When is the Winter Solstice and what happens?

Winter Solstice has long marked a time of rebirth, behind it are fascinating astronomical events.

When is the Winter Solstice?

The next Winter Solstice for the Northern Hemisphere will occur on Dec. 21, 2025, and the next Winter Solstice for the Southern Hemisphere will occur on June 21, 2025.

The Winter Solstice, or the December Solstice, is the point at which the path of the sun in the sky is farthest south.

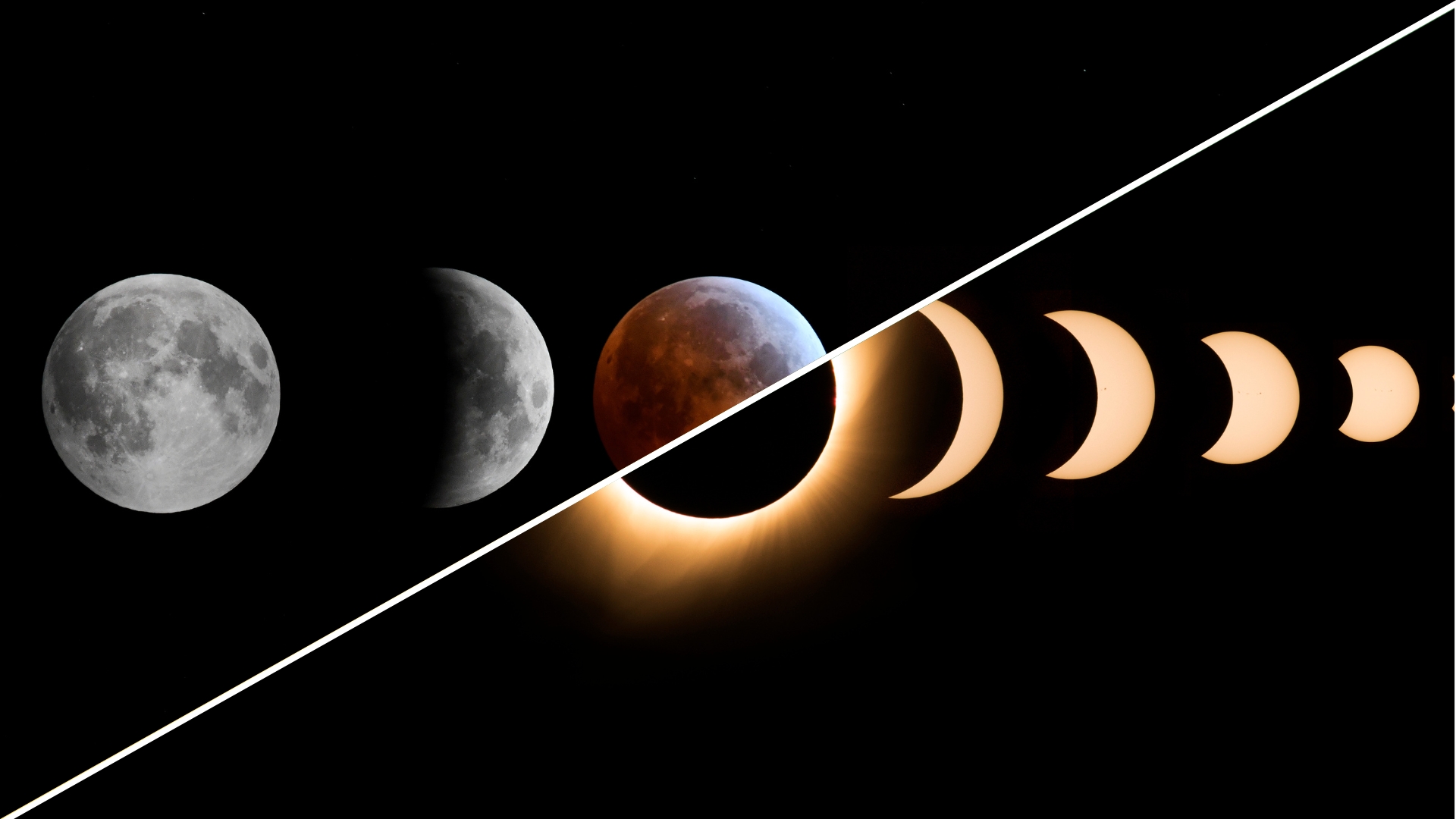

At the Winter Solstice, the sun travels the shortest path through the sky resulting in the day of the year with the least sunlight and therefore, the longest night.

In the lead-up to the Winter Solstice, the days become shorter and shorter, then on the evening of the solstice — in the Northern Hemisphere occurs annually Dec. 21 or Dec. 22 — winter begins, according to a NASA resource. From then onwards the days become increasingly long leading up to the Summer Solstice, or the June Solstice, and the longest day of the year.

