NASA's Perseverance Mars rover landing: Why do we keep going back to the Red Planet?

With hundreds of worlds in the solar system to explore, it's fair to ask as NASA's Perseverance rover makes its final approach for landing Thursday (Feb. 18): Why do we keep going back to Mars?

After all, many dozens of spacecraft have visited the Red Planet since the 1960s, and a good portion made it down safely to the surface, too. We've found evidence of water, organics, methane and more — what else is there to explore, one might ask?

While the chances of ancient life on Mars appear high, the argument that we should explore the Red Planet because it's a potentially habitable world holds less weight when you remember Mars is not the only such place in our neighborhood. Scientists have tracked spurting water at Saturn's moon Enceladus and Jupiter's moon Europa, to name a few potentially habitable water-ice worlds in our solar system.

You can watch the Mars landing live here and on Space.com's homepage, courtesy of NASA, beginning at 2:15 p.m. EST (1915 GMT). The landing is expected at 3:55 p.m. EST (2055 GMT).

Related: How to watch NASA's Perseverance rover land on Mars

Perseverance rover's Mars landing: Everything you need to know

Book of Mars: $22.99 at Magazines Direct

Within 148 pages, explore the mysteries of Mars. With the latest generation of rovers, landers and orbiters heading to the Red Planet, we're discovering even more of this world's secrets than ever before. Find out about its landscape and formation, discover the truth about water on Mars and the search for life, and explore the possibility that the fourth rock from the sun may one day be our next home.

Also, last year, a highly controversial discovery of phosphine in the atmosphere of Venus spurred some claims about life on the hellish planet, although experts say that's a long stretch with the evidence we have now. More investigation will be required to figure out if the phosphine signature is spurious or persistent, and where it came from.

Nevertheless, scientists say there is something very special about Mars, so special that it in fact spurred three new missions that have recently arrived at or are currently approaching the Red Planet. Mars is close enough to Earth that it can be visited relatively easily with current technology, with the planets aligning for launch opportunities every two years or so. Its atmosphere is challenging to land and navigate, but it won't crush your spacecraft on the surface or melt it like at Venus, according to a researcher who has investigated the surfaces of both worlds.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"While we've sent spacecraft to the surface [of Venus], they don't last long at 450 degrees Celsius [842 Fahrenheit] at intense atmospheric pressures," Richard Léveillé, who researches Mars geochemistry and mineralogy at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, told Space.com.

Léveillé played a small role in the Surface and Atmosphere Geochemical Explorer (SAGE) proposal to explore Venus, a finalist NASA New Frontiers mission concept that after further study among the proposals, resulted in the OSIRIS-REx asteroid mission instead being selected in 2011.

"It was designed to last a minimum of four minutes; that was the NASA baseline for mission success," Léveillé recalled of the Venus concept. Compare that to a Mars rover mission like NASA's Opportunity rover, which was designed to last 90 days — that's days, not minutes — on the surface and finally expired due to a dust storm after nearly 15 Earth years of epic exploration.

Another thing working in Mars' favor is the accessibility of rocks on the surface that show evidence of evolution through much of the solar system's 4.5 billion years of history, Léveillé said. Venus has a very young surface of perhaps 500 million years or so, while other potentially life-friendly worlds also have seen a lot of change if water is continually spurting from the ice.

And here is where Perseverance may shine in the long-standing search for life on Mars, as it is about to land next to a delta in Jezero Crater — a place where water once flowed, similar to the rich Nile delta in Egypt today where cities have flourished for millennia. On Earth, Léveillé studies how microbes leave traces behind in rocks. In lakes and water environments, the sediment piles up and if the water leaves, the sand is left behind and hardens into rock, he explained.

"Microbes will also interact with [rock] minerals on a small scale and produce or precipitate minerals in a water environment," he added. With the right instruments, he said, scientists can look for biosignatures, or signs of past life. But therein lies the rub.

Perseverance is a powerful mission, but the small car-sized rover can only carry so many instruments and so much equipment to Mars. Perseverance thus demonstrates why it's important to keep going back to Mars, because part of its mission design is to set the most promising samples aside. Later in the decade, if planning and funding persist, NASA and the European Space Agency will start an ambitious sample-return mission to finally bring the rocks back to Earth where they can be looked at in advanced, protected facilities on our home planet.

