Why can't we put a space station on the moon?

This article was originally published at The Conversation as part of the Curious Kids series. The publication contributed the article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insight.

Ian Whittaker, Senior Lecturer in Physics, Nottingham Trent University

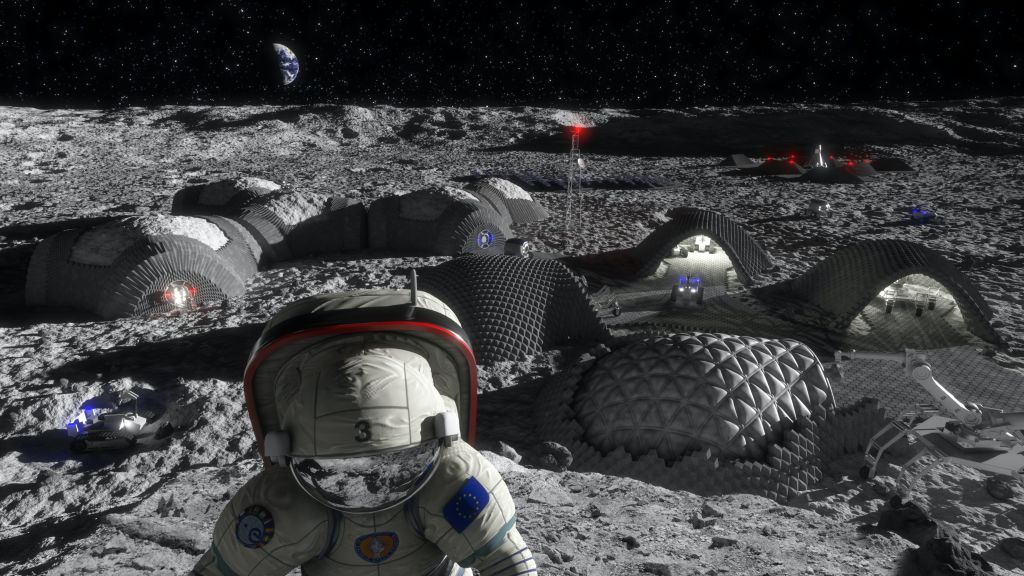

A space station on the moon could be very useful. It would provide future space missions with a stopping point between leaving the Earth and reaching further into the solar system or even the Milky Way.

One reason we haven’t built a space station on the moon is that we don’t send people there very often. We have only managed to put astronauts on the moon six times so far. These moon landings took place in a three-year period between 1969 and 1972 and were part of a series of space missions called the Apollo missions.

The type of rocket used to get the astronauts to the moon was an extremely powerful one called a Saturn V, which is no longer produced. This means that, at the moment, we do not have a rocket powerful enough to get people to the moon – let alone build a space station there.

Related: NASA's Gateway moon-orbiting space station explained in pictures

We are starting to build powerful rockets again. Space exploration company SpaceX is creating newer and bigger rockets which are capable of taking the weight of astronauts to the moon. NASA is also planning new missions to take astronauts to the moon.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

However, there is a big difference between a short trip and building a space station on the moon, which is extremely difficult. One way to do it would be to build it in pieces on Earth, take the pieces to the moon and assemble them there. This would be like how the International Space Station was built: pieces were taken into space and then put together by astronauts aboard the space shuttle.

However, the International Space Station is only 250 miles (400 kilometers) from the surface of Earth. The moon is 230,000 miles (384,000 km). Each trip to the moon would take about three days and would require incredible amounts of fuel, potentially adding to climate problems on Earth.

A much better idea would be to build as much of the base as possible from materials found on the moon. Lunar concrete is being tested on Earth as a possible building material.

On Earth you would make concrete from gravel or sand, cement and water. We have none of those things on the moon, but what we do have is lunar dust and sulphur. These can be melted and mixed together. Once this mixture cools, it produces a solid material that is stronger than many materials we use on Earth.

Food and power

We also need to think about what astronauts staying at the space station would need. The most important things would be a food supply and electricity to power equipment, food production and breathable air.

Scientists have been working on how to grow food in space. On board the International Space Station, astronauts are carrying out experiments to try to grow vegetables using soil pillows. Another option would be to grow plants using hydroponics, which means that the plants grow in water, not soil.

Getting power on the moon would be more complicated. The best way would be to use solar energy from the sun. However, the moon rotates every 28 days. This means that a space station in a fixed position on the moon would be in the sun for 14 days and then darkness for 14 days – and without light, solar-powered equipment wouldn’t work without a big improvement in battery storage.

One way to get round this problem would be to build the space station at either the north or south pole of the moon, and raise the solar panels above the surface. The panels would get constant sunlight as they can rotate and not be blocked by the planet at all.

Alternatively, we might not even need a base on the surface of the moon at all. Instead, NASA is planning to build a satellite to orbit the moon. Rockets launching from the lunar surface use more fuel to escape the moon’s gravity, but this would not be so difficult from a satellite. This means it would be even better than a base on the moon; a gateway for missions heading further into the solar system.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook and Twitter. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Dr. Ian Whiitaker is a senior lecturer in physics at Nottingham Trent University in Nottingham, England in the United Kingdom. He earned a master's of physics with space science and technology from the University of Leicester in 2006 and earned his Ph.D. in space physics from the University of Wales, Aberystwyth in 2010 while studying the interaction of the sun with the upper atmosphere of Venus. Ian has lectured at Nottingham Trent University since 2017 and has a special interest in space science outreach. In addition to his lecturing duties, Ian is a contributor to The Conversation, where he writes about a wide range of issues on space exploration and science.