The Local Bubble: How our solar system got caught up in a cosmic crime scene

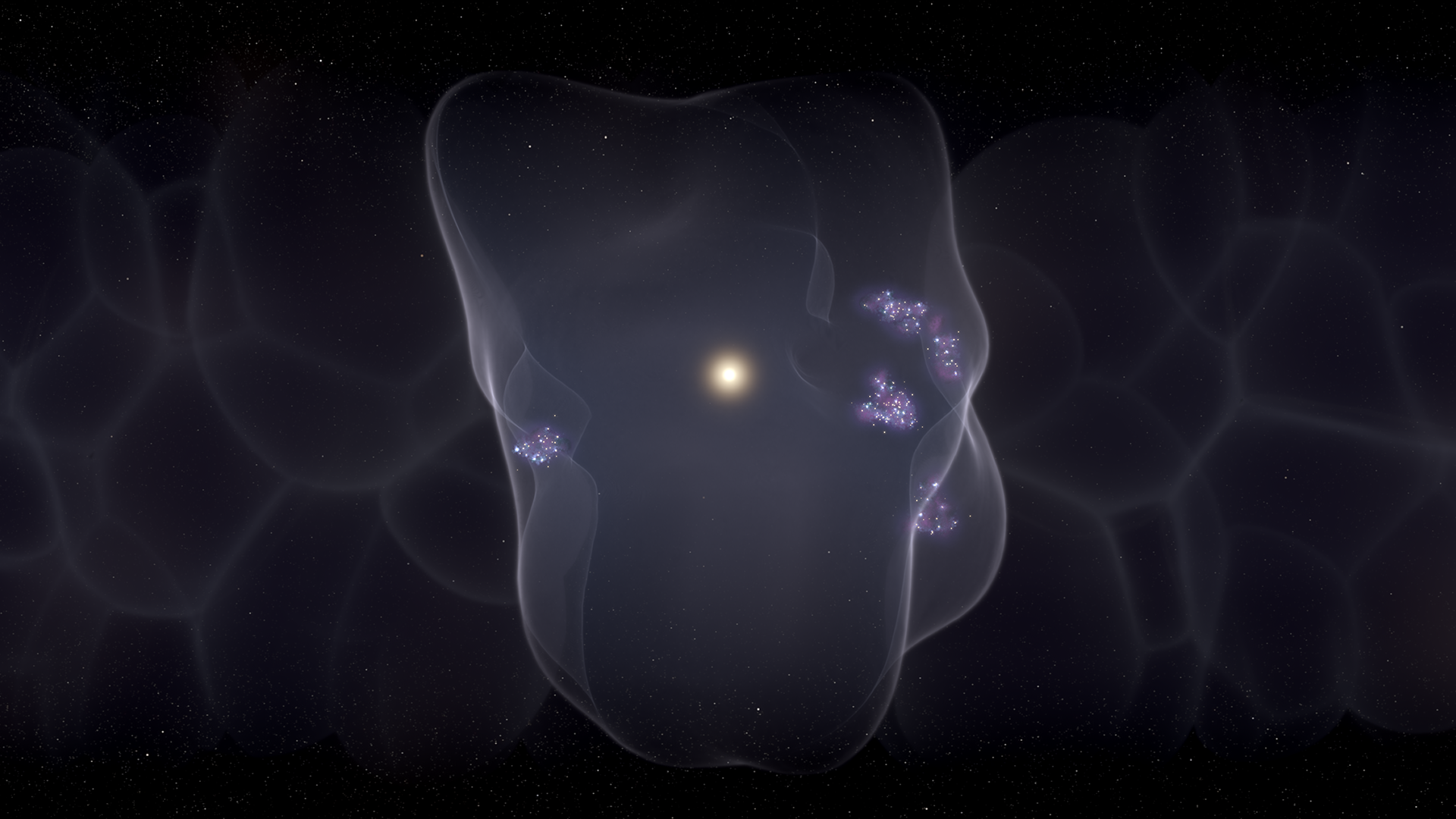

Our solar system resides inside a vast cavity, now known as the Local Bubble, which is about 1,000 light-years across.

The Local Bubble is a region of surprisingly low-density gas that surrounds our solar system and other nearby regions of our galaxy — and it has a violent history. Here's how our solar system ended up in the middle of a cosmic crime scene.

