Mysterious 'Sub-Neptunes' Are Probably Water Worlds

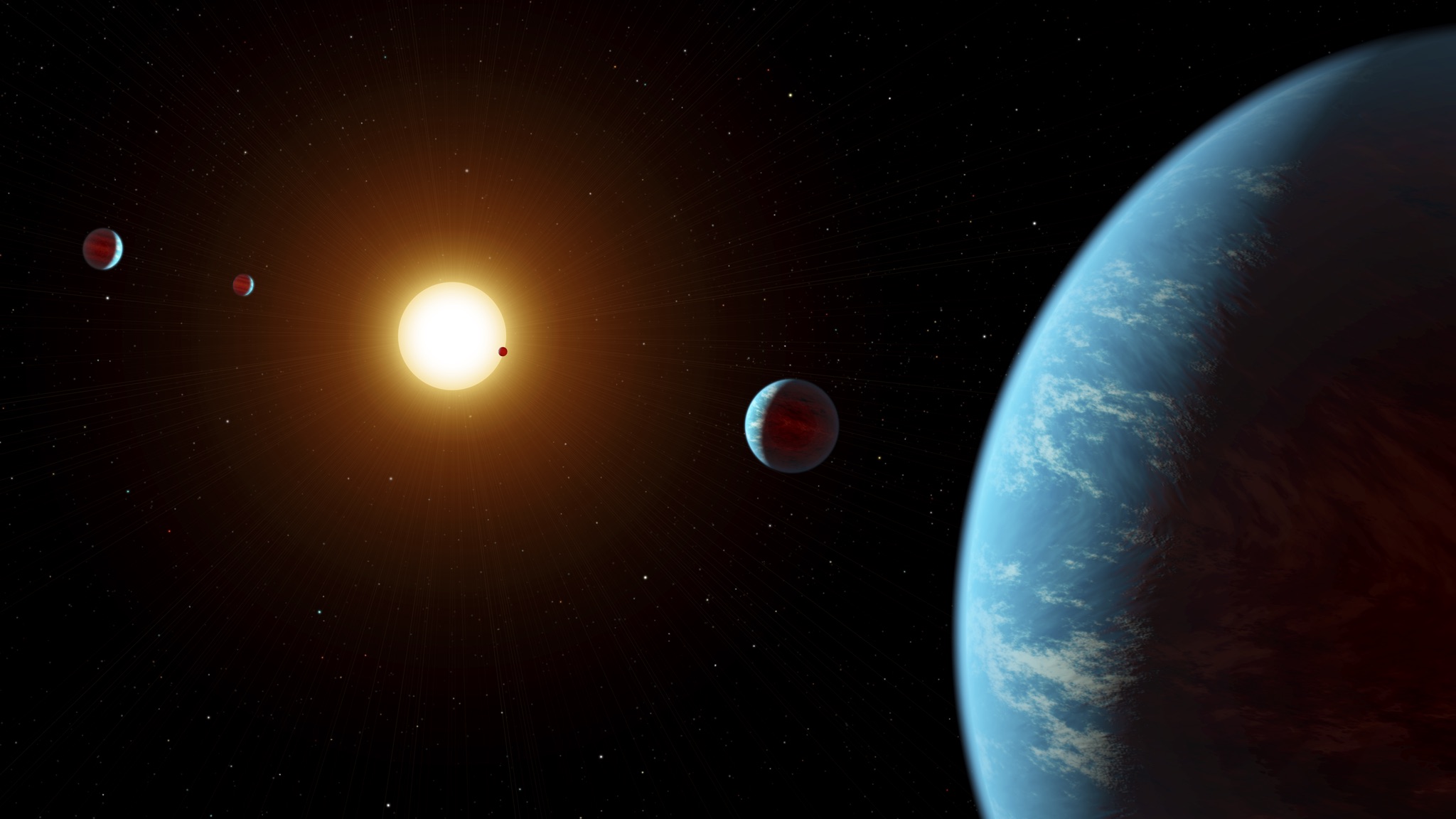

Most exoplanets between Earth and Neptune in size are probably all wet.

Water worlds that each possess thousands of times more water than Earth does may be more common than Earth-like rocky planets in the Milky Way galaxy, a new study finds.

Over the past 20 or so years, astronomers have confirmed the existence of thousands of exoplanets, or planets around other stars. NASA's recently deceased Kepler spacecraft discovered 2,702 confirmed exoplanets, and several thousand more "candidates" it found are awaiting confirmation.

Many exoplanets are quite unlike any planets in our solar system. For example, so-called super-Earths have diameters up to twice that of Earth, and "sub-Neptune" worlds are two to four times wider than Earth. (Neptune's diameter is about four times Earth's.)

Related: Images: The Strangest Alien Planets

Much remains hotly debated about sub-Neptunes, such as how they formed. Their compositions remain unknown, and understanding them could help shed light on these exoplanets' origins. Previous research suggested that sub-Neptunes were either gas dwarf planets with rocky cores surrounded by envelopes rich in hydrogen and helium, or water worlds with major amounts of liquid and frozen water in addition to rock and gas.

To investigate the makeup of sub-Neptunes, scientists ran computer simulations of planetary growth to see what scenarios might best explain the masses and diameters seen to date among exoplanets. Knowing the mass and diameter of a planet can help astronomers estimate its average density, and computer simulations of planetary growth can help reveal whether compositions of gas, rock, ice or water might best explain these densities.

The researchers found that sub-Neptunes are more likely to be water worlds than gas dwarfs. They suggested that each sub-Neptune is at least 25%, and possibly more than 50%,liquid or frozen water by mass. (In contrast, Earth is only 0.02% water by mass.)

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Our study suggests that there are on the order of 1,000 water worlds in just the Kepler confirmed and candidate planets," study lead author Li Zeng, a planetary scientist at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, told Space.com. "Statistically speaking, these water worlds may be more abundant than Earth-like rocky planets. Perhaps every typical sunlike star — a star of about one solar mass — has one or more of these water worlds."

The researchers divided exoplanets around sunlike stars into four main types:

- Rocky worlds up to twice Earth's diameter.

- Water worlds two to four times Earth's diameter that are each made up of more than 25% liquid or frozen water.

- Transitional planets four to 10 times Earth's diameter that are rich in ice and possess substantial gaseous envelopes.

- Gas giants more than 10 times Earth's diameter that are made up primarily of hydrogen and helium gas.

It remains a mystery why our solar system lacks planets between Earth and Neptune in size, and why the planetary systems that Kepler has seen often have more planets closer to their stars than our solar system does. Solving these puzzles might help shed light on how planetary systems typically form.

"Perhaps our solar system is less typical," Zeng said. Instead, planetary systems "with close-in rocky super-Earths and water-rich sub-Neptunes may be more common than our own solar system in our Milky Way galaxy."

The scientists detailed their findings online April 29 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

- Alien Planet Quiz: Are You an Exoplanet Expert?

- 7 Ways to Discover Alien Planets

- Latest News About Alien Planets

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us