Recently, a friend of mine asked when we might be able to see a comet. He was surprised when I said there are several visible right now.

Indeed, you can find a list of upcoming visible comets on this useful site compiled by Japanese comet enthusiast Seiichi Yoshida. The site provides information on comets that are currently visible as well as comets that will be visible each month for the next five years. For this month, Yoshida lists four observable comets.

But none gets brighter than magnitude +12 (lower magnitudes are brighter), and the comets are visible only under dark, clear skies, using moderately large telescopes. Indeed, the vast majority of periodic comets — comets whose orbits are well known and have been observed more than once — fall into this category. These comets quietly come and go and are known only to enthusiastic amateur astronomers who make a concerted effort to hunt them down with good binoculars or telescopes. Generally, they are unimpressive to the eye, usually appearing as nothing more than faint fuzzballs, even in large telescopes.

Related: Living on a Comet: 'Dirty Snowball' Facts Explained (Infographic)

Of course, when my friend asked his question, I knew exactly what he was alluding to: He wanted to know when we might see a stupendously bright and/or fantastically structured comet, perhaps one that would develop a tail stretching a quarter of the way or more across the sky. Unfortunately, such objects give no advance notice as to when they will appear. But with some confidence, I can state that at least one of these comets is heading toward the inner solar system even as I type these words.

But whether it will appear three weeks, three months or three years from now is unknown.

So what are our chances of seeing such a celestial showpiece? More on that in a moment, but first, let's talk about what needs to happen to produce a bright comet.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Recipe for a bright comet

The unpredictability of a passing comet's appearance and brightness is no surprise to those who study these enigmatic objects. What we see depends on many variables — the comet's orbit; the relative locations of the comet, Earth and the sun; and the size and composition of that icy clumping of solar system rubble that forms the comet's nucleus.

The nucleus's dusty, rocky material and frozen gases are similar to the composition of Saturn's rings. This part of a comet, usually only a few miles across, is gradually warmed by the sun's heat, and expels gas and dust into space, often in distinct jets. But such emissions from the nucleus are often nonuniform. To predict comets' activity, astronomers have developed general formulas and models for comet brightness based on the observed behavior of many comets going back to the late 19th century. Usually, a comet's activity increases rapidly as it draws closer to the sun; the brightness typically varies (roughly) as the inverse fourth power of its solar distance.

Put another way, as a comet's distance from the sun is halved, its brightness increases by a factor of 16, or three magnitudes.

But comets can be capricious and, like people, have their individual quirks. The physical appearances and behaviors of comets are as varied as the appearances and behaviors of people; no two are alike.

Perhaps just as important, if not more important, than a comet's approach to the sun is the comet's distance from Earth. An average-size comet can appear stupendously large and bright if it passes very close to Earth. An excellent case in point is Comet Hyakutake, which made a close approach to our planet in March 1996, coming to within 9.5 million miles (15.3 million kilometers) of Earth. It reached zero magnitude and was accompanied by a 100-degree tail (stretching across more than half the sky). But if Hyakutake had approached no closer than Comet Hale-Bopp (122 million miles, or 196 million km), it would have appeared no brighter than magnitude +6, which would have placed it right on the verge of naked-eye visibility in a non-light-polluted sky.

Conversely, if Hale-Bopp — which was at its best in March 1997 — had passed as closely as Hyakutake, it would have blazed at magnitude -6, three times brighter than Venus, with a tail stretching across the entire sky!

The tail wags the comet

Speaking of tails, that particular appendage might be the most important factor in determining whether a comet can be branded as a truly prominent object. I still remember a cold Saturday evening in January 1986, dubbed "Halley's Comet Night" by then-New York Mayor Ed Koch. In all five boroughs, Koch had arranged for designated locations to temporarily extinguish their normally bright lights to give his constituents the opportunity to get a better view of this famous comet, which was low in the western evening sky. At Jones Beach on Long Island, about 40,000 people gathered to catch a glimpse of Halley. Local astronomy clubs set up telescopes for the general public. I brought my 10-inch Dobsonian telescope and used low power to provide a nice wide-field view. The line of people patiently waiting for a look was incredibly long, but after peering through the eyepiece and seeing only a small, nebulous patch with a starlike center, virtually every person asked the same question: "Where's the tail?" One nonplussed woman seemed to speak for everyone when she exclaimed (a bit like Lucy from the Peanuts comic strip), "What good is a comet if it doesn't have a tail?"

