What does space smell like?

The exotic chemistry of planetary and interstellar space produces a bouquet of unusual aromas — if only there were air in space in which to smell them.

Astronauts have described some unusual scents in space, which is not surprising considering the chemistry there is far different from that on Earth. So what does space smell like, and what are the cosmic sources of these odors?

Space is an airless vacuum, so technically, you can't smell anything in space — if you tried, you'd be dead. However, space is not a complete vacuum. It's full of all manner of molecules, some of which have their own strong odors when we smell them on Earth. Learning about what different parts of space might smell like is a really cool way to get a better understanding of cosmic chemistry.

Related: International Space Station has 'peculiar odor,' astronaut says

What do astronauts smell?

During the Apollo moon landings, the astronauts would often comment on a gunpowder-like smell once they had clambered back into the airlock, entered the confines of their lunar lander and removed their helmets. Similarly, after spacewalking, astronauts returning to the confines of the International Space Station report the smell of gunpowder, as well as ozone and burnt steak.

So what's going on? Where does the smell come from?

Scientists have two good theories. One is that, while an astronaut is on a spacewalk, single atoms of oxygen can adhere to their spacesuit, and when they reenter the airlock and repressurize, molecular oxygen — O2, or two atoms of oxygen — floods into the airlock and combines with the single oxygen atoms to form ozone, or O3. This would explain the sour, metallic smell.

So what about the other odors? There's probably something else going on. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), found in charred food like burnt toast and barbecued meat, also occur routinely in space. In fact, most interstellar carbon is locked up in PAHs. They're also plentiful in the solar system, so they can be picked easily up by astronauts and brought inside the space station or a space capsule — and they're probably the source of the burnt-meat smell that astronauts report.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Indeed, NASA treats the smells of space as more than just a curiosity. In 2008, the agency commissioned Steven Pearce — a chemist at Omega Ingredients, which specializes in fragrances and flavors — to reconstruct the smells of space for astronauts in training. After all, an astronaut needs to be able to distinguish between the smell of PAHs on their spacesuit and a dangerous chemical leak on board the space station.

Smelly comets

So we have an idea of what the space near Earth smells like. But what about further afield?

Other places in the universe also have unique odors — if only we could travel that far to smell them.