What happens in the Winter Solstice?

During the day, the Northern Hemisphere will have about 7 hours and 40 minutes of daylight, marking the shortest day of the year. Earth's axis will be titled the farthest away from the sun.

To be precise, the Winter Solstice marks what is known as the "astronomical winter" — but don't worry, this doesn’t mean it will be colder than any other winter. The moniker is simply adopted to distinguish it from the meteorological winter.

While the astronomical change of seasons is related to Earth's position around the sun and its axis, the meteorological seasons are marked by the first day of a particular month. So meteorological winter proceeds astronomical winter by three weeks, occurring on Dec. 1.

Though the Winter Solstice is an annual event, Earth actually experiences two Winter Solstices each year. One in the Northern Hemisphere, and the other in the Southern Hemisphere.

Earth’s journey around the sun

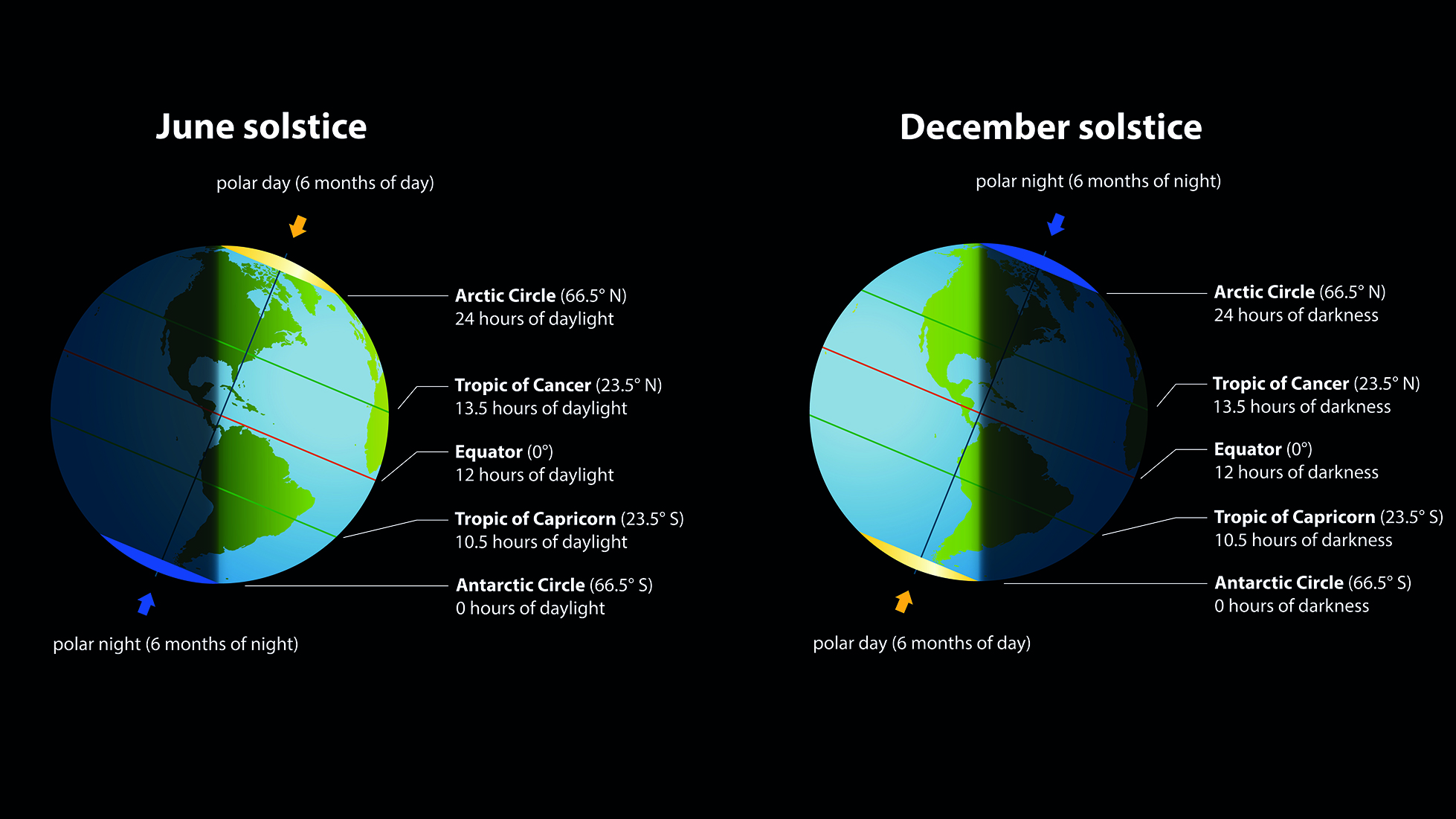

According to Britannica, Earth's axis has an around 23-degree tilt and without this, not only would our planet not have a Winter Solstice, it would not have seasons at all. The axial tilt of the Earth means that as our planet journeys around the sun different areas of the planet experience varying degrees of sunlight.

