Book excerpt: 'What Stars Are Made Of' (Harvard University Press, 2020)

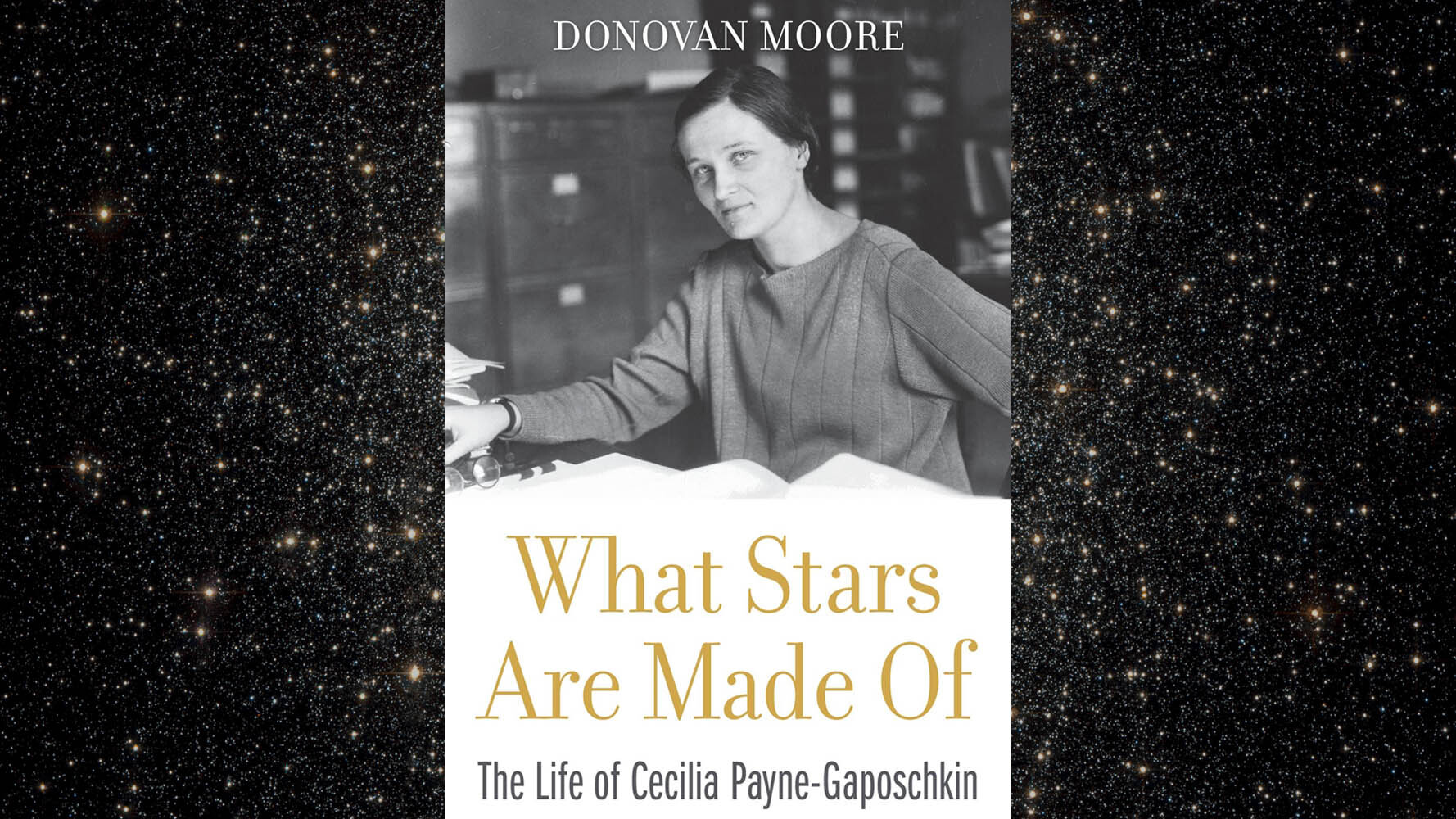

In his new book, "What Stars Are Made Of: The Life of Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin" (Harvard University Press, 2020), author Donovan Moore tells the story of a young British scientist at the forefront of astrophysics.

In 1925, Cecilia Payne, later known as Payne-Gaposchkin, published a thesis overturning the then-established wisdom that the sun is made of the same basic ingredients as Earth's crust. Instead, Payne had realized, the sun appeared to be primarily hydrogen. She was pushed to muddy her findings but was eventually proved correct.

"What Stars Are Made Of" focuses on her education and early research, including when she struggled to fit the pieces of the composition puzzle together using her predecessors' work on a collection of thousands of glass plates.

Related: Read an interview with Donovan Moore here.

Chapter 15

"I had left the world of dreams and stepped into reality." So wrote Cecilia when she described her transition from the Old World to the New. "Abstract study was a thing of the past; now I was moving among the stars."

