Voyager 2 Transformed Our Ideas of Jupiter's Moons 40 Years Ago

It was 40 years ago today that a NASA spacecraft revealed strong evidence that an icy moon of Jupiter may be able to host life.

Voyager 2 flew by the Jupiter system on July 9, 1979, and discovered a host of surprises — including a series of cracks on the surface of one Jupiter's moons, Europa. The scenes in the spacecraft's pictures reminded scientists of a crust floating above a thin water ocean, according to NASA, but with only a few hours at Jupiter, the plucky probe couldn't solve the mystery.

It was only after the Galileo mission operated at Jupiter from 1995 to 2003 that scientists gathered enough evidence to hypothesize that the Jovian moon indeed hides a subsurface global ocean that could be friendly to microbes, depending on what's in the environment. The concept is so compelling it's even hit Hollywood, with the monster movie "Europa Report" (2013) speculating what might lurk under the surface.

Related: Voyager at 40: 40 Photos from NASA's Epic 'Grand Tour' Mission

Galileo and its successor spacecraft, Cassini, at Saturn, together showed a host of similar icy moons at Jupiter and Saturn that may well sport internal oceans — Enceladus, Titan and Callisto to name a few. And in the last few years, the Hubble Space Telescope showed intriguing evidence of Europa periodically spurting water into space.

NASA is considering sending two probes to Europa in the 2020s. However, internal reports released earlier this year indicated that both missions are in trouble due to technical and budgetary issues. This week, however, the agency looked back at one of the two missions that started this new round of interest in Europa: Voyager 2.

That spacecraft launched on Aug. 20, 1977, a few weeks ahead of its twin, Voyager 1. (Voyager 2 was launched first to hit a favorable trajectory to continue to Uranus and Neptune if funding continued, according to BBC Science Focus Magazine.) Both spacecraft took advantage of a rare alignment of the outer planets to swing between destinations in the solar system, starting with Jupiter and Saturn.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

