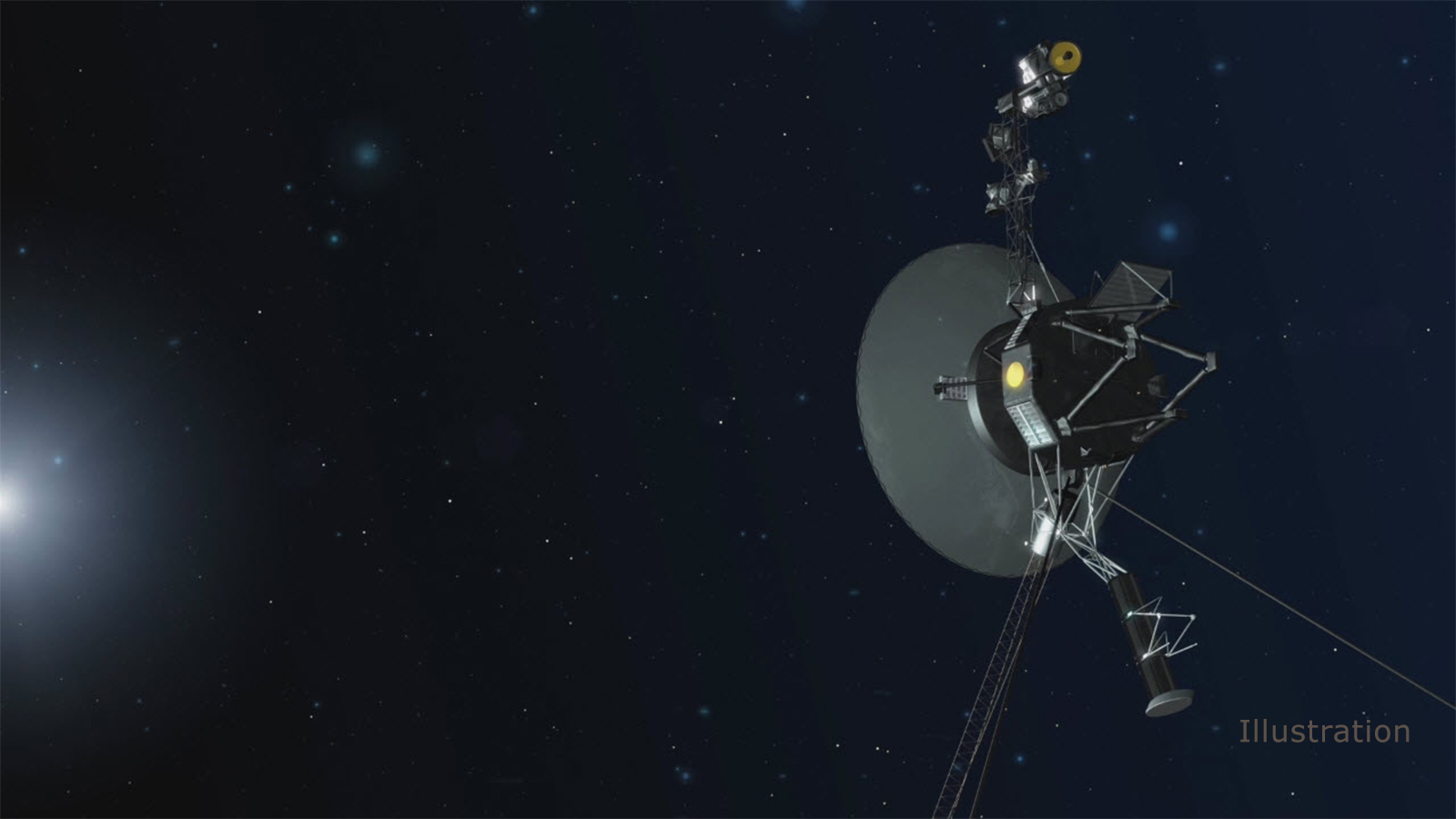

NASA's Voyager Spacecraft May Have 5 Years Left to Explore Interstellar Space

The twin Voyager probes are the ultimate spaceflight overachievers, but everyone knows their run can't last forever.