On Jan. 12, 2003, NASA launched the Cosmic Hot Interstellar Plasma Spectrometer (CHIPS). Its mission was to study the nearby interstellar medium (ISM), which is the superheated and incredibly thin gas that stretches between the stars. CHIPS was designed to measure the ultraviolet radiation (UV) coming from the ISM and build a map.

But it didn't find much at all. The lack of significant UV radiation indicated that our nearby region of the Milky Way galaxy was weirdly empty. This result added to a couple decades' worth of evidence that something strange was going on with the ISM.

More research revealed that our solar system resides inside a vast cavity, now known as the Local Bubble, which is about 1,000 light-years across. The interstellar medium within the Local Bubble is less than one-tenth the average density of the Milky Way, and it's surrounded by a relatively denser shell. That shell contains many associations of large stars and star-forming molecular clouds.

The sun was not born within the Local Bubble; it entered it only about 5 million years ago. It's like the solar system walked onto the scene of a violent crime. So what happened?

Related: Astronomers make 1st-ever 3D map of Local Bubble's magnetic fields

Making the bubble

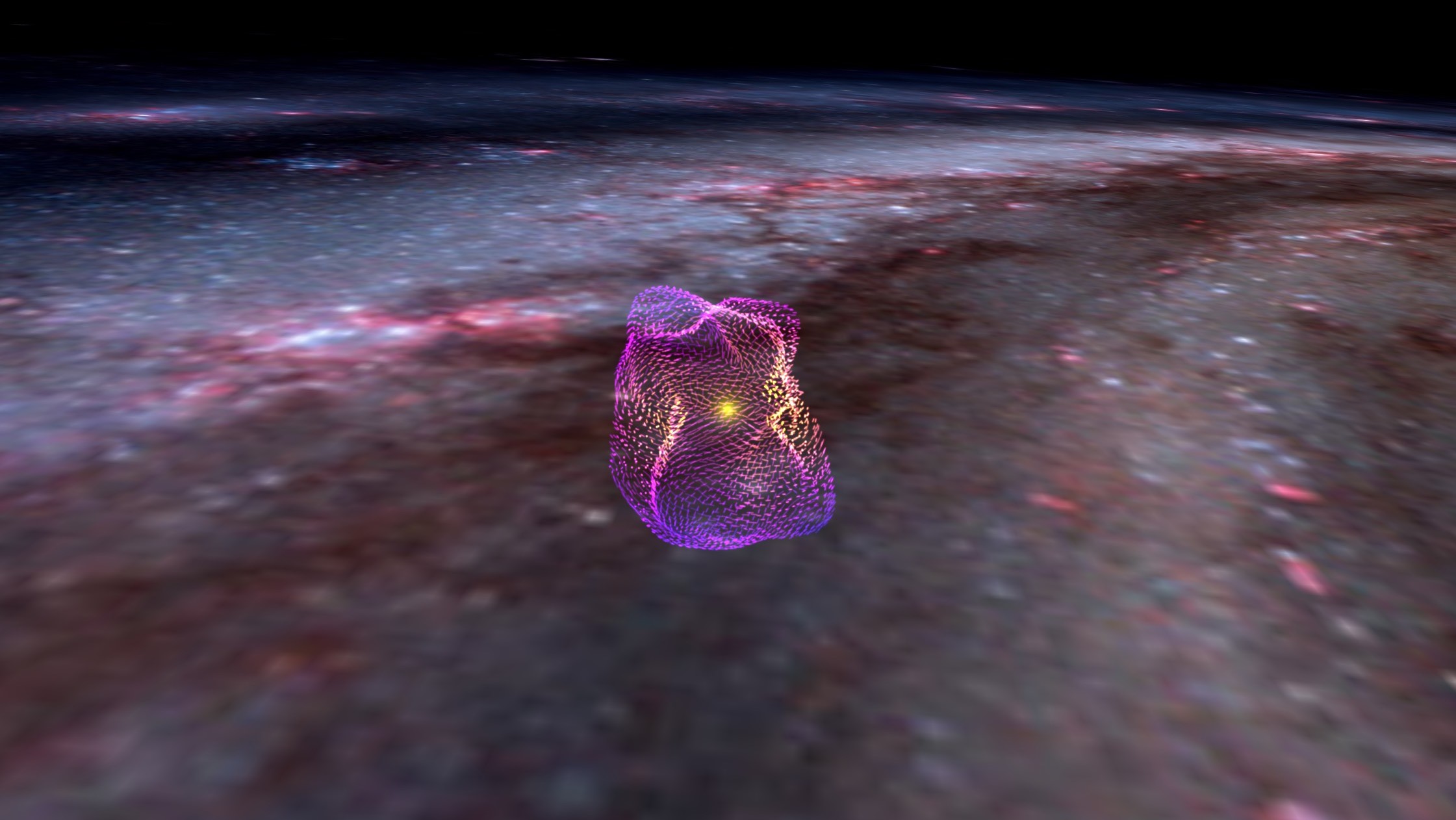

Astronomers suspect that the Local Bubble formed about 14 million years ago, when up to a 1,000 supernovas went off at about the same time.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

These kinds of clustered supernova events aren't unheard of in the galaxy. Stars are almost always born in clumps, with a single molecular cloud producing hundreds, or even thousands, of stars in a single go. Most of these stars are small red dwarfs, some are midsize stars like the sun, and the remaining ones are huge. Those huge stars are on a track to end their lives in a supernova blast, and because they were born at about the same time, they're likely to explode at roughly the same time, too.

When a single supernova goes off, it can carve out a cavity around it, pushing away the ISM with the force of its shock wave. Plus, near the end of its life, it blasts out intense bursts of high-energy radiation, which contributes to the excavation project. Combining hundreds, or even up to a thousand, such supernovas can provide the energies needed to form something like the Local Bubble.

The material swept up by the supernovas during the formation of the Local Bubble currently sits at its edge, and that high-density environment serves as the current site of star formation in the local vicinity of the solar system. All newborn stars and star-forming regions are found within the Local Bubble's shell.

Meeting the bubble

The sun did not form along with the stars that would eventually die and carve out the Local Bubble; it entered the bubble's region only about 5 million years ago. Astronomers can determine that through a combination of the sun's velocity within the Milky Way and the presence of radioactive elements found on Earth.