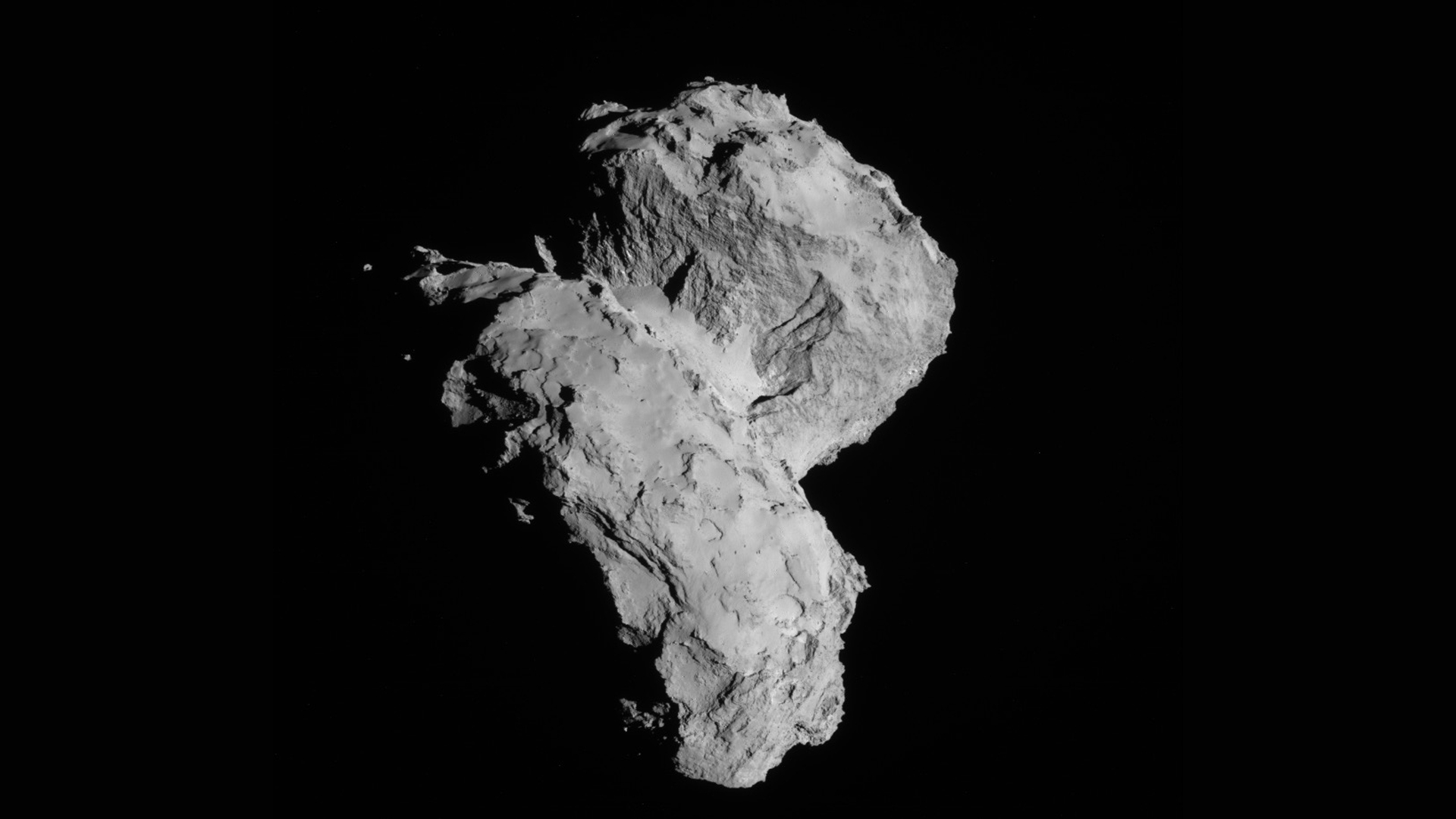

When the European Space Agency's Rosetta spacecraft encountered comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko in 2014, it detected a rich variety of molecules in the comet's coma, the gaseous halo that surrounds the comet's solid nucleus. Among these molecules were hydrogen sulfide, which gives rotting eggs their unsavory stench; ammonia, which is reminiscent of the repulsive smell of urine; hydrogen cyanide, which, despite its famously toxic nature, has a more appealing almond-like smell; sweet-smelling carbon disulfide; and the pickled aroma of formaldehyde.

You'd likely turn your nose up at this combination of odors. But if there were any smell, it would likely be pretty weak, as the vast majority of a comet's coma is water vapor and carbon dioxide.

