In a cosmic horror show, this zombie star survived a supernova explosion

The "grave" of an undead white dwarf star is marked by a cosmic funeral wreath.

Astronomers have intensely studied a zombie star lurking in the heart of supernova wreckage. Such a cosmic explosion should have destroyed this undead white dwarf star, but instead, it marked its celestial grave with a "flower" created from debris.

Now, astronomers have turned the event into a 3D movie.

Humanity first became aware of this star's death throes in 1181 when a new star, or "guest star," appeared in the constellation of Cassiopeia for six months before fading away. This actually made the supernova, now designated SN 1181, one of the few supernovas observed before the invention of the telescope. In 2021, amateur astronomer Dana Patchick tracked SN 1181 back to its location in the nebula Pa 30 that's situated within the Milky Way, determining the supernova erupted around 1,000 years ago (about 200 years before our ancestors spotted and documented it).

And recently, a team led by Tim Cunningham from the Center for Astrophysics, Harvard & Smithsonian, and Ilaria Caiazzo, assistant professor at the Institute of Science and Technology Austria (ISTA), have conducted a detailed study of the remains of SN 1181.

"Our first detailed 3D characterization of the velocity and spatial structure of a supernova remnant tells us a lot about a unique cosmic event that our ancestors observed centuries ago," Caiazzo said in a statement. "But it also raises new questions and sets new challenges for astronomers to tackle next."

Clearly, SN 1181 isn't your typical supernova, which is why it has fascinated astronomers like Cunningham and Caiazzo. This is because white dwarfs like this zombie star shouldn't have survived the cosmic horror show that birthed them.

When a star explosively returns from the dead

SN 1181 is part of a sub-class of supernova called "Type Ia supernovas." These kinda of supernovas are usually so uniform that astronomers refer to them as standard candles because it's possible to use them when measuring celestial distances. To be clear, these aren't the type of supernovas that mark the death of a star when the star runs out of fuel needed for nuclear fusion and collapses under the influence of its own gravity (leaving a black hole or neutron star in is wake).

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Instead, Type Ia supernovas begin with a dead star, one that is ravenously feeding from a stellar companion. These cosmic ghouls are white dwarfs, the kind of stellar corpse the sun will also leave behind when it dies in around 6 billion years. However, the sun's white dwarf phase will mark its peaceful rest as a cooling and fading cosmic ember — other white dwarfs may not see such tranquility.

Just like in a Hammer horror movie starring Christopher Lee, it is always some hapless bystander who pulls the stake from Dracula's chest before turning into a meal. This is the dead stars' companions that come too close.

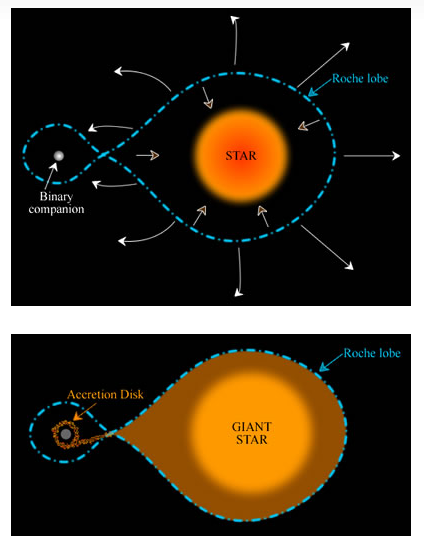

That's because when these future "donor stars" swell up in their red giant phases, (which will eventually end in them becoming white dwarfs themselves) they fill their section of the system beyond a sideways-figure-eight-shaped limit called a "Roche lobe." This results in "Roche lobe overflow," with matter flowing from this donor star to the white dwarf, causing the white dwarf to spring back to life.

However, this situation can't continue forever. Just like Lee's Dracula often did, these white dwarfs eventually get a touch too greedy.

As the white dwarf feeds from its cosmic companion, the material it strips away can't fall directly to the dead star because the material still has angular momentum. This means that material forms a swirling flattened cloud, called an accretion disk, around the white dwarf that gradually feeds it. Yet, despite a slowed delivery, this stolen stellar matter still piles up on the surface of the white dwarf, causing it to become unstable.

The situation ends with a thermonuclear explosion that completely destroys the white dwarf. But this cosmic horror story doesn't always have such a neat ending; sometimes, there is a sequel in the offing. That is because, in very rare occasions, the white dwarf star isn't completely destroyed in the supernova. Instead, it lives on as a shattered remnant, or "zombie star."

These occurrences are called "Type-Iax supernovas," and astronomers think they could account for as little as 5% of Type Ia supernovas. As you may have guessed, SN 1181 is an example of a Type-Iax supernova.

The Type-Iax supernova in the nebula Pa 30 has left this zombie star one of the hottest stellar bodies in the Milky Way, with an estimated surface temperature of around 360,000 degrees Fahrenheit (200,000 degrees Celsius). For comparison, the sun has a surface temperature of around 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit (5,500 degrees Celsius).

Additionally, this zombie star violently lashes out at the rest of its home nebula with stellar winds that reach speeds of 36 million miles per hour. That's about 45,000 times as fast as the speed of sound when measured here on Earth, or 25,000 times as fast as the top speed of a Lockheed Martin F-16 jet fighter (clearly, this undead star is not one of those traditional slow zombies, as seen roaming throughout a George Romero flick).

Such violent nature makes this shattered white dwarf an ideal candidate for the study of these rare supernovas, and that is exactly what Cunningham, Caiazz and colleagues set about doing.

Beauty emerges from horror

To conduct this investigation, the team turned to data collected by the Keck Cosmic Web Imager (KCWI). This is a spectrograph located 13,000 feet (4,000 meters) above sea level near the summit of Mauna Kea volcano, Hawaii's highest peak, at the W. M. Keck Observatory.

KCWI is capable of detecting the universe's faintest sources of light emanating from the "cosmic web," the largest structure in the cosmos where matter uses a "roadway" to arrive in clumps, forming galaxies and galaxy clusters.

The sensitivity of this instrument, which can gather a spectrum of light from every pixel it creates, allowed the team to build a 3D model of SN 1181 and visualize the motion of its wreckage. That let the team build a "movie" of this supernova debris. In previous studies, SN 1181 has appeared as a static "fireworks display."

The result was a stunning, dynamic image resembling the emerging petals of a cosmic dandelion created by filaments of matter racing out at incredible speeds. Incredibly, however, the team also found that these filaments haven't slowed since the explosion that launched them.

"The ejected material has not been slowed down, or sped up, since the explosion," Cunningham said in a statement. "Thus, from the measured velocities, looking back in time allowed us to pinpoint the explosion to almost exactly the year 1181."

Despite the incredible nature of these results, the study of SN 1181 isn't likely to draw to a close just yet. The 3D modeling has left some questions that still need to be answered. For instance, the team found that, beyond the dandelion-shaped filaments and their ballistic expansion, the overall shape of the supernova was not what was expected.

Cunningham, Caiazzo and colleagues demonstrated that the material flung away by the supernova, and sealed within the filaments, is strangely asymmetrical. This unbalanced geometry likely stems from the original explosion itself, suggesting it proceeded asymmetrically. Additionally, like shrapnel, the filaments appear to have a sharp inner edge, revealing an inner void surrounding the zombie star.

Like our delight with stories of ghouls, scientists' fascination with SN 1181 and its undead occupant seems set to continue long into the future.

The team's research was published on Thursday (Oct. 24) in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.