The Moon on Earth: Where Are NASA's Apollo Lunar Rocks Now?

Like any travelers, the 12 astronauts who have walked on the moon were careful to bring back souvenirs from their journeys. In their case it was moon rocks, and lots of them.

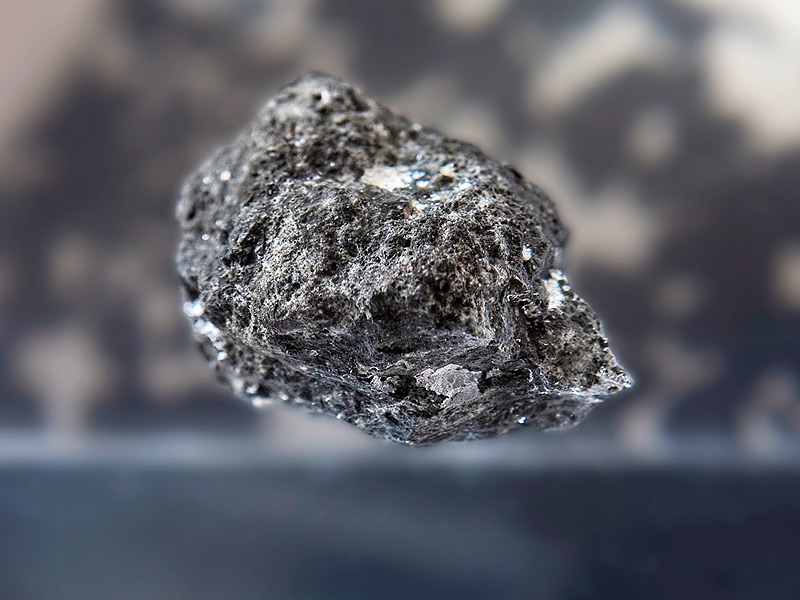

All told, the six Apollo missions collected 2,196 samples, which weigh 842 lbs. (382 kilograms) under Earth's gravity — nearly as much as a horse. But although those samples were collected over just a few days scattered across four years, they've racked up decades of adventures on Earth.

NASA still holds onto about 85% of the moon rocks collected by astronauts during the Apollo program. The rest has met a variety of fates. "Some of it's been used for science, some of it's been used for museums, and some of it's been used and sent back to us," Ryan Zeigler, Apollo sample curator and manager of NASA's Astromaterials Acquisition and Curation Office, told Space.com in March.

Related: Apollo 11 at 50: A Complete Guide to the Historic Moon Landing

The Apollo moon rocks aren't the only pieces of the moon on Earth, but they are unique in having been collected by astronauts on the lunar surface. Three robotic missions conducted by the Soviet Union brought back their own samples, but much less — just 0.7 pounds (0.3 kilograms).

There's also lunar material on Earth that isn't referred to as moon rocks: Geologists have also identified plenty of meteorites that originated on the moon, but the scientific value of these samples is trickier because there's no way to trace them back to a particular spot on the lunar surface.

But the Apollo collection — those 2,196 samples, which NASA has broken into 140,000 pieces — have perhaps the most poignant aura about them. Six of those samples are even more special, since they have never been unpacked from when they were sealed on the moon.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Months after the Apollo 11 astronauts splashed down on Earth from conducting the first-ever moon walks, President Richard Nixon arranged for U.S. states and territories and 135 countries to each receive a few tiny lunar samples, accompanied by the flag that had flown on the mission, as diplomatic gifts. (Notably, the Soviet Union, which lost the space race as the first U.S. astronaut set foot on the moon, was not on the list.)

Nixon completed a similar gifting process with fragments of a rock collected during the final moon landing astronauts conducted, the Apollo 17 mission in 1972. (This time, the Soviets made the cut.) Both rounds of samples have met scattered fates: some treasured and put on display, some lost, some tucked away in storage.

They are the only moon rocks not legally the property of the U.S. government; the rest of the collection remains with NASA, based at a laboratory at the Johnson Space Center in Houston. That facility is home to not just the Apollo rocks, but also thousands of samples from meteorites, comets, cosmic dust and the solar wind.

A portion of those samples at any given time are out on loan to museums for public display and scientists for research projects. Occasionally, the processes involved in that research destroys the rocks, but for the most part they cycle in and out of labs and storage facilities.

For Zeigler, whose job involves overseeing that process, all of the astromaterial samples are something special, with much longer life spans than measurements beamed back to Earth from distant spacecraft.

"When you bring samples back, any samples, you now get to do decades of follow-up study because you have the rock," Zeigler told Space.com December. "Twenty years from now, when you have better instruments, you can do better work."

- Catch These Events Celebrating Apollo 11 Moon Landing's 50th Anniversary

- NASA's Historic Apollo 11 Moon Landing in Pictures

- Reading Apollo 11: The Best New Books About the US Moon Landings

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.