Right now, it's looking like the grizzled spacefarers have about five years before they fall silent, when they'll be no longer able to send word of their adventures back to the humans who have eagerly awaited their telegrams for 42 years and counting. The Voyagers' journey will continue indefinitely, but we will no longer travel with them.

"It's cooling off, the spacecraft is getting colder all the time and the power is dropping," Ed Stone, the mission's project scientist and a physicist at Caltech, said during a news conference held Oct. 31 in conjunction with the publication of a handful of new scientific papers. "We know that somehow, in another five years or so, we may not have enough power to have any scientific instruments on any longer."

Related: Voyager 2's Interstellar Trip Deepens Mysteries Beyond Solar System

Their success is unprecedented, even by NASA standards; the mission has lasted for two-thirds of the agency's existence. "We're certainly surprised but also wonderfully excited by the fact that they do [still work]," Stone said. "When the two Voyagers were launched, the Space Age was only 20 years old, so it was hard to know at that time that anything could last over 40 years."

Just as stunning as the spacecraft's longevity has been the longevity of a handful of instruments on board the probes. Four instruments on Voyager 1 continue to work; their twins and a fifth instrument are still gathering data on Voyager 2.

Stamatios Krimigis, a space scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory and the principal investigator of the mission's low-energy charged particles experiment, explained that the devices were designed to last just four years, during which they would need to conduct 250,000 turns of a motor (dubbed "steps") to take measurements. Both versions of the experiment are still running.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"That device has been stepping every 192 seconds for the last 42 years," Krimigis said during the news conference. "It's close to 8 million steps, and we're absolutely amazed that it's still working."

The Voyager spacecraft launched two weeks apart in 1977, taking slightly different trajectories past Jupiter and Saturn. Then, the probes parted ways. Voyager 1 scouted out Saturn's moon Titan and then made a beeline out of our solar system; Voyager 2 took a more leisurely route, giving humans our only look at Uranus and Neptune.

Related: NASA's Voyager 2 Went Interstellar the Same Day a Solar Probe Touched the Sun

Their longevity has translated to speed and distance that are difficult to fathom. Both spacecraft are traveling at more than 30,000 mph (48,000 km/h). On NASA's tracking page for the mission, each spacecraft's odometer ticks up by 10 miles (16 kilometers) or more twice a second, a constant churn that makes the passage of time suddenly excruciating.

But the Voyagers are traveling at nowhere near the speed of light (186,000 mps, or 300,000 km/s), as their messages do. And yet, it takes nearly 17 hours for messages from Voyager 2 to travel back to Earth and more than 20 hours for those sent by Voyager 1. A whole meme cycle can roil the internet here on Earth between a message's dispatch and its arrival.

The probes' distance only makes them more compelling emissaries. A year ago, the mission checked off yet another achievement when Voyager 2 followed its twin through the bubble that surrounds our solar system. In just a couple of hours, Voyager 2 went from being surrounded by material born in the sun to being bathed by the local neighborhood — a transition Voyager 1 had made in 2012.

Stone and Krimigis spoke to mark the publication of the first batch of scientific papers comparing the two crossings. The twin spacecraft's transitions to interstellar space have been similar but not identical, variations on a theme that humans have no concrete plans to experience again anytime soon. Unless something very dramatic happens in the universe around us, Pluto veteran New Horizons, like the Pioneer spacecraft before it, will fall silent long before it escapes our little bubble.

What the Voyager mission has made clear, the scientists speaking at the news conference said, is that two crossings are hardly enough to begin understanding this bubble — and that, nevertheless, the spacecraft have completely changed what we know about it.

"We had no good quantitative idea of how big this bubble is that the sun creates around itself," Stone said. "We didn't know how large the bubble was, and we certainly didn't know that the spacecraft could live long enough to reach the edge of the bubble and leave the bubble and enter interstellar space, at least nearby interstellar space."

And now, of course, they do.

"This has really been a wonderful journey," Stone said.

- Voyager at 40: 40 Photos from NASA's Epic 'Grand Tour' Mission

- What Spacecraft Will Enter Interstellar Space Next?

- Photos from NASA's Voyager 1 and 2 Probes

Editor's note: This story has been updated to correct a value for the speed of light. Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.