A heritage of Mars exploration

Mars is a popular destination this month. Just days ago, both the United Arab Emirates' Hope mission and the Chinese Tianwen-1 mission arrived in orbit to start their own sets of work. Both nations, first-timers at Mars, have ambitious plans in store. Hope will act as a long-term weather station at Mars, gathering information about the atmosphere to seek patterns in weather and climate. Tianwen-1 is an orbiter-rover-lander combination that, among other things, could look for precious water reserves under the Martian surface using ground-penetrating radar on the rover.

But humanity's obsession with Mars begins with the dawn of recorded astronomy observations. The red dot in the sky stood out among the background stars and had an interesting track across the sky, visible to even early humans with no telescopes.

"We've had an ages-old fascination with Mars. It's there in the sky. It's bright red. People associate it with the god of war," Joe Cassady, executive director of space at Aerojet Rocketdyne and executive vice-president of Explore Mars, told Space.com.

A few hundred years ago, telescopes became available and by the 1800s, there were debates about possible (now disproven) canals on Mars' surface supporting a dying civilization, which spurred such science fiction tales such as H.G. Wells' "War of the Worlds" in 1898.

Even today's pictures of mountains and plains on Mars seem relatable to humans used to mountainous regions on Earth, Cassady added. "We can actually think about people getting out of their landers and walking around and going into the deep canyons and going on the top of [the perhaps dormant Mars volcano] Olympus Mons. I think from that standpoint, it feels like it's within our grasp to do that."

The first Mars spacecraft, however, suggested a dry and barren world just like the moon. NASA's Mariner series sent a few flyby missions to the Red Planet in the 1960s and by sheer lack of luck, happened to zoom past only the battered, cratered regions of the planet. Mariner 9, an orbital mission that arrived in 1971, finally showed the diversity of Mars, including a vast canyon system named Valles Marineris and a set of volcanoes high enough to poke through a global dust storm that enveloped the planet upon Mariner 9's arrival.

