosphere would damage their sinuses or burst their eardrums. Ultimately, they landed safely without helmets, although ground control was not happy that the astronauts had refused to wear the gear.

After this incident, NASA decided that all astronauts must quarantine for two weeks before launch, and since then, there have been no recorded viral outbreaks in space. However, scientists still don't fully understand how viruses may affect, and potentially threaten, astronauts in space.

Related: What quarantine is like for an astronaut

In a new mini-review paper published online Feb. 11 in the journal Astrobiology, researchers at the German Aerospace Center's Institute of Aerospace Medicine explored what we know so far about viruses in space habitats. In addition to the many other ways that going to space affects human health, the researchers said it's crucial to understand more about viruses in space, especially as astronauts spend more time there, including on a potential future mission to Mars.

"If a tiny new virus can start something like [the COVID-19 pandemic] on Earth, imagine how it would be on a space station," first author Bruno Pavletić, a space microbiology researcher at the German Aerospace Center, told Space.com.

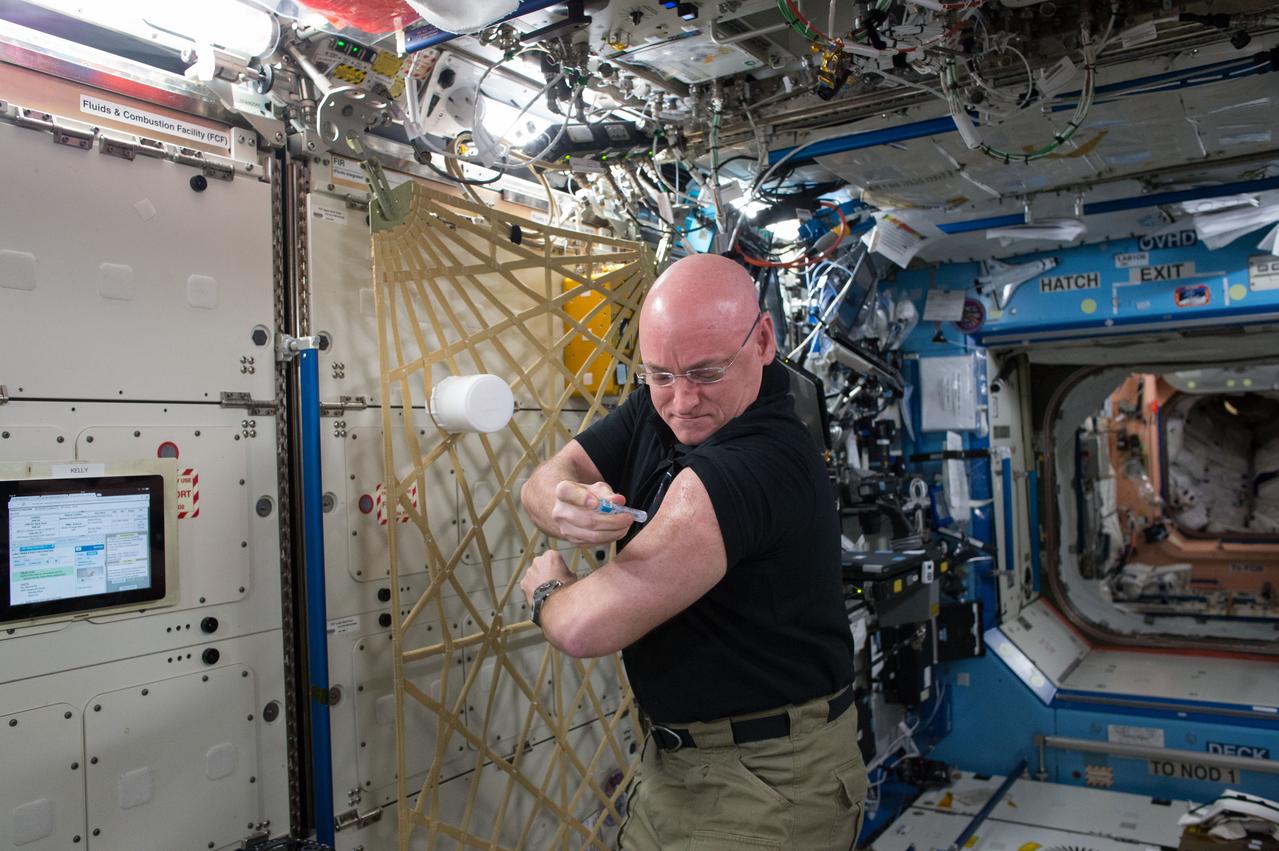

First, the team examined research on the abundance and diversity of viruses in space environments. Though the team examined a variety of other research in their paper, in this first section they examined the only study, published in the journal Nature Communications in 2019, that has looked at viruses aboard the International Space Station. In that study, researchers used swabs of surfaces on the space station to sequence viral genomes and identify different viruses.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The vast majority — about 95% — of the viruses they found were so-called bacteriophages, which are viruses that infect bacteria. Another 1% of the viruses infected plants or algae, or were unidentifiable. But about 4% of the viruses were human or animal viruses, including papillomaviruses, a family of viruses that can cause warts; herpesviruses, a family of viruses that can cause cold sores as well as illnesses like chickenpox and mononucleosis; and adenoviruses, which cause a wide range of illnesses, including the common cold.

Pavletić said the findings show that, despite quarantine procedures, pathogens still make it to outer space.

"We wanted to emphasize, first of all, that viruses can get out there," he said.

Reactivated viruses

The researchers also explored ways the space environment could affect viruses and their human hosts. For instance, research shows that some viruses that are dormant inside astronauts' bodies — meaning they are still present in the body but do not replicate or cause symptoms — may sometimes reactivate in space. Reactivated viruses, whether in space or on Earth, can cause symptoms, though they don't always, and can become contagious.