Without the axial tilt, the sun would remain directly about the Equator, and everywhere on the planet would receive the same amount of light the year through.

During the Winter Solstice, the North Pole is tilted at around 23.4 degrees away from the sun, meaning its rays move southward from the Equator.

To picture this tilt, imagine skewering the Earth on a massive pole from the Northern Hemisphere, through the center of the planet, and down to the Southern Hemisphere.

This pole represents the Earth's axis and is poking out into space from the Northern and Southern Hemispheres, according to an article published on NASA's Watch the Skies blog. During December, the part of the pole that extends from the Northern Hemisphere is pointing away from the sun.

Visualizing this pole, it quickly becomes obvious that as the Northern pole is angled away from our star, the Southern pole must be angled towards it.

That means Winter Solstice accounts for half of our planet's solstices. The other two are the Summer Solstices, and you may be unsurprised to learn that the four solstices are interconnected.

The Winter Solstice: North and South

While the Winter Solstice is occurring on Dec. 21 2024, in the Northern Hemisphere, this date will mark the Summer Solstice in the Southern Hemisphere.

Unsurprisingly, as the Southern Hemisphere experienced its Winter Solstice on June 20, the Northern Hemisphere is in the midst of its Summer Solstice.

Just as the Winter Solstice marks the point in the tilting of Earth's axis at which it points the farthest from the sun, the Summer Solstice marks the point at which our planet has its maximum axial tilt towards our star.

Think about the imaginary "Earth pole" again. If the part extending from the Northern Hemisphere is pointed away from the sun, the part of the pole extending from the Southern Hemisphere points toward our star.

During the Summer Solstice in the Northern Hemisphere, the pole that extends from this half of the planet is pointed towards the sun. Thus in the Southern Hemisphere, that pole points away.

This reflective almost mirror-image nature extends into the phenomena surrounding the opposing solstices.

The Winter Solstice marks the shortest day of the year, the Summer Solstice marks the longest period of sunlight. Following the Summer Solstice, the days become increasingly shorter, just as the days become longer after the Winter Solstice. During the Summer Solstice, the sun appears at its most northerly in the sky, the Winter Solstice, as mentioned, sees it as its most southerly.

Today we are aware of the astronomical events that lead to the solstices and their effect on the planet and we can imagine cosmic poles that impale our planet. But for our ancestors, these days had almost supernatural significance, meaning not only were they marked by both festivals and celebrations, they often birthed dark folkloric tales.

The Winter Solstice: History and folklore

The significance of the Winter Solstice to our ancestors was probably a result of the fact it marked the lengthening of days, leading to its reputation as a time of rebirth.

Because of its significance, there are simply too many Winter Solstice celebrations and festivals to list. The first that springs to the minds of many is the Christian celebration of Christmas. But, the birth of Jesus Christ was not always celebrated around the Winter Solstice. The adoption of Dec. 25 was pioneered in 336 A.D. by the Roman Emperor Constantine.

Historians speculate this was done by the Emperor as a move to weaken established pagan celebrations that occurred around the Winter Solstice. The date wouldn’t be accepted by the Eastern Empire for around another 500 years, and Christmas wouldn’t become a major Christian festival until the 9th Century.

The remnants of these overshadowed pagan traditions remain in our Christmas celebrations, for instance, and according to the free dictionary, the Scandinavian Winter Solstice festival of the Feast of Juul involved the burning of Juul logs to symbolize the returning of the sun, giving rise to the Christmas tradition of Yule Logs.

With little understanding of the Earth-sun system and what astronomical bodies were, many of our predecessor’s Winter Solstice celebrations marked ritual celebrations of the death and rebirth or even the theft and return of the sun.

One such tale is the Finnish myth that centers around Louhi, a powerful and evil witch that ruled over the mythical northern realm of Pohjola. In the myth, Louhi steals the sun and the moon away, holding them captive inside a mountain, causing the waning daylight leading up to the Winter Solstice.

Of course, the superstitious aspects of the Winter Solstice have diminished as our knowledge of the solar system and astronomy has increased. Now we use heating systems and electric lights to hold the cold and dark of winter back and give little thought to the risk of sun theft.

Yet, fortunately, some traditions remain. Festivals around the Winter Solstice still mark a time to gather and celebrate even after all of our advances and the vanquishing of superstition by science.

Additional information

Explore the difference between the equinox and solstice with the UK Met Office. Learn how to make your own solstice and equinox "suntrack" season model with NASA and the Stanford Solar Center. Discover 11 interesting June solstice facts with Time and Date.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

- Daisy DobrijevicReference Editor