This Yellow Egyptian Glass Was Forged by a Meteorite Impact 29 Million Years Ago

Visit the right patch of desert along the border of Libya and Egypt, and you could stumble on pieces of pale yellow glass, the traces of a meteorite impact that took place 29 million years ago.

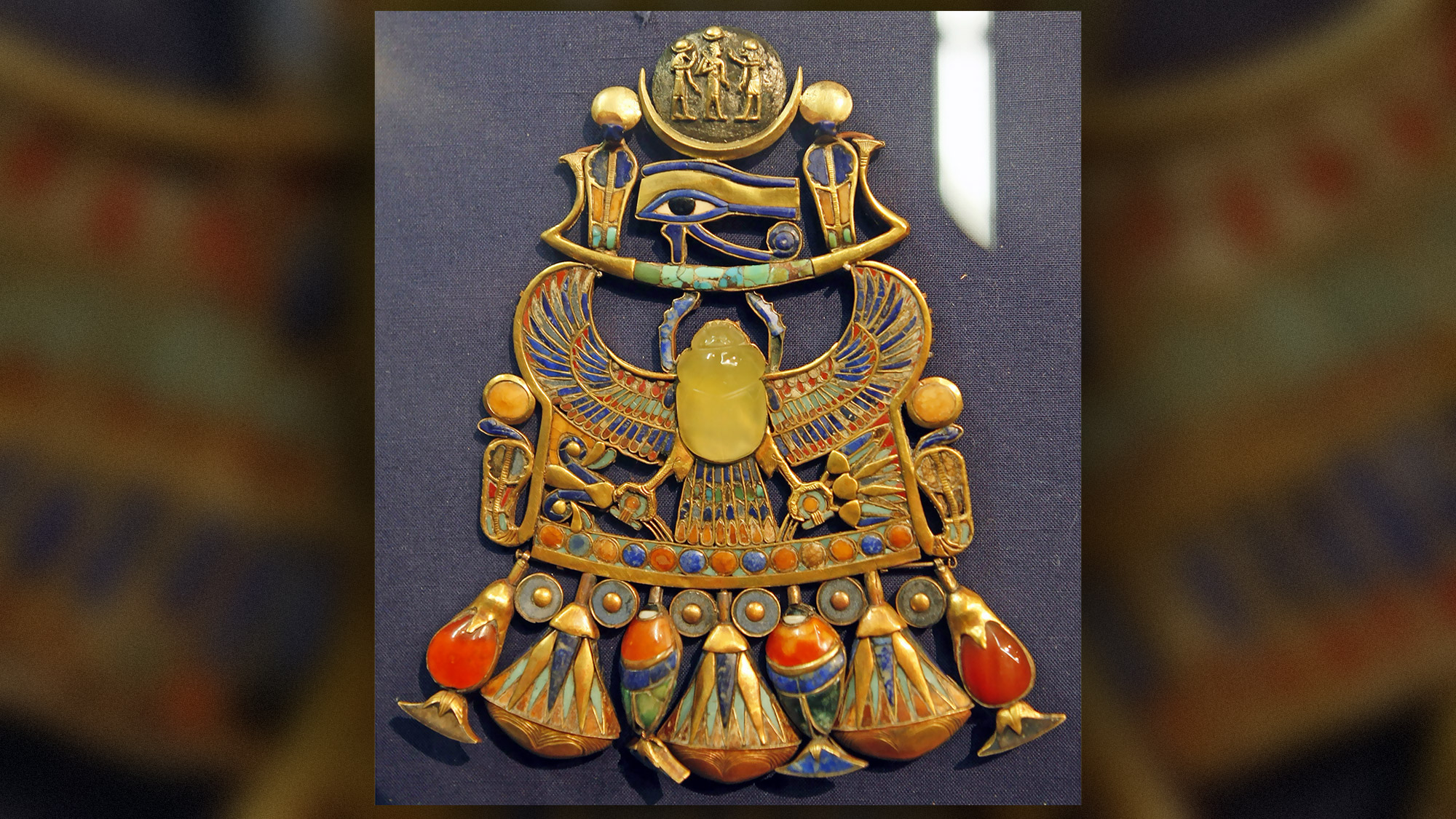

That glass, one notable piece of which was used in jewelry found in King Tut's tomb, has long been argued to have celestial roots. It's also the subject of a new study, which finds that so-called Libyan Desert Glass was likely created by a meteorite impact, not by an airburst of a space rock. If the research holds up, it suggests that scientists studying the threat of asteroids colliding with Earth may not need to worry so much about the consequences on the ground of large space rocks exploding in the atmosphere.

"Both meteorite impacts and airbursts can cause melting," lead author Aaron Cavosie, a geologist at Curtin University in Australia, said in a statement. "However, only meteorite impacts create shock waves that form high-pressure minerals, so finding evidence of former reidite confirms it was created as the result of a meteorite impact."

Related: Even If We Can Stop a Dangerous Asteroid, Being Human May Mean We Don't Succeed

They knew that whether the glassmaking space rock hit the ground or not, it was large. But Cavosie and his co-author wanted to pin down whether the culprit was an impact or an airburst. So they worked with seven pieces of the pale yellow glass, looking at them under a high-powered scanning microscope. That let the pair get a close-up look at zircon crystals within the glass, which develop slightly different structures depending on what happens to them over the millennia.

That analysis suggested some of the zircon crystals had once been reidite, a mineral that only forms under very specific high-pressure circumstances that match what occurs when a meteorite slams into Earth, but not when such a space rock explodes in the air. (In an email to Space.com, Cavosie added that although scientists haven't spotted a crater to match the impact, there's a lot of sand in the area that could be hiding such a structure below the dunes.)

Cavosie and his co-author hope that's comforting news for planetary defense experts, who focus on the threat of asteroids colliding with Earth and what humans can do to protect ourselves. That's because after the airburst over Chelyabinsk, Russia, in 2013, people had worried that Libyan Desert Glass was formed during a much, much larger airblast.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Now, the geologists say that with the reidite identified in Libyan Desert Glass, that scenario is off the table. Combine that with the fact that geologists haven't tracked down any evidence of relatively recent reidite-free glass samples, and the findings suggest that even massive airblasts don't have as serious of consequences on the ground as some people had feared.

The research is described in a paper published May 2 in the journal Geology.

- This Scientist Is Creating Fictional Asteroids to Save Humanity from Armageddon

- How Do You Stop a Hypothetical Asteroid From Hitting Earth? NASA's On It.

- Huge Asteroid Apophis Flies By Earth on Friday the 13th in 2029

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.