These viruses include herpesviruses such as the varicella zoster virus, which causes chickenpox and, when the dormant virus is reactivated in someone who has previously been infected with the virus, can cause shingles in adults. Testing done on astronauts in the space shuttle programs and more recent space station missions show that this virus, among others, reactivated in some astronauts.

In a few cases, astronauts have had skin rashes, from reactivated herpesviruses. Though tests have shown that multiple herpesviruses had been reactivated, including varicella zoster virus, it is unclear which might have caused the rashes.

Though scientists are not sure exactly what causes this reactivation, the study researchers wrote that it could be ultraviolet radiation exposure, which has been shown to reactivate viruses in rodents and suppress the immune system of humans and other animals. Virus reactivation also could be influenced by factors such as differences in humidity and gravity, as well as dehydration and sleep deprivation, both of which astronauts often experience in space.

"We were not designed to be [in space]," said study co-author Ana Nascimento, a virologist at the German Aerospace Center. "We are getting all of these factors at the same time."

Because of the unique combination of these factors in space, Earth-based research on this topic has limitations, Pavletić said. Even if research on Earth simulates some of these factors — such as humidity, radiation and microgravity — other influences, such as the specific physical and psychological stress that astronauts experience in space, could affect astronauts' immune systems, which means it might not present a full picture of how viruses affect humans in space.

Future research should focus on keeping astronauts as healthy as possible, which could look very different from keeping people healthy on Earth, said study senior author Ralf Moeller, head of the Aerospace Microbiology Research Group at the German Aerospace Center's Institute of Aerospace Medicine.

"Maybe we need to establish a baseline: What does health mean on Earth, and what does health mean in space?" Moeller told Space.com. "We're talking about two absolutely different topics."

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Rebecca Sohn is a freelance science writer. She writes about a variety of science, health and environmental topics, and is particularly interested in how science impacts people's lives. She has been an intern at CalMatters and STAT, as well as a science fellow at Mashable. Rebecca, a native of the Boston area, studied English literature and minored in music at Skidmore College in Upstate New York and later studied science journalism at New York University.