Earth formed about 4.5 billion years ago with a substantial complement of radioactive elements and isotopes. Some of those, like iron-60, have a half-life of only a few million years, which means they should have decayed a long time ago. Yet they can still be found in ancient seabeds, meaning they must have been replenished more recently.

The best explanation is that about 5 million years ago, the solar system passed through the shell surrounding the Local Bubble. Because that shell hosts active star formation, it is also home to a disproportionate number of recent supernovas, including their radioactive byproducts. Those radioactive elements filtered their way into the solar system and sprinkled themselves onto Earth, explaining the recent contamination.

The solar system will continue traveling through the Local Bubble for another 10 million to 20 million years. But over time, the bubble will disperse, and its shell will fragment the rest of the ISM flowing in to fill the void. Millions of years from now, you would never know the drama of what happened there.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Paul M. Sutter is an astrophysicist at SUNY Stony Brook and the Flatiron Institute in New York City. Paul received his PhD in Physics from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 2011, and spent three years at the Paris Institute of Astrophysics, followed by a research fellowship in Trieste, Italy, His research focuses on many diverse topics, from the emptiest regions of the universe to the earliest moments of the Big Bang to the hunt for the first stars. As an "Agent to the Stars," Paul has passionately engaged the public in science outreach for several years. He is the host of the popular "Ask a Spaceman!" podcast, author of "Your Place in the Universe" and "How to Die in Space" and he frequently appears on TV — including on The Weather Channel, for which he serves as Official Space Specialist.

-

Unclear Engineer Trying to think about the numbers provided in the article:Reply

14 million years ago, about 1,000 large stars went supernova more or less together, and blasted out a void that is now 1,000 light-years in diameter - with a lot of star formation still going on at its boarder with unperturbed galactic material.

Our Earth entered it about 5 million years ago, and is expected to exit the void in another 10 to 20 million years.

So, Earth's velocity with respect to the void is something like 1,000 light years/ (~20 million years) = 0.00005c.

Assuming the 1,000 supernovas were in the center of the void, and Earth is still maybe half-way to the center, that puts Earth about 250 light years + 14 million years x 0.00005c = ~950 light-years from 1,000 supernovas about 14 million years ago.

I am wondering if the high frequency EM radiation (UV to gamma rays) from that should have had any effects on Earth's climate, at that distance.

I think it was a good thing that Earth wasn't a lot closer.