'Warm Jupiter' exoplanet 300 light-years away found by amateur astronomers

"Researching as a citizen scientist is something I highly recommend to anyone who gazes at the night sky with awe and wonder."

NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) has so far spotted over 7,000 planets around other stars, but only a fraction of them have been confirmed to be real detections — the rest could be intriguing planets awaiting discovery or simply noise. Unfortunately, however, neither TESS nor other professional telescopes have the luxury of time to study every suspect in detail.

This is where amateur astronomers come in.

Amateur astronomers often take on that time-consuming work, using backyard telescopes for follow-up observations necessary to validate the existence of candidate planets. And in doing so, they also spark new research. In fact, a group of citizen scientists, which included a high school student from California, confirmed one of TESS' candidate planets using backyard telescopes. The world is part of a relatively new class of exoplanets known as "warm" Jupiters.

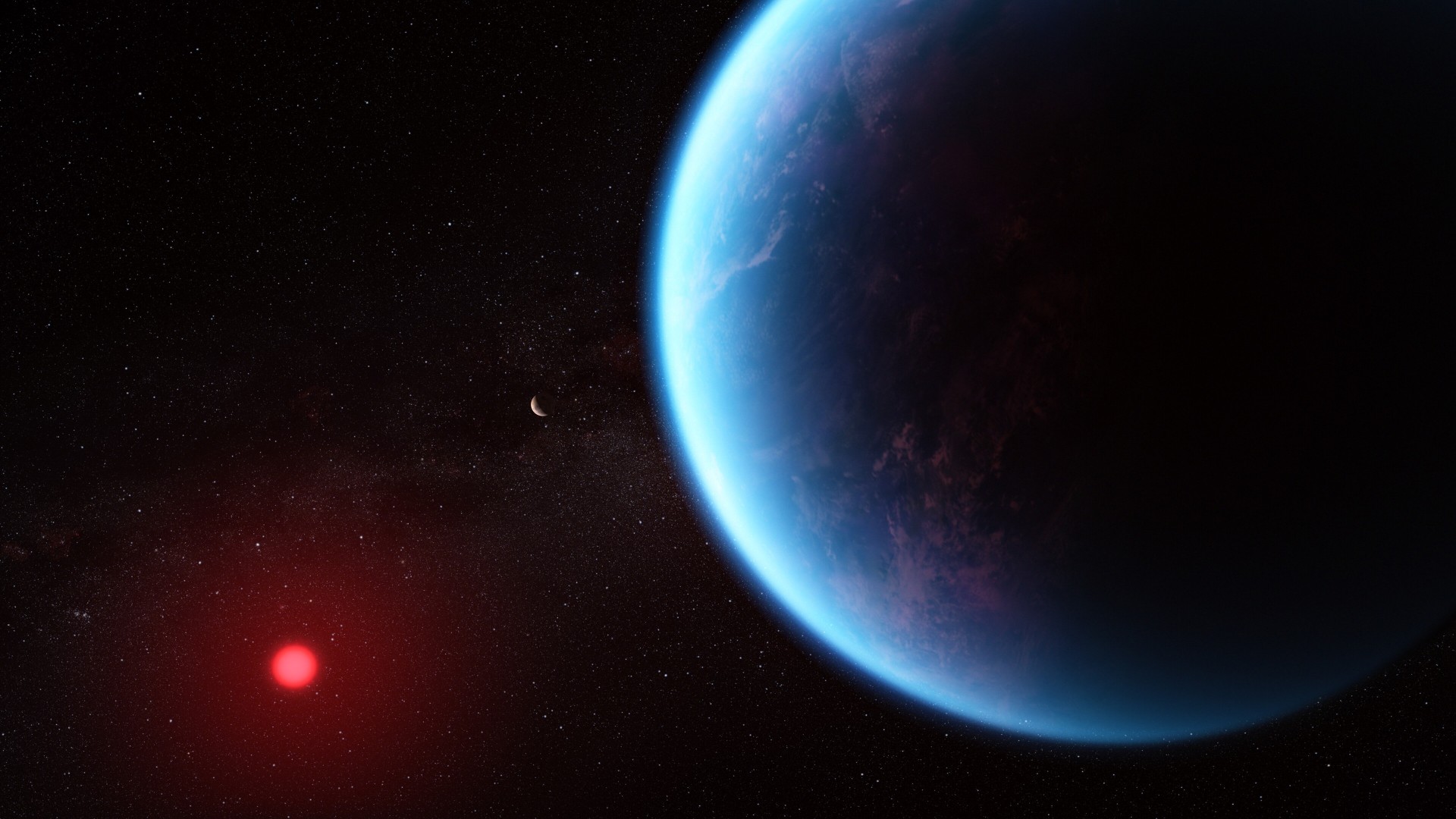