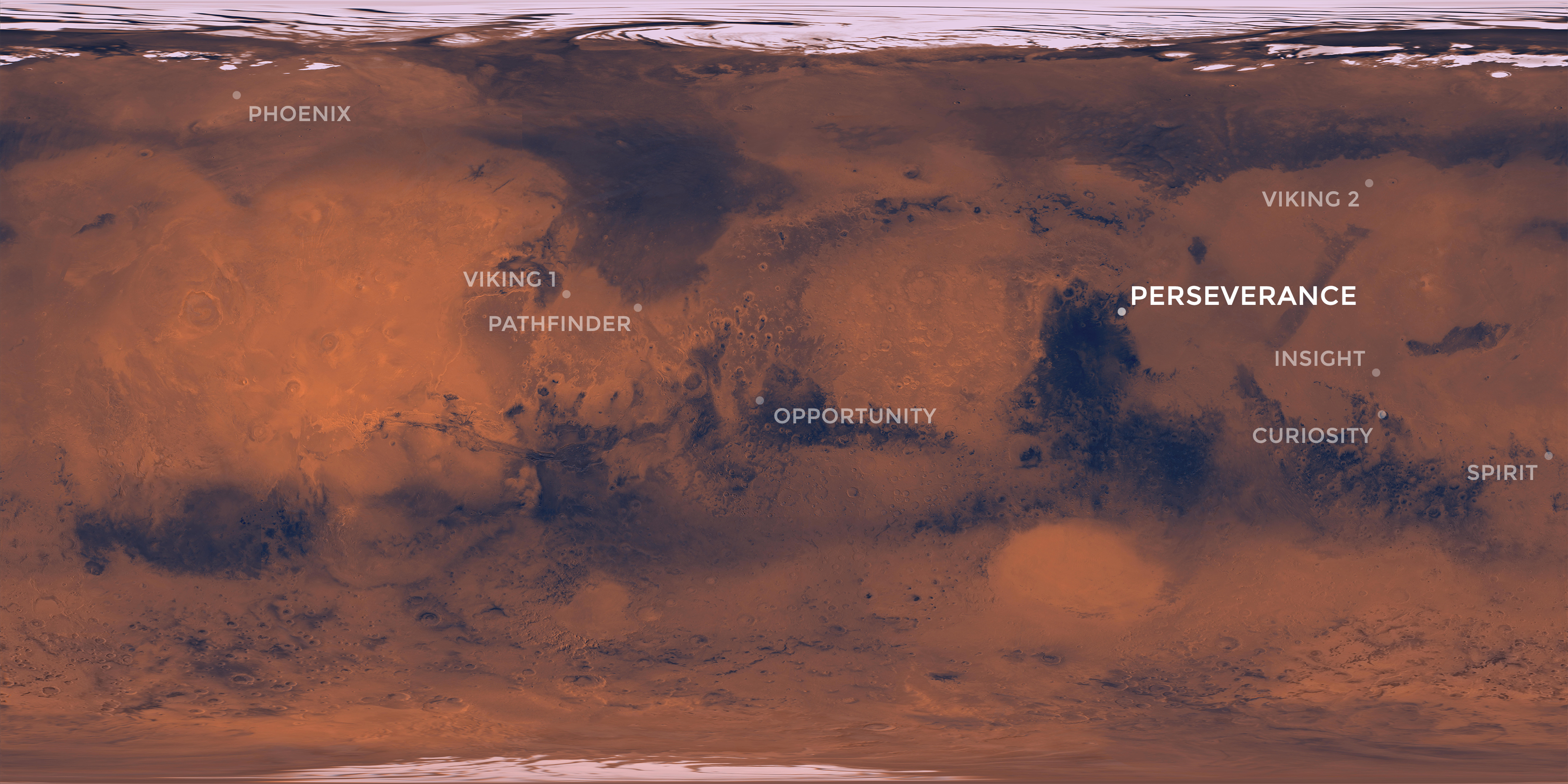

While two NASA landing missions (Vikings 1 and 2) in the 1970s and 1980s sought evidence of life and found inconclusive results, the picture emerging of Mars was a planet of change. Volcanoes and canyons imply a planet that was once quite active, and may still be. Later missions from the 1990s forward have sought evidence of water on Mars, and we've found quite a bit of evidence on the surface, in ice caps and probably underground, too.

Orbiters and landers have proliferated at Mars in recent years from multiple nations, looking at the atmosphere, the surface, marsquakes and much more. But it's the rovers — only American to date, although China's Tianwen-1 is scheduled to land in May and Europe plans to send the Rosalind Franklin rover aloft in 2022 — that have attracted the most public attention so far.

NASA's Sojourner rover was a tiny breadboxed-size rover that tested out mobility on Mars in 1997, and you can equate its tentative steps to the first test helicopter, Ingenuity, that will ride on Percy's belly to the surface. Then there were the powerful Mars Exploration Rovers Spirit and Opportunity who far outlasted their 90-day missions in 2004, and the Curiosity rover that landed in 2012 and climbed a mountain to find extensive evidence of water, organics and methane on the surface of Mars. (Curiosity is still going, too, and will be used to better put Perseverance's results into context — and vice-versa.)

Perseverance does measurably push the science of Mars forward even without taking into account the sample return portion, Cassady said. A targeting landing system using terrain-relative navigation (powered by artificial intelligence) will allow the rover to touch down in more treacherous terrain than ever before. "We're going to some place that is geologically interesting and potentially biologically interesting, but full of gullies and boulders and dangerous things," he said.

The rover will also include an experiment to test oxygen generation on the Red Planet — potentially useful to get humans on board future missions — and the Ingenuity helicopter, which could herald the arrival of drone scouts in a few decades. "We're taking along some cool technology aimed at pioneering what we'd like to do for future missions," Cassady explained.

Ultimately, Perseverance will have to demonstrate a high scientific return to continue working beyond its primary mission of at least one Martian year (or 687 Earth days). But if it succeeds, the mission may serve as a crucial turning point in Mars exploration. It could bridge the earlier findings of water, methane and organics to more firm evidence of life and habitability, and also serve as a herald for future human missions as soon as the 2030s or 2040s.

And it's all part of the plan to learn more about the Red Planet, McGill's Léveillé explained.

"NASA has a program of Mars exploration. It's not just randomly sending spacecraft; instead, the program is designed to take a stepwise approach to investigate different environments on Mars, and to characterize those environments: Are they habitable, and do they have the requirements of life."

Visit Space.com for complete coverage of the Perseverance Mars rover's landing on the Red Planet.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.