***

Two years into the job, Harvard College Observatory director Harlow Shapley must have beamed when he saw Cecilia walk through the door. He may not have envisioned forming a "Shapley's harem," but he certainly viewed Cecilia as a worthy member of his team of new "computers" to carry on the Pickering legacy. He initially gave her the courtesy of asking what she wanted to work on. But before she could answer, he pressed on, saying that he thought she would be perfect for continuing Henrietta Leavitt's work on standard photometry. Cecilia had other ideas. "I was in a different position from the other girls," as she described it. "They were employed to do a job, but I was on a Fellowship, so I was independent and had no obligations."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

She was correct. Technically, she was not an employee, so Shapley couldn't tell her what to do. She was a smart, hard-working young woman, living on a subsistence income with an office in the observatory — the very definition of an observatory computer — but she was not under his thumb. That realization gave Shapley pause. He then asked, delicately, what exactly she did want to do. Cecilia responded as she always did — directly, to the point. She said she wished to do what E.A. Milne had suggested: test Meghnad Saha's theory of stellar composition.

The observatory's million photographs held a vast store house of scientific data. But without interpretation, it was as if a treasure trove were held under lock and key. What Cecilia was proposing was a way to unlock it: apply her Cavendish Lab knowledge of physical chemistry to the Harvard College Observatory's collection of stellar spectra. She wanted to bring astrophysics to Harvard. Shapley may have initially misjudged Cecilia, but he did recognize the value of combining the Cav Lab with the HCO. As Cecilia described it in an interview years later, Shapley told her, "'All right, go ahead. There are the plate stacks.' So I was left just to sink or swim. There wasn't anybody to help because it was a subject nobody knew about."

***

Cecilia banished thoughts of home by going after the collection of stellar plates with the same intensity she showed for the regular library. Ironically, her early botany training proved valuable. William Bateson and Agnes Arber had shown her the importance of the systematic classification of plants. Working as if she were a stellar botanist, Cecilia applied the same principle to the plates, viewing her task as "ranging over the astronomical photographs, collecting and classifying the celestial flora."

There were hundreds of thousands of stellar photographs; analyzing them would be hopeless without a systematic approach. Cecilia created a set of log books, with her name carefully recorded on the flyleaf, each one a comprehensive recording of the star she was studying, crafted in the same careful handwriting she had used to correspond with Shapley. "A look at her log books from the photographic plate stacks shows a person who hit the ground running as she searched the cumbersome and voluminous archive," her daughter, Katherine, remarked.

The work of cataloging that "voluminous archive" had already been largely done. Pickering's computers had swept the sky clean by the time Cecilia took over Henrietta's desk. Over more than twenty-five years, Annie Jump Cannon alone had classified 350,000 spectra. But that's all Annie did. "She had amazing visual recall, but it was not based on reasoning," Cecilia noted. "She did not think about the spectra as she classified them — she simply recognized them." It was as if Annie had built a massive library and stocked it with an enormous number of books but then never read a single one of them. Cecilia could not help but "wonder how anyone who had worked with stellar spectra for so long could have refrained from drawing any conclusions from them."

There were two reasons. First of all, it was not Annie's job to draw conclusions. She had been hired to use her eyes. But more important, Annie did not have the tools for exploration that Cecilia had. She had not been trained in the rigorous environment of the Cavendish Lab. She had not learned from Niels Bohr about how electrons orbit a nucleus. She had not had a determination to understand honed and hardened by a Nobel laureate singling her out as the only woman in the physics class.

***

This hunt was on: Cambridge training meets Harvard data. Cecilia never described her feelings at that moment, but she had to know that she had a shot at a major discovery. "I saw in the stars a chance to observe phenomena beyond terrestrial scope. Nothing seemed impossible in those early days; we were going to understand everything tomorrow."

Cecilia's extraordinary level of energy was now finally unleashed. At Cambridge, if she had wanted to study after 11 p.m., it had to be done in bed by candlelight. At Harvard, she could come and go as she pleased, work all night if she wanted to. "When she set herself a task, she was indefatigable," according to her daughter, Katherine. "Her powers of concentration were so great that she could work for hours without stopping."

At first it was too much. Cecilia was trained in modern atomic physics, but when she began examining Annie Cannon's quarter million observations, she found the spectrum of starlight on any given plate to be little more than "tiny parallel smears." How was she to apply atomic theory to a smear?

Despair comes in different forms to different people. To a scientist, it comes as bewilderment. Months and months of time; packs and packs of cigarettes. No progress. Cecilia despaired. The tiny smears simply would not reveal their secrets. Shapley watched and waited. For a man whose career depended on results, it must have been excruciating. He had to have had moments of doubt about the wisdom of offering precious plate access to this admittedly hard-working young woman with an increasingly edgy personality.

Late one night it bubbled over. She could hear his footsteps as he jogged across the courtyard from his residence to the Brick Building. He approached Cecilia, sitting as usual at Henrietta's desk, plates spread out under the lamplight. "Don't you think you should publish something?" he asked. "To give some evidence of the work you're doing."

"No!" she snapped. "I should regard it as a confession of failure." Shapley backed away.

Excerpt adapted from What Stars Are Made Of: The Life of Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin by Donovan Moore, published by Harvard University Press. Copyright © 2020 by Donovan Moore. Used by permission. All rights reserved. You can buy "What Stars Are Made Of" on Amazon or Bookshop.org.

- How to tell star types apart (infographic)

- What's inside the sun? A star tour from the inside out

- Harvard's 'computers': The women who measured the stars

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'All About Space' 'How it Works' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.