The toasty planet is in a transitional stage between a "cold" Jupiter like our own Jupiter is and a "hot" Jupiter, which is a type of exoplanet that orbits blisteringly close to its star. Astronomers say piecing together the newly found world's history would allow them to learn more about how giant planets evolve, and specifically whether hot Jupiters form very close to their stars or form farther out before later migrating inward. Ultimately, knowing more about all kinds of Jupiters can reveal more about the history of our own Jupiter — and indeed the solar system as a whole.

Related: 25 years of exoplanet hunting hasn't revealed Earth 2.0 — but is that what we're looking for?

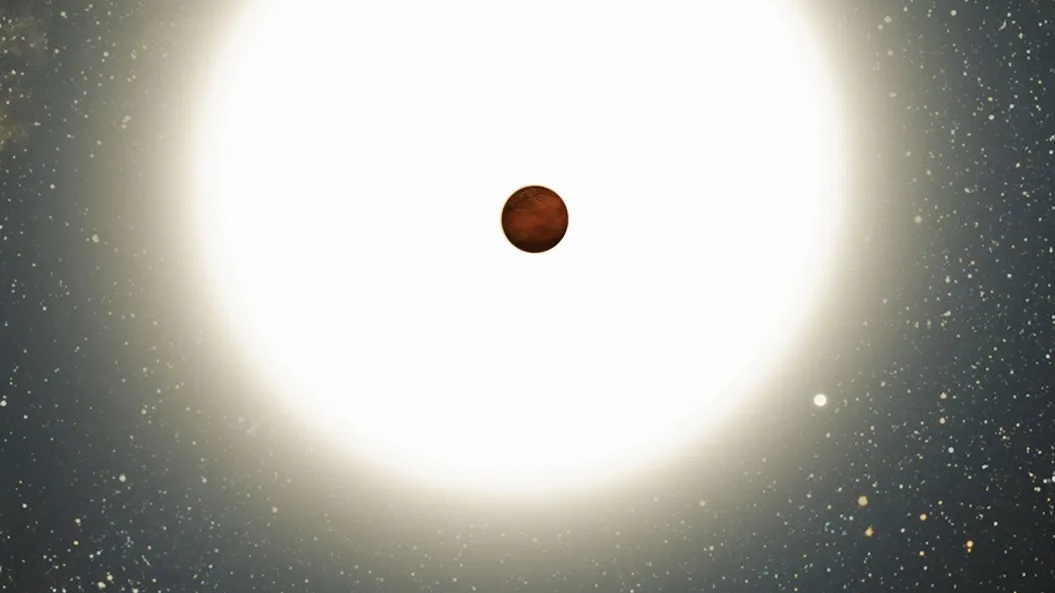

The planet, which is named TIC 393818343 b and resides about 300 light-years away from Earth, was confirmed by two networks of citizen scientists, the UNISTELLAR Network and NASA's Exoplanet Watch. The teams used their own telescopes to watch light from a nearby star dim. Such dimming is a tell-tale sign of an orbiting planet transiting between its star and our detectors on Earth. The first "transit" was detected by the UNISTELLAR group, which then predicted when the next one would occur and alerted NASA's Exoplanet Watch group to help watch the star during the predicted time, according to a NASA statement.