Indeed, a comet can get bright yet lack a tail. In May 1983, Comet IRAS-Araki-Alcock passed within 2.9 million miles (4.7 million km) of Earth and, within a week, sped across the sky, resembling nothing more than a fuzzy ball of light about the size of the moon. Then, there was Comet Holmes in October 2007, which unexpectedly flared in less than two days from magnitude +17 to +2.5. To the unaided eye, it appeared more like a nova, a moderately bright yellow star, in the constellation Perseus.

So, it appears that the tail is what determines how impressive a comet will look to the average person.

Related: Amazing Comet Photos by Stargazers

Cast of comets

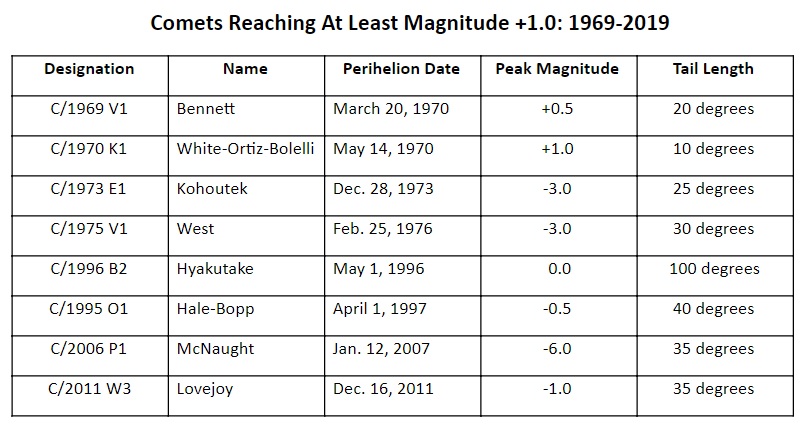

Now back to the original question: When might we see another bright comet? In the table below, I have listed the brightest comets that have appeared over the past 50 years. There are eight on the list, making an average of one about every 6.25 years. Of course, they didn't appear precisely at 6.25-year intervals. In 1970, for instance, Comet Bennett — which put on a spectacular show in late March and early April — was followed in May by Comet White-Ortiz-Bolelli, a rare sungrazing comet. In contrast, Comet Lovejoy, another sungrazer, brightened the Christmastime skies of 2011. And nearly eight years later, we're still waiting for another bright comet to appear.

There are disclaimers regarding a few of these bright comets. Those of a certain age may remember Kohoutek as being ballyhooed as potentially the "comet of the century." Though it briefly got very bright as it passed perihelion, its closest approach to the sun, it was then visible only to the astronauts on board the Skylab space station. For people on the ground, however, the comet was quite dim both as it approached the sun and as it receded into space. Many referred to Comet Kohoutek as the "flop of the century."

Comets White-Ortiz-Bolelli, McNaught and Lovejoy were at their best chiefly for people in the Southern Hemisphere; there have been no really fine and bright comets visible from the Northern Hemisphere since Hale-Bopp in 1997, — 22 years ago. "There can be seemingly long stretches without any spectacular comets being seen, but that by no means necessarily implies absolutely none occurred," noted comet observer John E. Bortle. "Random selection in apparition circumstances can indeed prove to be very cruel at times."

Sometimes, that's just the way it is with comets.

Final evaluation

But the bottom line is that, based on the law of averages, we are overdue for another bright comet. Hopefully, we won't have to wait too much longer to see one.

And when another bright comet does finally come, you'll get all the details on how to best observe it, right here at Space.com. Stay tuned!

- Photos: Spectacular Comet Views from Earth and Space

- Photos of Halley's Comet Through History

- Stargazers Capture Amazing Photos of Comet 21P

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for Verizon FiOS1 News in New York's lower Hudson Valley. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.