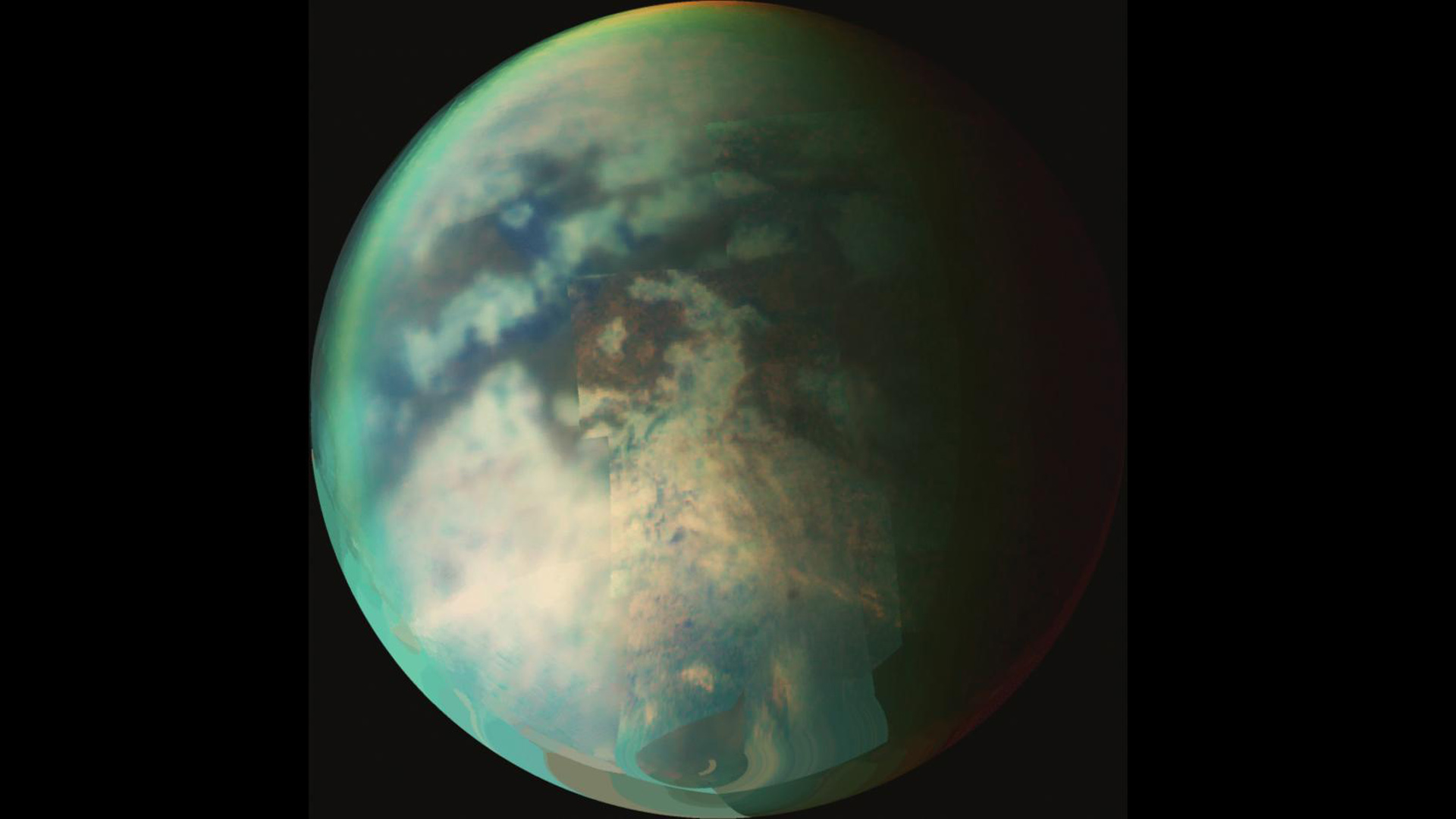

The gasoline moon

One place where there is an atmosphere to hold a scent is Saturn's largest moon, Titan. The atmosphere doesn't really help us smell anything, though. There's no oxygen, and it's chilly — minus 292 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 179.6 degrees Celsius) — so it's not really an option to take off our spacesuit helmet and breathe in deeply. If we could, however, we would find that Titan reeks of gasoline.

Perhaps we shouldn't be surprised. After all, gasoline, or petrol, is made from crude oil rich in hydrocarbons, which are molecules formed of atoms of hydrogen and carbon, such as methane and ethane. Titan's atmosphere contains a dense smog of hydrocarbons, and on the moon's surface, liquid hydrocarbons form oily lakes and rivers. But methane, which is the dominant hydrocarbon on Titan, doesn't smell of anything. So what creates the moon's stench?

NASA's Cassini spacecraft identified an unknown chemical in Titan's hazy atmosphere that NASA laboratory experiments on Earth determined was a molecule containing nitrogen, methane and benzene and belonging to a family of molecules called polycyclic aromatic nitrogen heterocycles (PANHs). In particular, it's the benzene in the PANHs that gives Titan its petroleum stench, since benzene is also found naturally in gasoline.

A boozy gas cloud

So the solar system is a pretty pungent place, but what about the rest of the universe?

Sagittarius B2, a giant interstellar molecular cloud of star-forming gas and dust less than 400 light-years from the center of the Milky Way, has all kinds of aromatic chemistry going on. For one thing, it contains lots of alcohol, including vinyl alcohol, methanol and ethanol, the kind of alcohol in beer.

In 2009, astronomers also detected the molecule ethyl formate in Sagittarius B2. Ethyl formate is the chemical that gives raspberries and rum their sweet fragrances, so even if the center of our galaxy smells like a brewery, at least it will be a pleasant one.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Keith Cooper is a freelance science journalist and editor in the United Kingdom, and has a degree in physics and astrophysics from the University of Manchester. He's the author of "The Contact Paradox: Challenging Our Assumptions in the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence" (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2020) and has written articles on astronomy, space, physics and astrobiology for a multitude of magazines and websites.