Sure enough, the networks detected two more transits, thus confirming the planet's existence and demonstrating the scientific impact of the burgeoning field of citizen science.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"I pinch myself every day when I recall that I have made a meaningful scientific contribution to astronomy by helping professional astronomers confirm and characterize a new exoplanet," Darren Rivett, a citizen scientist from Australia who contributed to the confirmation, said in the statement. "Researching as a citizen scientist is something I highly recommend to anyone who gazes at the night sky with awe and wonder."

TIC 393818343 b is possibly closer to its host star than Earth is to the sun. A "year" on the world currently lasts roughly 16 days, but that would shorten considerably should the world drift further inward and become a hot Jupiter, according to a study describing the exoplanet, which was published last month in The Astronomical Journal.

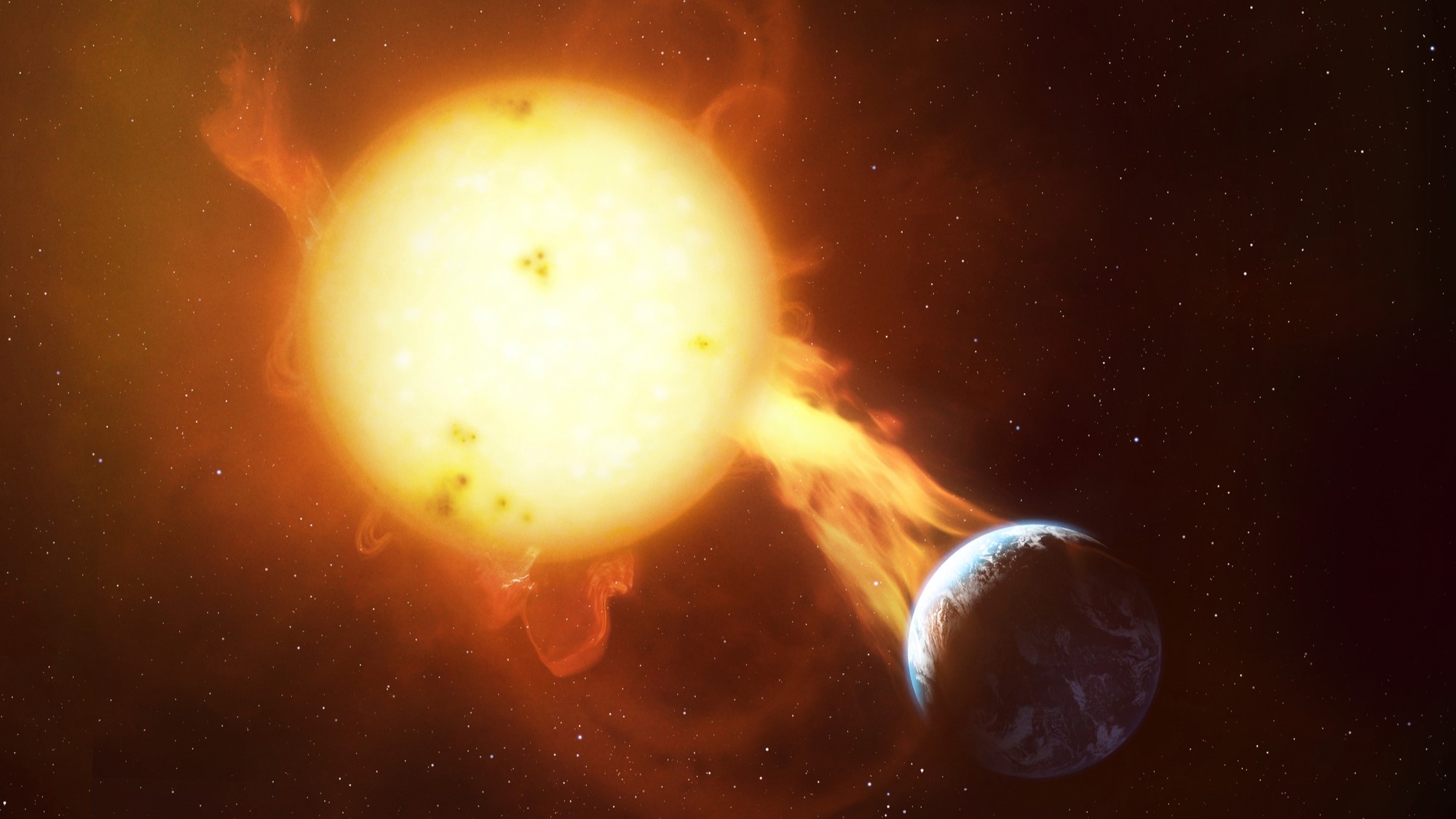

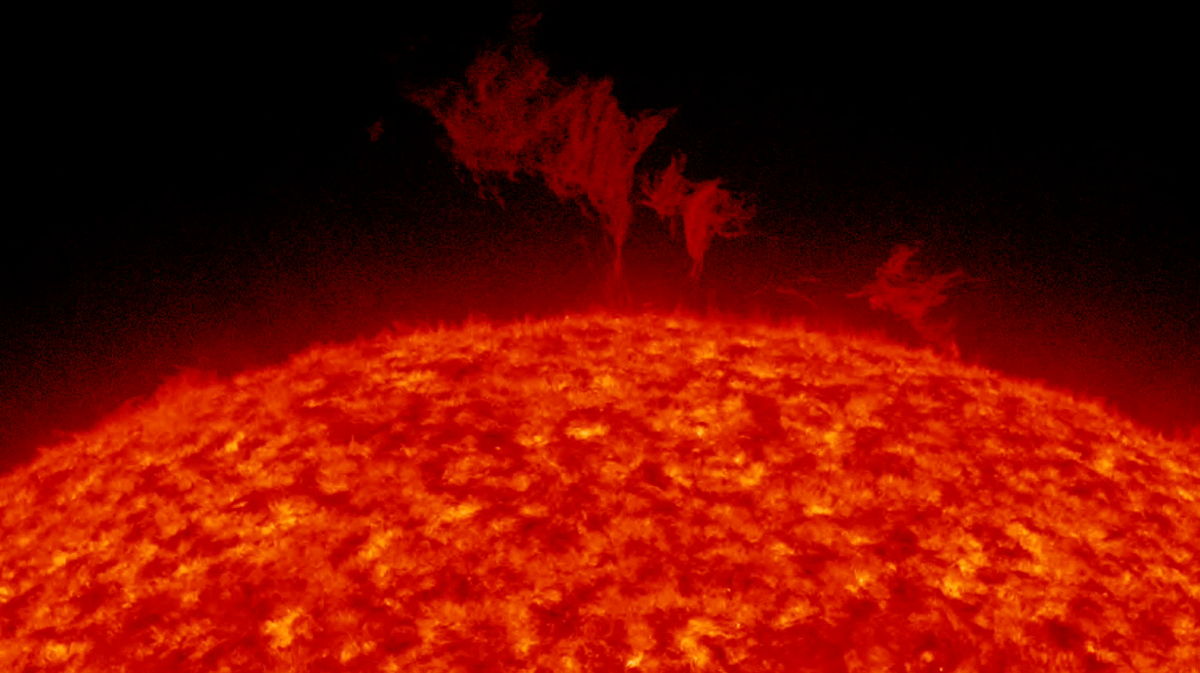

Astronomers say the migration itself may not occur before the sun-like host star runs out of fuel and balloons into a red giant, meaning the warm world would get scorched and become a hot Jupiter whether or not it drifts from its current orbit. Space telescopes may someday catch the "promotion" in action.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sharmila Kuthunur is a Seattle-based science journalist focusing on astronomy and space exploration. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She has earned a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social