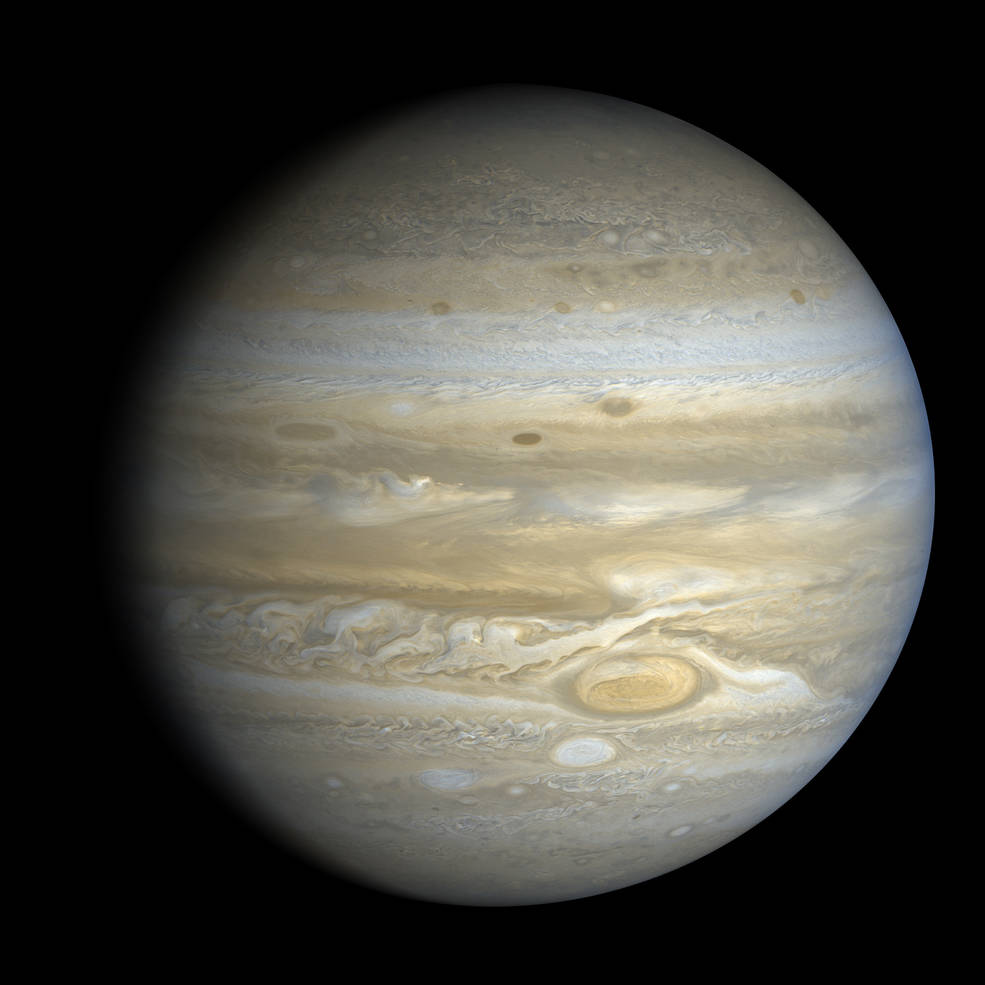

Voyager 2's first distant images of Jupiter flowed back on April 24, 1979, and the probe continued taking images and data all the way through Aug. 5 of that year, NASA said. During this 3.5-month period, the spacecraft sent back 17,000 images of the planet and its moons.

Voyager 1 had reached Jupiter's neighborhood first, but the latter spacecraft confirmed several of its twin's discoveries and made its own in addition. Voyager 2 was directed to fly relatively close to several Jovian moons as it approached Jupiter. The largest of Jupiter's moons, which are visible even in a small backyard telescope on Earth, are Ganymede, Callisto, Io and Europa.

To give a sense of how close Voyager 2 went to some of these moons, you can compare it to the distance between Earth and our own moon, which is about 238,855 miles (384,400 kilometers). Voyager 2 flew by Europa and Callisto at about half that distance: 127,900 miles (205,000 km) from Europa and 133,600 miles (215,000 km) from Callisto. The spacecraft made a much closer flyby of Ganymede, at just 38,600 miles (62,100 km).

Voyager 2's work, in concert with other observations made before and after its journey, helped scientists gather evidence that each of these moons is an ocean world. The spacecraft also got a very distant look at Io on its way out, confirming Voyager 1's observations of active volcanoes, which puzzled planetary scientists at the time.

The key to all of these active moons is Jupiter's immense gravity. The largest planet in the solar system, Jupiter is so big that about 1,300 Earths could fit inside of it. As these natural satellites orbit around the gas giant, tidal forces from Jupiter flex the moons' insides and keep them warm. This phenomenon maintains the hypothesized global oceans on Europa, Callisto and Ganymede and fuels volcanoes on Io.

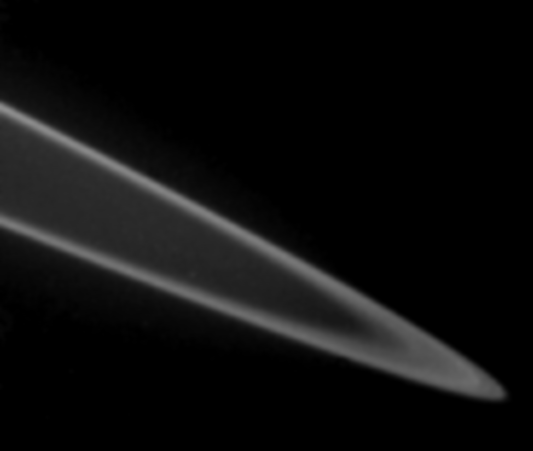

Voyager 2 did much more at Jupiter's system. Pictures looking back at the planet as the spacecraft departed confirmed that thin rings surround Jupiter, just as Voyager 1 had seen. Voyager 2 also discovered a moon, which Voyager 1 had not seen, orbiting just outside the rings; the moon was later called Adrastea.

Voyager 1's journey took it past Saturn and far up above the plane of our solar system, while Voyager 2 kept swinging from planet to planet. That spacecraft passed by Uranus in 1986 and Neptune in 1989, before continuing its voyage out of the solar system. Voyager 1 entered interstellar space in 2012 and Voyager 2 in 2018.

Both spacecraft continue to transmit data back to Earth. They are expected to continue sending science data until about 2025, when their nuclear power supplies will become too weak to support any instruments, according to NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

- Voyager 2: Sailing Among Giant Planets

- Jupiter's Great Red Spot: Photos of the Solar System's Biggest Storm

- Photos: Europa, Mysterious Icy Moon of Jupiter

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.